Scroll to:

Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of TiC–CoCrNi cermet: Behavior and microstructure formation

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-5-15

Abstract

Ceramic-metal composites (cermets) based on multicomponent phases are the newest research direction in the field of high-entropy and medium-entropy materials. Like traditional cermets, they consist of ceramic grains and a metal binder, with at least one of these phases being a high- or medium-entropy solid solution of three or more components in comparable concentrations. In this work, the possibility of producing (100 – x)TiC + xCoCrNi cermet in the range of x = 0÷60 wt. % by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) is investigated for the first time. It is shown that the size of the CoCrNi binder particles added to the powder reaction mixture significantly affects the combustion patterns and the structure formation of the material. When using large granules (~1.5 mm), the combustion rate is higher compared to the combustion of mixtures with a fine binder, while the chemical compositions and combustion temperatures are similar.The relative difference in the average combustion rate increases from 30 % to two times with an increase in the binder content from 10 to 40 wt. %. This effect occurs due to the combustion wave “slippage” between the granules and is explained by the assumption of thermal micro-heterogeneity of the reacting medium. The use of a finer CoCrNi powder (~0.2÷0.5 mm) allows obtaining homogeneous macrostructure of SHS products without large cracks and chips, and a finer-grained microstructure. In this case, the interaction of the binder with the TiC ceramic phase that is forming in the SHS wave is observed, which is expressed in the dependence of the crystal cell parameter of the carbide phase on the binder content. The results can be used to control the microstructure and phase composition of multicomponent cermets obtained by the SHS method.

Keywords

For citations:

Rogachev A.S., Bobozhanov A.R., Kochetov N.A., Kovalev D.Yu., Vadchenko S.G., Boyarchenko O.D., Kochetkov R.A. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of TiC–CoCrNi cermet: Behavior and microstructure formation. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):5-15. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-5-15

Introduction

Over the past two decades, high-entropy materials have attracted considerable attention from materials scientists worldwide due to their unique combination of mechanical, electrical, magnetic, and other properties [1–3]. High-entropy materials are generally defined as single-phase disordered solid solutions containing five or more elements in equal or near-equal atomic concentrations [1]. Such a configuration provides high configurational (mixing) entropy, which is believed to stabilize the solid solution phase [1; 2]. Although the stabilizing effect of entropy has not been strictly proven – leading to some criticism of the term “high-entropy” – it remains a convenient designation for this new class of materials [1; 3]. The term distinguishes them from conventional multicomponent alloys, which are typically based on one or two principal elements, with the rest acting as minor alloying additions. Recent studies have revealed that alloys containing three or four principal elements (for example, CoCrFeNi or CoCrNi) can exhibit mechanical properties superior to those of five-component or more complex systems [4; 5]. Such compositions, which follow the same design principle as high-entropy materials – namely, comparable atomic concentrations of several elements in a single phase – but contain only three to four elements, are referred to as medium-entropy alloys (MEAs). Among these, the CoCrNi alloy has attracted special interest because it possesses the highest cryogenic impact toughness among all known materials [5–7]. At room temperature, its ultimate tensile strength reaches 1000 MPa with an elongation at fracture of 70 %, and the crack-initiation fracture toughness (KJ1c ) exceeds 200 MPa·m1/2. At cryogenic temperatures, the mechanical performance further improves, with tensile strength exceeding 1.3 GPa, elongation of 90 %, and KJ1c = 275 MPa·m1/2 [5].

Cermets (powder composite materials) based on multicomponent phases have recently emerged as a novel subclass within the family of high-entropy materials. Similar to conventional cermets, they consist of ceramic grains embedded in a metallic binder; however, in these systems, either the ceramic phase, the metallic binder, or both microstructural constituents can be high- or medium-entropy solid solutions. An example of the first approach is the (Ti0.2Zr0.2Nb0.2Ta0.2Mo0.2)C0.8–Co, cermet, where the ceramic phase represents a high-entropy carbide – an equimolar solid solution of five transition-metal carbides [8]. The single-component metallic binder (Co), introduced in amounts of 7.7–15.0 vol. %, increased the fracture toughness (K1c ) up to 5.35 MPa·m1/2 while maintaining high hardness (21.05 ± 0.72 GPa), making this material suitable for cutting tool applications. The influence of different metallic binders (Co, Ni, FeNi) on the properties of (Ta,Nb,Ti,V,W)C-based cermets has also been investigated, demonstrating that these materials can compete with WC-based cemented carbides in performance [9].

An example of the second approach is the SHS-derived TiC–CoCrFeNiMe cermet, where Me = Mn, Ti, or Al [10]. The content of the ductile high-entropy binder phase reached up to 50 wt. %1, while hardness varied from 10 to 17 GPa. Using powder metallurgy techniques, other cermets with high-entropy alloy binders have been produced, such as WC–CoCrFeNiMn [11], Ti(C,N)–CoCrFeNiAl [12; 13], TiB2–CoCrFeNiTiAl [14; 15], TiB2–CoCrFeNiAl [16], TiB2–TiC–CoCrFeNiTiAl [17] and other. Such materials are now recognized as a new class of cermets [18].

Finally, according to the third approach, a material of the composition (TiTaNbZr)C–TiTaNbZr as been obtained, in which both the ceramic phase (carbide) and the metallic binder are multicomponent. This material exhibits an excellent combination of mechanical properties, including a room-temperature flexural strength of 541 MPa, a compressive strength of 275 MPa at 1300 °C, and a fracture toughness of 6.93 MPa·m1/2 [19].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the feasibility of synthesizing TiC–CoCrNi cermet by the self-propagating high-temperature synthesis method.

Materials and methods

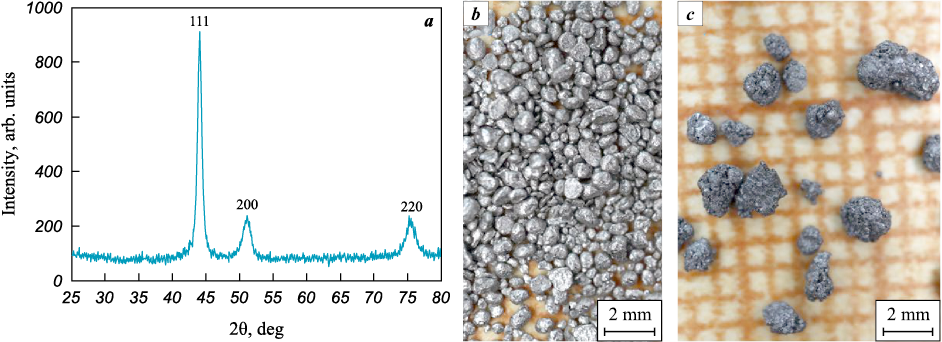

Powder mixtures of the composition (100 – x)(Ti + C) + x(CoCrNi) with different binder contents (x = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 %) were prepared for the study. The following commercial powders were used: titanium grade PTM-1 (mean particle size d = 55 µm), carbon black P-804 (d = 1–2 µm), nickel NPE-1 (d = 150 µm), cobalt PK-1u (d < 71 µm), and chromium PKh-1M (d < 125 µm). The binder phase was introduced in the form of a CoCrNi alloy powder. To produce the alloy, an equiatomic mixture of powders (34.7 % Co + 30.7 % Cr + 34.6 % Ni) was loaded into steel vials of an Activator-2S planetary ball mill (Russia) together with steel grinding balls (6 mm in diameter) in a mass ratio of 20:1 (200 g of balls per 10 g of mixture). The vials were hermetically sealed and equipped with valves for vacuum pumping and gas filling. After evacuation to a residual pressure of 0.01 Pa, the vials were filled with argon to 0.6 MPa. Mechanical alloying was carried out for 60 min at a rotation speed of 694 rpm in an argon atmosphere with a rotational speed ratio between the vial and the supporting disk of K = 2. As a result of mechanical alloying, a single-phase face-centered cubic (FCC) CoCrNi alloy powder was obtained (Fig. 1, a) with a lattice parameter of a = 3.5697 ± 0.0017 Å. Its appearance is shown in Fig. 1, b.

Fig. 1. X-ray diffraction pattern of the CoCrNi powder after mechanical alloying (a), |

The medium-entropy alloy powder was granulated by mixing it with a liquid binding agent – 4 % solution of polyvinyl butyral (PVB) in ethanol. The resulting paste was forced through a laboratory sieve with 1.6 mm mesh openings, dried in air for 10–12 h, and then sieved using a vibrating screen. Two fractions of granulated powder were used in the experiments. The coarse fraction (0.6–1.6 mm) was used as obtained (Fig. 1, c), while the fine fraction (<0.6 mm) was additionally ground in a mortar until its morphology matched that of the powder obtained directly after mechanical alloying (Fig. 1, b). This procedure provided two powders with markedly different particle sizes but identical phase composition (CoCrNi) and gasifying additive content (0.6–0.7 % PVB).

The reactive mixtures were prepared by mechanical mixing of Ti, C, and CoCrNi powders (fine or coarse fraction) without grinding to preserve the granule size. Cylindrical compacts (height 1.4–1.8 cm, diameter 1 cm, mass 2.5–4.0 g, porosity 40–45 %) were produced by double-sided cold pressing in detachable steel dies under a pressure of 120 kg/cm2.

Combustion was performed in a constant-pressure chamber under argon atmosphere at P = 1 atm. The compact was placed on a boron nitride (BN) ceramic support and fixed on top with a BN ring to prevent elongation during combustion. The SHS process was initiated at the upper surface of the compact using a heated tungsten coil through an ignition pellet of Ti + 2B composition to ensure stable ignition conditions. The process was recorded on video through a viewing window, and the average linear combustion velocity was determined frame-by-frame. The combustion temperature (Тc ) was measured with a W-Re thermocouple (WR5/WR20) with a junction diameter of 0.2 mm, inserted 5 mm deep along the axis from the bottom of the compact.

Phase composition and crystal structure were analyzed using a DRON-3M X-ray diffractometer (Burevestnik, Russia). Microstructural observations were performed on an Ultra+ scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) in secondary- and backscattered-electron modes.

Results

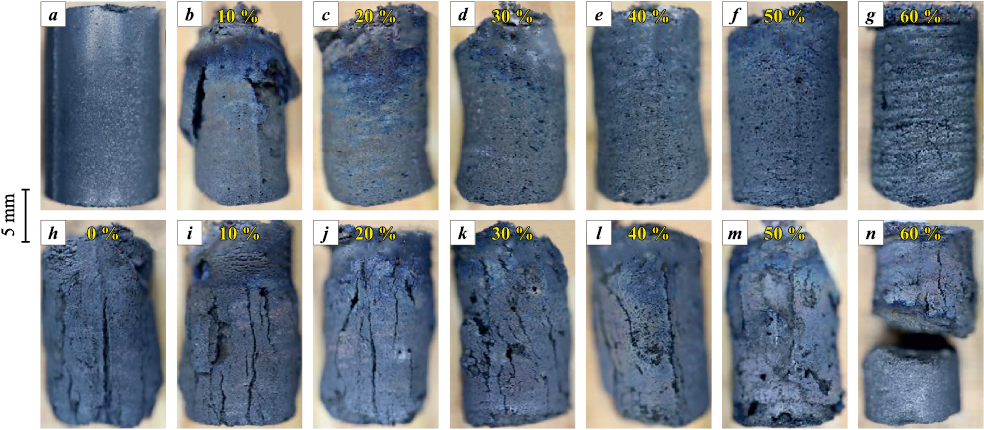

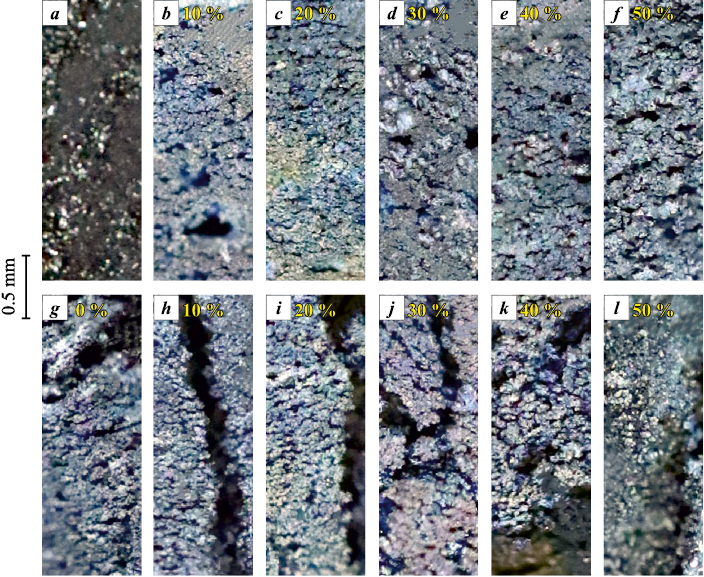

Fig. 2 shows the TiC samples before and after SHS. Samples produced from mixtures containing the fine CoCrNi powder binder underwent slight deformation during combustion but retained relatively homogeneous surface morphology (Fig. 2, b–g). The only exception was the sample with 10 % binder, which exhibited large surface cavities. A spiral pattern characteristic of the so-called spin combustion mode [20] appeared on the sample containing 60 % binder [20]. In contrast, all samples with coarse granulated binder powder exhibited severe cracking, with large cavities and cracks up to several millimeters long oriented along the compact axis (Fig. 2, i–n). The sample containing 60 % coarse binder burned only halfway and the reaction ceased. The differences in surface macrostructure became more evident at higher magnification (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Photographs of TiC samples before (a) and after SHS (b–n): TiC without binder (h);

Fig. 3. Surface morphology of TiC samples before (a) and after SHS (b–l): |

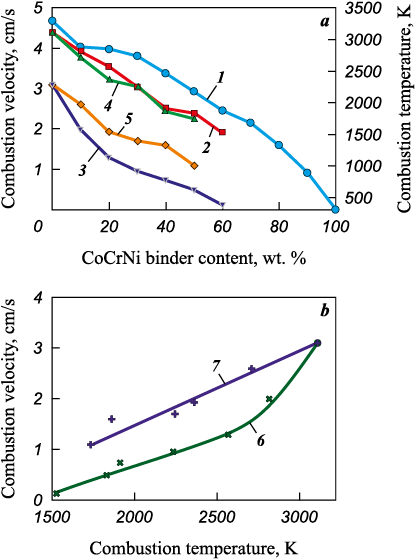

The dependences of the average linear combustion velocity on the binder content (Fig. 4, a) were markedly different for the fine and coarse CoCrNi powders. Compositions containing coarse granules burned significantly faster, with the relative difference in mean combustion velocity increasing from 30 to 100 % as the binder content increased from 10 to 40 %. The experimentally measured maximum temperature of the combustion products depended on the binder content but was nearly independent of the initial binder particle size introduced into the reactive mixture prior to combustion. This temperature was slightly below the calculated adiabatic value, which can be ascribed to heat losses from the compact to the fixture and the chamber environment, given the small specimen size. The combustion limit with respect to the concentration of the thermally inert binder was 50 % for the coarse granules and 60 % for the finer powder; beyond these levels, the reaction either extinguished or failed be initiated. The dependences of combustion velocity on maximum temperature deviated significantly from the theoretically predicted exponential behavior (Fig. 4, b). A formal estimation of the apparent activation energy from the logarithmic velocity–inverse temperature relation yielded Ea = 106 ± 14 kJ/mol for the fine CoCrNi powder and 23 ± 8 kJ/mol for the coarse powder.

Fig. 4. Dependences of combustion velocity and temperature on binder content (a) |

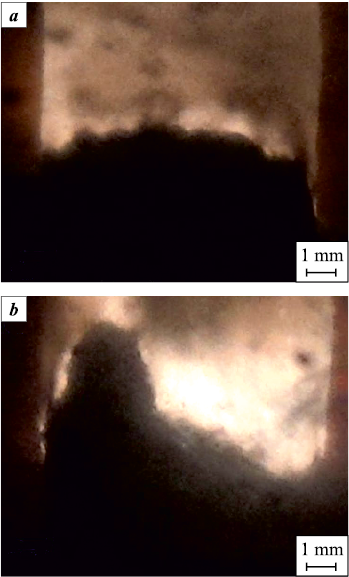

The combustion front in mixtures containing the coarsely dispersed binder powder exhibited a more curved shape compared with that in mixtures containing the fine binder (Fig. 5). However, it should be noted that front distortions and bright localized reaction zones were observed in all compositions.

Fig. 5. Video frames of the combustion front for mixtures |

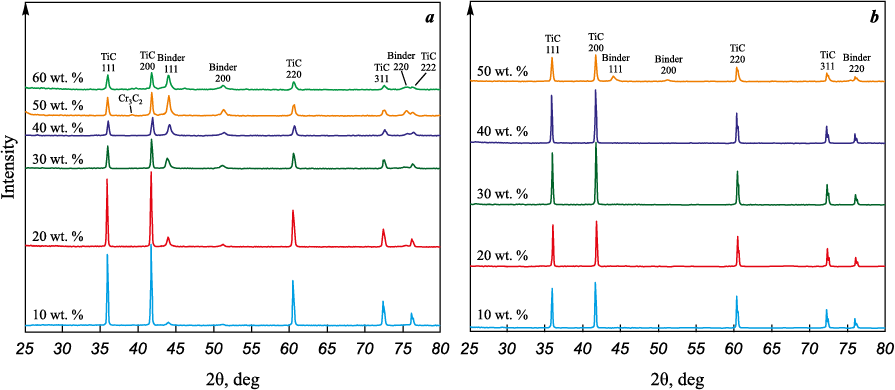

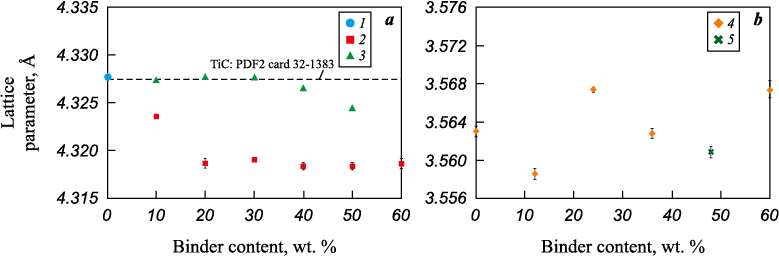

X-ray diffraction analysis of the combustion products revealed two main phases: titanium carbide (FCC) and a solid solution with FCC structure corresponding to the metallic binder (Fig. 6). In samples synthesized from mixtures with fine CoCrNi powder, the relative intensity of the binder peaks increased monotonically with binder content. At high binder concentrations, weak reflections corresponding to a third phase – presumably chromium carbide – were detected in the samples (Fig. 6, a). In samples prepared with coarse granules, the diffraction results varied greatly: some showed almost no binder reflections, while others exhibited strong peaks from this phase. Unexpectedly, the lattice parameter of the titanium carbide phase was found to depend on the particle size of the CoCrNi powder added to the mixture (fine or coarse) (Fig. 7, a). This clearly indicates an interaction between the metallic binder and the ceramic TiC phase during SHS. For the metallic phase itself, despite some scatter, no significant dependence of lattice parameter on binder content was observed (Fig. 7, b).

Fig. 6. X-ray diffraction patterns of SHS products with different binder

Fig. 7. Dependence of lattice parameters on binder content for titanium carbide (a) |

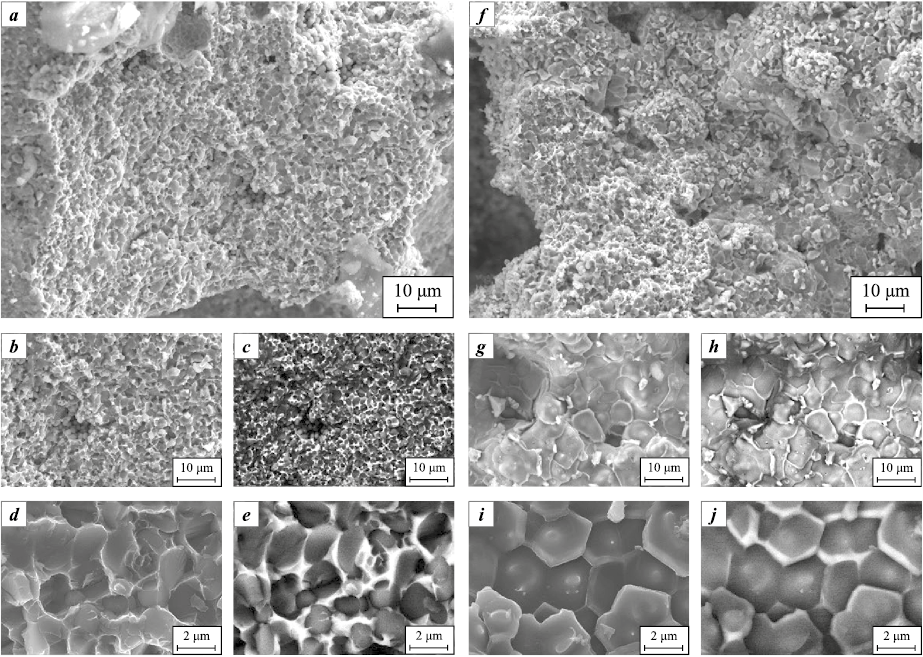

Microstructures of the synthesized cermets (fracture surfaces) are shown in Fig. 8 for the composition 60 % TiC + 40 % CoCrNi. Samples produced using fine medium-entropy alloy powder consisted of TiC grains 2–3 µm in size. The intergranular regions were filled with the binder phase (appearing bright in backscattered electron images, while TiC grains appeared dark due to atomic number contrast). Overall, these samples exhibited a uniform structure. In contrast, samples obtained using coarse granules contained areas with strongly varying TiC grain sizes: along with fine-grained regions, isolated areas with coarser grains (5–10 µm) were observed. The binder layers in these regions were thinner – the larger the TiC grains, the thinner the metallic binder layers, and in some cases, they were nearly absent. Since the compositions of both cermets were identical, the observed microstructural differences evidently arise from distinct combustion dynamics and structure formation mechanisms occurring behind the combustion front.

Fig. 8. Microstructures of cermets produced by SHS from reactive mixtures |

Discussion

All experimental results obtained in this study can be explained by assuming thermal micro-inhomogeneity of the reacting medium under SHS conditions. This medium consists of the exothermic Ti + C mixture and the thermally inert diluent – the CoCrNi binder. The dependence of the combustion behavior on the particle size of the inert diluent was theoretically predicted in [21] and experimentally confirmed in [22]. The explanation of these dependencies can be summarized as follows. Fine diluent particles are completely heated within the combustion wave (in both the preheating and reaction zones) and therefore exert a strong influence on the propagation velocity of the wave. In this case, combustion proceeds under thermal homogenization conditions. In contrast, coarse diluent particles do not fully heat up within the combustion wave and thus exert a relatively weak effect on the reaction zone. The combustion wave propagates between the large particles, practically “ignoring” their presence, and the average combustion velocity in such systems is therefore higher. For example, in [22] the combustion of a Ti + C mixture diluted with chemically inert TiC particles (50 μm to 2.5 mm) was investigated. For the composition 70 % (Ti + C) + 30 % TiC, two distinct combustion modes were observed depending on the TiC particle size: at d < 240 μm the combustion velocity was 0.75 cm/s, then it increased and reached a new constant value of 2.4 cm/s for d > 750–800 μm. The dependencies obtained in the present study (Fig. 4) are consistent with these results. The main difference is that in our case, the diluent particles melt within the combustion wave and can infiltrate the pores between the TiC grains.

The effect of granulation on the combustion velocity of Ti + C and (Ti + C) + 20 % Cu compositions was studied in [23]. It was shown that the combustion velocity of granulated mixtures with a granule size of 0.6 mm was higher than that of ungranulated powder mixtures, and mixtures with 1.7 mm granules burned even faster. The explanation proposed in [23] was that impurity gases slow down combustion-front propagation. In the present work, however, only the inert diluent – not the entire reactive mixture – was granulated. Therefore, the increased combustion velocity in mixtures with coarse-grained diluent is more accurately explained in terms of the thermal micro-inhomogeneity model proposed in [21; 22]. It should also be noted that, in our experiments, the addition of the inert diluent led to a monotonic decrease in both combustion temperature and velocity (Fig. 4), in contrast to [23], where introducing 20 % Cu increased the combustion velocity relative to the undiluted Ti + C mixture.

Melting of particles and spreading of the resulting melts largely determine the macro- and microstructure of SHS products. Elongation of compacts and the formation of macroscopic cracks during combustion occur under the pressure of impurity gases – mainly hydrogen – released even in the combustion of nominally gas-free systems such as Ti + C [24–26]. Surface-tension (capillary) forces can counterbalance the gas pressure; in this case, the sample does not expand or crack, and in some cases may even shrink after SHS. During combustion of the Ti + C mixture, only titanium melts; the melt exists in a narrow region at the combustion front and is rapidly consumed in the reaction, forming solid TiC grains [26]. The expansion of the solid product leads to cracking (Figs. 2, h and 3, g). When fine metallic binder powder is added, it also melts in the combustion front, but the melt persists behind the front long enough for impurity gases to escape through fine pores. As a result, no cracking occurs (Figs. 2, b–e and 3, b–e). When the binder is added as coarse granules, however, they do not have time to melt and spread in the combustion zone, so the combustion wave propagates mainly through the Ti + C composition between the granules, leading to the formation of cracks (Figs. 2, i–n and 3, i–m).

The dependence of the microstructure and crystal structure of the SHS products on the particle size of the diluent is also related to the melting and spreading behavior of the metallic components. In cermet systems, the TiC grain size is determined by rapid growth behind the combustion wave, i.e., in the secondary structure-formation zone [27–29]. In the undiluted Ti + C system, TiC grains grow faster than in Ti + C + metal-binder systems, since carbon diffusion in liquid Ti is faster than in Ti–Ni or similar melts (see, e.g., [27], Fig. 2.20, p. 80). Because the melting of coarse binder granules proceeds slowly, some regions between them allow the Ti + C composition to react and form relatively coarse TiC grains before the CoCrNi melt penetrates these regions. These coarse-grained areas are visible in the microstructure of the products synthesized from mixtures containing coarse binder granules (Figs. 8, e–k).

The TiC grains formed in these regions interact weakly with the binder; therefore, the lattice parameter of TiC remains nearly constant (4.3276 ± 0.0008 Å) when up to 30–40 % of coarse binder granules are added, being close to that of TiC synthesized without binder. When the binder is introduced as fine particles that melt directly in the reaction zone, the nucleation and growth of carbide grains occur in the Ti–Co–Cr–Ni molten bath. This results not only in a finer microstructure (Figs. 8, a–d) but also in the formation of a (Ti,Cr)C solid solution with a modified lattice parameter (Fig. 7, a). In addition, part of the carbon may react with chromium (see traces of Cr3C2 in Fig. 6, a), which decreases the carbon concentration in the main carbide phase and correspondingly reduces its lattice parameterсновной карбидной фазе и соответствующему уменьшению параметра ячейки этой фазы.

Conclusion

The combustion and microstructure-formation behavior of (100 – x)TiC + xCoCrNi cermets (x = 0–60 %) synthesized by the self-propagating high-temperature synthesis method were investigated for the first time. It was demonstrated that the particle size of the CoCrNi binder strongly affects both the combustion process and the resulting structure. When coarse granules (~1.5 mm) were used, the combustion velocity was higher due to the “slip” of the combustion wave between the granules, and the ceramic grains were larger as a result of faster growth behind the combustion front.

The use of fine powder (~0.2–0.5 mm) produced SHS products with a more uniform macrostructure free of large cracks and chips, and with a finer microstructure. Interaction between the binder and the ceramic TiC phase formed in the SHS wave was observed. The experimentally observed regularities were explained in terms of the thermal micro-inhomogeneity of the reacting medium. The results obtained can be used to control the microstructure and phase composition of multicomponent cermets synthesized by the SHS method.

References

1. Miracle D.B., Senkov O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Materialia. 2017;122:448–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2016.08.081

2. Zhang Y. High-entropy materials. A brief introduction. Singapore: Springer Nature, 2019. 159 p. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8526-1

3. Cantor B. Multicomponent high-entropy Cantor alloys. Progress in Materials Science. 2021;120:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100754

4. Gali A., George E.P. Tensile properties of high- and medium-entropy alloys. Intermetallics. 2013;39:74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intermet.2013.03.018

5. Gludovatz B., Hohenwarter A., Thurston K.V.S., Bei H., Wu Z., George E.P., Ritchie R.O. Exceptional damage-tolerance of a medium-entropy alloy CrCoNi at cryogenic temperatures, nature. Communications. 2016;7:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10602

6. Laplanche G., Kostka A., Reinhart C., Hunfeld J., Eggeler G., George E. Reasons for the superior mechanical properties of mediumentropy CrCoNi compared to high-entropy CrMnFeCoNi. Acta Materialia. 2017;128:292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2017.02.036

7. Xu D., Wang M., Li T., Wei X., Lu Y. A critical review of the mechanical properties of CoCrNi-based medium-entropy alloys. Microstructures. 2022;2:1–32. https://doi.org/10.20517/microstructures.2021.10

8. Luo S.-C., Guo W.-M., Lin H.-T. High-entropy carbide-based ceramic cutting tools. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2023;106:933–940. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.18852

9. Potschke J., Vornberger A., Gestrich T., Berger L.-M., Michaelis A. Influence of different binder metals in high entropy carbide based hardmetals. Powder Metallurgy. 2022;65(5):373–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325899.2022.2076311

10. Rogachev A.S., Vadchenko S.G., Kochetov N.A., Kovalev D.Yu., Kovalev I.D., Shchukin A.S., Gryadunov A.N., Baras F., Politano O. Combustion synthesis of TiC-based ceramic-metal composites with high entropy alloy binder. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2020;40(7):2527–2532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.11.059

11. Velo I.L., Gotor F.J., Alcala M.D., Real C., Cordoba J.M. Fabrication and characterization of WC-HEA cemented carbide based on the CoCrFeNiMn high entropy alloy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2018;746:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.02.292

12. Zhu G., Liu Y., Ye J., Fabrication and properties of Ti(C,N)-based cermets with multi-component AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys binder. Materials Letters. 2013;113:80–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2013.08.087

13. Zhu G., Liu Y., Ye J. Early high-temperature oxidation behavior of Ti(C,N)-based cermets with multi-component AlCoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy binder. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2014; 44:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.01.005

14. Ji W., Zhang J., Wang W., Wang H., Zhang F., Wang Y., Fu Zh. Fabrication and properties of TiB2-based cermets by spark plasma sintering with CoCrFeNiTiAl high-entropy alloy as sintering aid. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2015;35(3):879–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.10.024

15. Fu Zh., Koc R.. Ultrafine TiB2–TiNiFeCrCoAl high-entropy alloy composite with enhanced mechanical properties. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2017;702: 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2017.07.008

16. Zhang Sh., Sun Y., Ke B., Li Y., Ji W., Wang W., Fu Z. Preparation and characterization of TiB2–(Supra-Nano-Dual-Phase) high-entropy alloy cermet by spark plasma sintering. Metals. 2018;58:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/met8010058

17. Fu Z., Koc R.. TiNiFeCrCoAl high-entropy alloys as novel metallic binders for TiB2–TiC based composites. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2018;735:302–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2018.08.058

18. A.G. de la Obra, Aviles M.A., Torres Y., Chicardi E., Gotor F.J. A new family of cermets: Chemically complex but microstructurally simple. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2017; 63:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2016.04.011

19. Chen X., Wang F., Zhang X., Hu S., Liu X., Humphry-Baker S., Gao M. C., He L., Lu Y., Cui B. Novel refractory high-entropy metal-ceramic composites with superior mechanical properties. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2024;119:106524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2023.106524

20. Maksimov Yu.M., Pak A.T., Lavrenchuk N.V., Naiborodenko Yu.S., Merzhanov A.G. Spin combustion of gasless systems. Fizika goreniya i vzryva. 1979;15:156–159. (In Russ.).

21. Shkadinsky K.G., Krishenik P.M. Stationary combustion front in a mixture of fuel and inert. Fizika goreniya i vzryva. 1985;21(2):52–57. (In Russ.).

22. Maslov V.M., Voyuev S.I., Borovinskaya I.P., Merzhanov A.G. On the role of dispersion of inert diluents in gasless combustion processes. Fizika goreniya i vzryva. 1990;26(4):74–80. (In Russ.).

23. Seplyarsky B.S., Kochetkov R.A., Lisina T.G., Vasiliev D.S. Reason for the Increasing Burning Rate of a Ti + C Powder Mixture Diluted with Copper. Combustion, Explosion, and Shock Waves. 2023;59(3):344–352. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0010508223030097

24. Merzhanov A.G., Rogachev A.S., Umarov L.M., Kiryakov N.V. Experimental study of the gas phase formed in the processes of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Fizika goreniya i vzryva. 1997;33(4):55–64. (In Russ.).

25. Mukasyan A.S., Rogachev A.S., Varma A. Microscopic mechanisms of pulsating combustion in gasless systems. AIChE Journal. 1999;45(12):2580–2585. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690451214

26. Kamynina O.K., Rogachev A.S., Umarov L.M. Deformation dynamics of a reactive medium during gasless combustion. Combustion, Explosion and Shock Waves. 2003;39(5):548–551. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026161818701

27. Levashov E.A., Rogachev A.S., Kurbatkina V.V., Maksimov Yu.M., Yukhvid V.I. Advanced materials and technologies of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis: Study guide. Moscow: MISIS, 2011. 378 p. (In Russ.).

28. Rogachev A.S., Mukasyan A.S. Combustion for the synthesis of materials: introduction to structural macrokinetics (monograph). Moscow: Fizmatlit, 2012. 398 p. (In Russ.).

29. Borovinskaya I.P., Gromov A.A., Levashov E.A., Maksimov Yu.M., Mukasyan A.S., Rogachev A.S. (eds.). Concise encyclopedia of SHS. Netherlands, Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2017. 438 p.

About the Authors

A. S. RogachevRussian Federation

Alexander S. Rogachev – Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Professor, Chief Researcher, Laboratory of Microheterogeneous Process Dynamics

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

A. R. Bobozhanov

Russian Federation

Anis R. Bobozhanov – Postgraduate Student, Junior Researcher, Laboratory of Microheterogeneous Process Dynamics

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

N. A. Kochetov

Russian Federation

Nikolai A. Kochetov – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher, Laboratory of Microheterogeneous Process Dynamics

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

D. Yu. Kovalev

Russian Federation

Dmitry Yu. Kovalev – Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Chief Researcher, Laboratory of X-ray Structural Studies

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

S. G. Vadchenko

Russian Federation

Sergey G. Vadchenko – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Leading Researcher, Laboratory of Microheterogeneous Process Dynamics

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

O. D. Boyarchenko

Russian Federation

Olga D. Boyarchenko – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Researcher, Laboratory of Physical Materials Science

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

R. A. Kochetkov

Russian Federation

Roman A. Kochetkov – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher, Laboratory of Combustion of Disperse Systems

8 Academician Osipyan Str., Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia

Review

For citations:

Rogachev A.S., Bobozhanov A.R., Kochetov N.A., Kovalev D.Yu., Vadchenko S.G., Boyarchenko O.D., Kochetkov R.A. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of TiC–CoCrNi cermet: Behavior and microstructure formation. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):5-15. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-5-15