Scroll to:

Effect of Si, Al, Cu, Cr, and TiSi2 on the formation of the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase during self-propagating high-temperature synthesis in air

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-27-35

Abstract

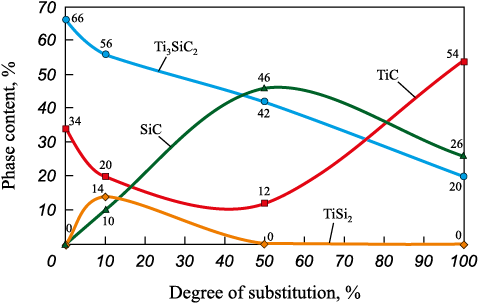

This study examines how additions of Si, Al, Cu, and Cr powders to the stoichiometric 3Ti–Si–2C (at. %) charge influence the formation of the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase during self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) performed in air within a sand bed, without a sealed reactor or controlled atmosphere. The effect of partially or fully substituting elemental Ti and Si powders with TiSi2 on the Ti3SiC2 yield is also assessed. Microstructural characterization of the SHS products was conducted using scanning electron microscopy equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy, and the phase composition was quantified by X-ray diffraction. An addition of 0.1 mol Si to the stoichiometric mixture increases the Ti3SiC2 content in the product to approximately 70 vol. %. Incorporating 0.1 mol Al decreases the Ti3SiC2 fraction to 39 vol. % and results in the formation of TiAl. In contrast, combining a silicon excess with 0.1 mol Al in the 3Ti–1.25Si–2C + 0.1Al system markedly enhances the Ti3SiC2 yield, reaching ~89 vol. %. For synthesis in the TiSi2–C system, the share of the MAX phase decreases while secondary phases become more prevalent; the maximum Ti3SiC2 content in this system is 56 vol. %. When TiSi2 fully replaces elemental silicon in the 2.5Ti–0.5TiSi2–2C mixture, the Ti3SiC2 fraction drops to 20 vol. %.

Keywords

For citations:

Umerov E.R., Kadyamov S.A., Davydov D.M., Latukhin E.I., Amosov A.P. Effect of Si, Al, Cu, Cr, and TiSi2 on the formation of the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase during self-propagating high-temperature synthesis in air. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):27-35. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-27-35

Introduction

The Ti3SiC2 MAX phase is a promising layered ternary carbide that combines key ceramic and metallic properties, including excellent oxidation resistance, high thermal and electrical conductivity, thermal-shock resistance, high-temperature plasticity, creep resistance, low density, and good machinability [1; 2]. These properties make Ti3SiC2 a potential alternative to conventional ceramics.

Many published synthesis approaches require expensive equipment, long high-temperature dwell times, and protective atmospheres, all of which increase the cost and complexity of MAX-phase production [3–6]. In contrast, the highly exothermic and economically efficient process of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) significantly simplifies the fabrication route, requires no special hardware, and proceeds much faster than furnace sintering [7; 8]. A simple method for producing MAX-phase cermets was recently proposed, based on infiltrating molten metals into a porous Ti3SiC2 skeleton synthesized via SHS in air [9]. During Ti3SiC2 formation, the reaction temperature may reach 2260 °C [10], while the maximum adiabatic combustion temperature is reported to be 2735 °C [11].

Formation of Ti3SiC2 proceeds through several stages. Initially, TiC particles and a Ti–Si melt form simultaneously. At the next stage, TiC dissolves into the Ti–Si liquid, followed by crystallization of Ti3SiC2 platelets [12–14]. Because SHS evolves extremely rapidly – values below 3–4 s are typical for the first stage – post-ignition control of the process is practically impossible. Therefore, establishing optimal synthesis parameters is essential to maximize the purity of the final Ti3SiC2 product. Deviations from charge stoichiometry and insufficient high-temperature dwell associated with fast post-reaction cooling commonly lead to increased fractions of secondary phases such as TiC and TiSi2 .

The reactions leading to TiC and the Ti–Si melt compete for the available titanium, as both intermediates form simultaneously within a single reactive system. Consequently, a deficiency of one intermediate and the excess of the other inevitably decreases the Ti3SiC2 yield in the SHS product.

TiC is frequently reported as the primary secondary phase in Ti3SiC2 synthesis, indicating an insufficient amount of Ti–Si melt available for MAX-phase platelet growth. Therefore, many studies [15–22] use chemical precursors instead of elemental Ti and Si powders. One such precursor is titanium disilicide (TiSi2 ), which has the lowest crystallization temperature among Ti–Si compounds (1330 °C).

The Ti–Si melt crystallizes within the 1480–1570 °C range, where Ti3SiC2 formation becomes significantly slower. Additions of aluminum are known to reduce the crystallization temperature of the Ti–Si melt, thereby increasing the time during which TiC can react with the liquid and form the MAX phase during cooling. For example, the SHS system 3Ti–Si–2C–0.1Al (at. %) synthesized under argon after vacuum drying yielded a product containing 89 wt. %1 Ti3SiC2 [23]. The authors noted that the addition of aluminum to the stoichiometric 3Ti + Si + 2C mixture suppresses the reaction responsible for TiC formation, which in turn increases the Ti3SiC2 yield. In the SHS system 3Ti + 1.2Si + 2C + 0.1Al, the Ti3SiC2 phase yield reached approximately 83 %, accompanied by 13 % TiC and 4 % Ti5Si3 in the product [24]. The beneficial role of a slight silicon excess has also been repeatedly emphasized [25–27], and may likewise be attributed to the crystallization behavior of the Ti–Si melt [28–30].

According to the Ti–Si phase diagram, at 50 at. % Si the crystallization temperature is 1570 °C; a slight Si excess reduces it to about 1480 °C, and at >67 at. % Si it decreases further to approximately 1330 °С.

Copper additions of 5–10 % to Ti and Si also reduce the melting temperatures of the corresponding binary systems [31; 32] and may therefore lower the crystallization temperature of the Ti–Si–Cu melt, potentially promoting an increased Ti3SiC2 yield. However, Ti3SiC2 is known to decompose in contact with molten Cu via Si deintercalation, forming Cu(Si) and TiCx [33; 34].

Additions of 10 at. % Cr reduce the melting temperatures of Ti–Cr and Si–Cr alloys from 1670 to 1550 °C and from 1414 to 1305 °C, respectively [35; 36].

No data have been reported on the interaction of molten Cr with Ti3SiC2 , which is attributed to the high melting temperature of chromium (1856 °C), while Ti3SiC2 begins to decompose at about 1450 °С [1].

Controlling the mechanism of Ti3SiC2 formation under SHS conditions offers the possibility of developing energy-efficient and technologically simple synthesis routes for MAX phases. Typically, SHS of Ti3SiC2 is carried out in sealed reactors under protective atmospheres or in vacuum, which significantly increases production costs and limits scalability. Therefore, the present study aims to identify a simpler and more accessible method for synthesizing Ti3SiC2 with minimal secondary phases. This work focuses on evaluating the effects of Si, Al, Cu, Cr, and TiSi2 additions on Ti3SiC2 formation during reactor-free SHS in air under a sand bed.

Materials and methods

Powders used as starting reagents for synthesis included porous titanium powder TPP-7 with a coarse particle size (d ~ 300 µm, purity 98 %), technical carbon T900 (d ~ 0.15 µm, agglomerates up to 10 µm, purity 99.8 %), colloidal graphite C-2 (d ~ 15 µm, purity 98.5 %), silicon Kr0 (d ~ 1–15 µm, purity 98.8 %), aluminum PA-4 (d ~ 100 µm, purity 98 %), copper PMS-1 (d ~ 100 µm, purity 99.5 %), chromium Kh99N1 (d ~ 100 µm, purity 99.0 %), and titanium disilicide TiSi2 (d ~ 100 µm, purity 99.0 %).

The starting powders were weighed on a laboratory balance with an accuracy of 0.01 g and mixed in a ceramic mortar for 5 min to obtain homogeneous mixtures corresponding to the following systems: 3Ti–Si–2C + 0.1Al, 3Ti–Si–2C + 0.1Cu, and 3Ti–Si–2C + 0.1Cr, as well as TiSi2–C, where elemental Si and Ti were replaced by TiSi2 in amounts of 15, 50, and 100 % (complete substitution), calculated for the formation of Ti3SiC2 MAX phase.

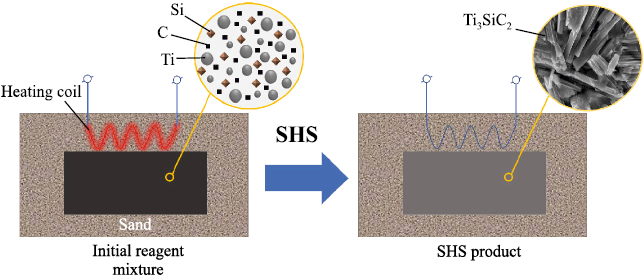

Cylindrical compacts with a diameter of 23 mm and a mass of 20 g were produced from the prepared powder mixtures by single-action pressing at 22.5 MPa. SHS (combustion) was initiated using an electrically heated Ni–Cr coil. The samples were synthesized by combustion in air under a sand layer, which reduces oxidation of the combustion products [25]. The general scheme of the experiment is shown in Fig. 1. As seen, the pressed powder mixture is completely isolated from the ambient air by the sand bed to limit oxidation of the reaction products. After the SHS reaction, secondary Ti3SiC2 formation processes proceed in the cooling sample, also under the sand layer.

Fig. 1. Принципиальная схема синтеза Ti3SiC2 под слоем песка |

Microstructural examination and chemical analysis were performed using a Tescan Vega3 (Czech Republic) scanning electron microscope equipped with an X-act energy-dispersive spectroscopy attachment. The phase composition was determined by X-ray diffraction using an ARL X’trA-138 diffractometer (Switzerland) with CuKα radiation, operated in continuous-scan mode over 2θ = 5–80° at a scan rate of 2°/min. Quantitative phase analysis was carried out using the reference intensity ratio (RIR) method.

Results and discussion

The SHS reaction produces a porous skeleton, which has been repeatedly described in previous studies [9; 12; 25]. After mechanical pulverization, the SHS skeleton is converted into a fine powder, and its particle-size distribution is adjusted using sieves of the required mesh size.

To evaluate the possibility of increasing the Ti3SiC2 MAX-phase yield during SHS in air, a series of experiments was performed in which 10 % of Si, Cr, Al, or Cu was added to the 3Ti–1Si–2C charge composition.

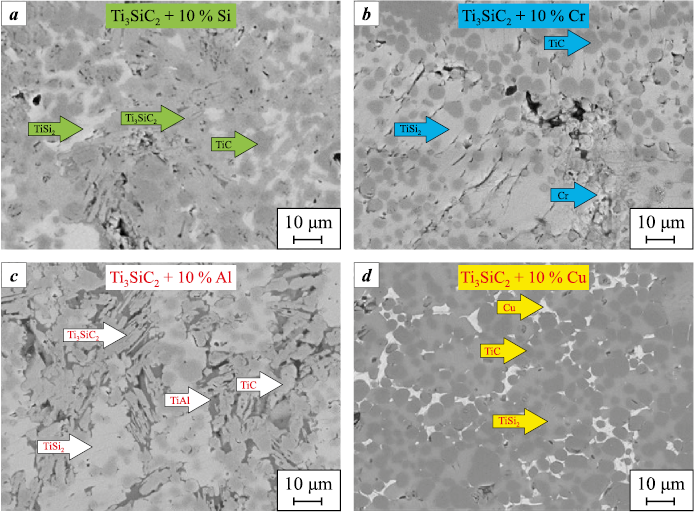

In the sample obtained with an excess of silicon (Fig. 2, a), the unreacted titanium carbide is non-stoichiometric and corresponds approximately to TiC0.6 . Elemental analysis of the lighter Ti–Si regions showed an atomic ratio Si:Ti = 60:40, which is consistent with TiSi2 . The layered morphology and elemental ratios also confirm the presence of Ti3SiC2 regions. A similar microstructural pattern is observed when 10 % Cr is added (Fig. 2, b); however, in this case only trace amounts of Ti3SiC2 are present, while chromium is concentrated within the TiSi2 phase. In the Cu-containing sample (Fig. 2, d), the light-grey regions contain predominantly copper and silicon in a ratio of about 50:15, along with up to 10 at. % carbon. No Ti3SiC2 MAX phase is detected, and the non-stoichiometric titanium carbide corresponds to TiC0.5 . Despite the presence of significant amounts of TiSi2 in direct contact with TiC0.5 , Ti3SiC2 does not form under these conditions. These findings suggest that additions of 10 % Cu or Cr inhibit the formation of Ti3SiC2 ; however, the mechanism governing their influence on MAX-phase formation under SHS conditions requires further study. This may be due to the fact that Cu and Cr cannot occupy the A-site in MAX phases, and their presence in the Ti–Si melt hinders Ti3SiC2 structural formation.

Fig. 2. Microstructures of the samples after introducing 10 % (0.1 mol) |

In the sample containing aluminum (Fig. 2, c), thin dark-grey regions surrounding the Ti3SiC2 platelets were observed. EDS results indicate that these regions correspond to a mixture of TiAl2 and TiSi2 . The crystallization temperature of TiAl2 (1175 °C) is significantly lower than that of the Ti–Si melt (1330–1480 °C, depending on the Ti/Si ratio). Considering that Ti3SiC2 forms via the interaction of solid TiC with liquid Ti–Si, it can be inferred that Al reduces the crystallization temperature of the Ti–Si melt, extending the time during which the melt remains liquid under SHS conditions. This prolongs its interaction with TiC and allows Ti3SiC2 structure formation to continue for a longer duration, ultimately increasing the MAX-phase content in the SHS product.

These observations are consistent with previous findings reported in [25], where the addition of Al increased the Ti3SiC2 yield under reactor-based SHS conditions. The authors showed that a combined excess of 20 % Si and 10 % Al in the Ti:Si:C:Al = 3:1.2:2:0.1 system increases the Ti3SiC2 content from 64 to 83 %.

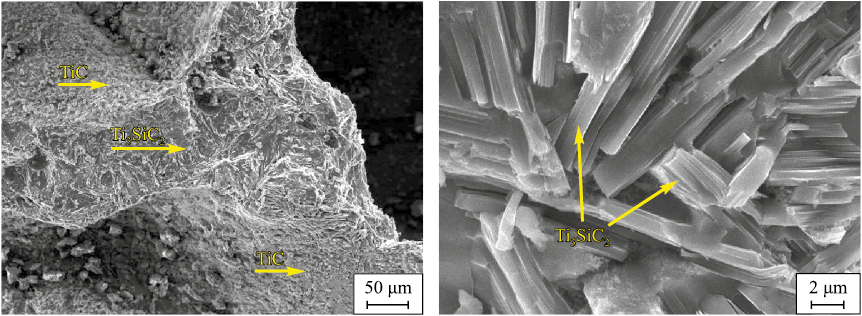

It is reasonable to assume that further optimization of the 3Ti–1xSi–2C–yAl system, with respect to both the silicon excess (x) and the aluminum addition (y), may produce even higher Ti3SiC2 yields during SHS in air. To verify this, several charge compositions containing different silicon excesses and Al additions were investigated. The results are presented in Table 1. A silicon excess of 15–25 % combined with 10 % Al substantially increases the Ti3SiC2 content, reaching a maximum of ~89 vol. % in the 3Ti–1.25Si–2C + 0.1Al system. Varying the Al amount in the absence of excess Si does not significantly affect the Ti3SiC2 yield, which remains within 38–47 vol. %. Microstructural images of the sample containing the maximum Ti3SiC2 content are shown in Fig. 3. The sample consists predominantly of characteristic, randomly oriented Ti3SiC2 platelets, while the pore surfaces are coated with a thin (10–15 µm) layer of densely packed equiaxed TiC particles. The width of most Ti3SiC2 platelets ranges from 2 to 5 µm, and their length varies between 10 and 50 µm.

Phase composition of SHS products in the 3Ti–xSi–2C + yAl system

Fig. 3. SEM images of the microstructure of the sample synthesized |

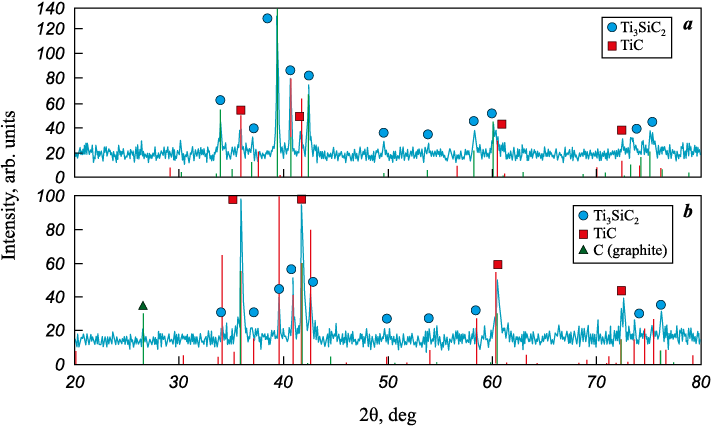

Diffraction patterns of the SHS products with the highest and lowest Ti3SiC2 contents are shown in Fig. 4. Based on these data (Fig. 4, a), the intensity ratio of the main Ti3SiC2 peaks (39.5 and 42.4°) to the TiC peaks (36.0 and 41.8°) corresponds to approximately 80 vol. % Ti3SiC2 . In Fig. 4, b, the TiC peaks are significantly more intense than those of Ti3SiC2 , which is consistent with ~30 % Ti3SiC2 in the product. In addition, distinct graphite peaks (at ~26.5°) are observed in all samples listed in Table 1, as illustrated in Fig. 4, b. This indicates that part of the carbon does not completely react during SHS. Notably, the initially amorphous carbon black used as a reagent becomes crystallized into graphite during combustion, as described previously for Ti–C SHS systems [37; 38]. A slight shift of certain Ti3SiC2 peaks is also observed, which may indicate partial incorporation of Al into the Ti3SiC2 lattice during SHS, a phenomenon previously noted in the literature [23].

Fig. 4. XRD patterns of the 3Ti–1.25Si–2C + 0.1Al (a) and 3Ti–1.00Si–2C + 0.05Al (b) systems |

Porous SHS skeletons were also synthesized using TiSi2 as a chemical reagent to replace elemental Ti and Si in quantities of 10, 50, and 100 %. Analysis of the XRD patterns revealed that such substitution results in an increased amount of secondary phases compared to the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase (Fig. 5). A new secondary phase, SiC, also appears. The maximum Ti3SiC2 content in this series – 56 % – was obtained when silicon was replaced by 10 % TiSi2 . However, increasing the TiSi2 fraction to 100 % reduced the Ti3SiC2 content to 20 %. For comparison, SHS conducted using elemental Ti, Si, and C powders in the stoichiometric 3Ti–1Si–2C charge composition yields up to 66 % Ti3SiC2 [25]. This reduction may be attributed to insufficient temperature in the TiSi2-containing SHS systems, which shortens the lifetime of the Ti–Si melt and prevents the Ti3SiC2 structure-formation process from fully completing.

Fig. 5. Dependence of the phase composition of the SHS product on the degree |

Conclusions

1. It was established that the combined addition of excess Si and Al in the 3Ti–1.25Si–2C + 0.1Al charge composition substantially increases the Ti3SiC2 content, reaching ~89 vol. % under SHS conditions in air using a sand layer without a reactor or protective atmosphere.

2. Additions of Cu and Cr in the 3Ti–1Si–2C + 0.1Cu and 3Ti–1Si–2C + 0.1Cr systems lead to an almost complete suppression of Ti3SiC2 formation in the SHS product.

3. Partial (10 and 50 %) and complete (100 %) substitution of the elemental Ti and Si powders with TiSi2 significantly reduces the yield of the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase during SHS in air.

4. It is likely that further optimization of the 3Ti–1.25Si–2C + 0.1Al system with respect to the particle-size distribution of the starting powder reagents, as well as scale-up factors, may allow the Ti3SiC2 content to exceed 90 % under reactorless SHS conditions.

References

1. Barsoum M.W. MAX phases: Properties of machinable ternary carbides and nitrides. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2013. P.188–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527654581

2. Gonzalez-Julian J. Processing of MAX phases: From synthesis to applications. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2020;104:659–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.17544

3. Wu Q., Li C., Tang H. Surface characterization and growth mechanism of laminated Ti3SiC2 crystals fabricated by hot isostatic pressing. Applied Surface Science. 2010;256(23):6986–6990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.05.012

4. Liu X., Zhang H., Jiang Y., He Y. Characterization and application of porous Ti₃SiC₂ ceramic prepared through reactive synthesis. Materials and Design. 2015;79:94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2015.03.061

5. El-Raghy T., Wiederhorn S., Luecke W., Radovic M., Barsoum M. Effect of temperature, strain rate and grain size on the mechanical response of Ti3SiC2 in tension. Acta Materialia. 2002;50(6):1297–1306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(01)00424-4

6. He X., Bai Y., Li Y., Zhu C., Kong X. In situ synthesis and mechanical properties of bulk Ti₃SiC₂/TiC composites by SHS/PHIP. Materials Science and Engineering A. 2010;527(18-19):4554–4559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2010.04.006

7. Levashov E.A., Mukasyan A.S., Rogachev A.S., Shtansky D.V. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of advanced materials and coatings. International Materials Reviews. 2016;62(4):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09506608.2016.1243291

8. Amosov A.P., Borovinskaya I.P., Merzhanov A.G. Powder technology of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of materials: Textbook. Ed. by V.N. Antsiferov. Moscow: Mashinostroenie-1, 2007. 567 р. (In Russ.).

9. Umerov E.R., Latukhin E.I., Amosov A.P., Kichaev P.E. Preparation of Ti3SiC2–Sn(Pb) cermet by SHS of Ti3SiC2 porous skeleton with subsequent spontaneous infiltration with Sn–Pb melt. International Journal of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. 2023;32(1):30–35. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1061386223010089

10. Feng A., Orling T., Munir Z.A. Field-activated pressure-assisted combustion synthesis of polycrystalline Ti3SiC2. Journal of Materials Research. 1999;14(3):925–939. https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.1999.0124

11. Du Y., Schuster J.C., Seifert H.J., Aldinger F. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic calculation of the titanium–silicon–carbon system. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2000;83(1):197–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01170.x

12. Amosov A.P., Latukhin E.I., Ryabov A.M. SHS process application in Ti3SiC2–Ni composite fabrication. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings. 2018;(4):48–61. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2018-4-48-61

13. Konovalikhin S.V., Kovalev D.Yu., Sytschev A.E., Vadchenko S.G., Shchukin A.S. Formation of nanolaminate structures in the Ti–Si–C system: A crystallochemical study. International Journal of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. 2014;23(4):216–220. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1061386214040049

14. Kachenyuk M.N. Formation of the structure and properties of ceramic materials based on titanium, zirconium, and silicon compounds during consolidation by spark plasma sintering. Diss. of Dr. Sci. (Eng.). Perm; 2022. . 283 p. (In Russ.).

15. Meng F., Liang B., Wang M. Investigation of formation mechanism of Ti3SiC2 by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2013;41:152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2013.03.005

16. Hwang S.S., Lee S.C., Han J., Lee D., Park S. Machinability of Ti3SiC2 with layered structure synthesized by hot pressing mixture of TiCx and Si powder. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2012;32(12):3493–3500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.04.021

17. Yeh C.-L., Lai K.-L. Effects of TiC, Si, and Al on combustion synthesis of Ti3SiC2/TiC/Ti3Si2 composites. Materials. 2023;16(18):6142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16186142

18. Li S.-B., Xie J.-X., Zhang L.-T., Cheng L.-F. In situ synthesis of Ti3SiC2/SiC composite by displacement reaction of Si and TiC. Materials Science and Engineering A. 2004;381(1-2):51–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2004.03.046

19. Zhang Z.F., Sun Z.M., Hashimoto H., Abe T. A new synthesis reaction of Ti3SiC2 through pulse discharge sintering Ti/SiC/TiC powder. Scripta Materialia. 2001; 45(12):1461–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(01)01184-8

20. Yeh C.L., Shen Y.G. Effects of SiC addition on formation of Ti3SiC2 by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2008;461(1-2): 654–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.07.088

21. Yeh C.L., Shen Y.G. Effects of TiC addition on formation of Ti3SiC2 by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2008;458(1-2): 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.04.225

22. Sun Z.M., Murugaiahc A., Zhen T., Zhou A., Barsoum M.W. Microstructure and mechanical properties of porous Ti3SiC2 . Acta Materialia. 2005;53(16):4359–4366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2005.05.034

23. Gubarevich A.V., Tamura R., Maletaskić J., Yoshida K., Yano T. Effect of aluminium addition on yield and microstructure of Ti3SiC2 prepared by combustion synthesis method. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2019;16: 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.05.244

24. Yeh C.L., Lai K.L. Effects of excess Si and Al on synthesis of Ti3SiC2 by self-sustaining combustion in the Ti–Si–C–Al system. Journal of the Australian Ceramic Society. 2024;60(3):959–969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41779-023-00947-y

25. Davydov D.M., Umerov E.R., Amosov A.P., Latukhin E.I. Influence of starting reagents on the formation of Ti3SiC2 porous skeleton by SHS in air. International Journal of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. 2024;33(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1061386224010023

26. Wakelkamp W.J.J., van Loo F.J.J., Metselaar R. Phase relations in the Ti–Si–C system. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 1991;8(3):135–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/0955-2219(91)90067-A

27. Tabares E., Jiménez-Morales A., Tsipas S.A. Study of the synthesis of MAX phase Ti3SiC2 powders by pressureless sintering. Boletin de la Sociedad Espanola de Ceramica y Vidrio. 2021;60(1):41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2020.01.004

28. Lepakova O.K., Itin V.I., Astafurova E.G., Erkaev P.A., Kitler V.D., Afanasyev N.I. Synthesis, phase composition, structure and strength properties of porous materials based on Ti3SiC2 compound. Fizicheskaya mezomekhanika. 2016;19(2):108–113. (In Russ.).

29. Zhou C.L., Ngai T.W.L., Lu L., Li Y.Y. Fabrication and characterization of pure porous Ti3SiC2 with controlled porosity and pore features. Materials Letters. 2014;131:280–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2014.05.198

30. El Saeed M.A., Deorsola F.A., Rashad R.M. Optimization of the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase synthesis. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2012;35:127–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2012.05.001

31. Eremenko V.N., Buyanov Y.I., Prima S.B. Phase diagram of the system titanium–copper. Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics. 1966;5(6):494–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00775543

32. Olesinski R.W., Abbaschian G.J. The Cu–Si (copper–silicon) system. Bulletin of Alloy Phase Diagrams. 1986;7(2):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02881559

33. Zhou Y., Gu W. Chemical reaction and stability of Ti3SiC2 in Cu during high-temperature processing of Cu/Ti3SiC2 composites. International Journal of Materials Research. 2004;95(1):50–56. https://doi.org/10.3139/146.017911

34. Amosov A.P., Latukhin E.I., Ryabov A.M., Umerov E.R., Novikov V.A. Application of SHS process for fabrication of copper–titanium silicon carbide composite (Cu–Ti3SiC2). Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2018;1115(4):042003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1115/4/042003

35. Murray J.L. The Cr–Ti (chromium–titanium) system. Bulletin of Alloy Phase Diagrams. 1981;2(2):174–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02881474

36. Gokhale A.B., Abbaschian G.J. The Cr–Si (chromium–silicon) system. Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion. 1987;8(5):474–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02893156

37. Shcherbakov V.A., Gryadunov A.N., Karpov A.V., Sachkova N.V., Sychev A.E. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of TiC + xC composites. Inorganic Materials. 2020;56(6):567–571. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020168520060102

38. Umerov E.R., Amosov A.P., Latukhin E.I., Novikov V.A. SHS of TiC–graphite porous composites and carbon graphitization. International Journal of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. 2025;34(1):42–49. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1061386224700407

About the Authors

E. R. UmerovRussian Federation

Emil R. Umerov – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Leading Researcher of the Department of metal science, powder metallurgy, nanomaterials (MPMN)

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

S. A. Kadyamov

Russian Federation

Shamil A. Kadyamov – Postgraduate Student of the Department of MPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

D. M. Davydov

Russian Federation

Denis M. Davydov – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Junior Researcher of the Department of MPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

E. I. Latukhin

Russian Federation

Evgeny I. Latukhin – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor of the Department of MPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

A. P. Amosov

Russian Federation

Aleksandr P. Amosov – Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Prof., Head of the Department of MPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

Review

For citations:

Umerov E.R., Kadyamov S.A., Davydov D.M., Latukhin E.I., Amosov A.P. Effect of Si, Al, Cu, Cr, and TiSi2 on the formation of the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase during self-propagating high-temperature synthesis in air. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):27-35. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-27-35