Scroll to:

Aluminum matrix composites Al–SiO2 produced using amorphous microsilica

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-44-51

Abstract

Studies were carried out to develop aluminum matrix composites reinforced with amorphous microsilica particles. The feasibility of producing Al–5 wt. % SiO2 materials using both stirring-assisted casting and semisolid metal processing was established. The latter method, when combined with subsequent squeeze casting, demonstrated the highest efficiency. Magnesium was shown to function as a surface-active additive that removes oxygen from the surfaces of the dispersed particles and enhances the mechanical properties of the composite during heat treatment. The resulting material exhibits a uniform distribution of microsilica particles throughout the aluminum matrix and demonstrates hardness, corrosion resistance, and reduced specific weight superior to those of the base AlSi7 alloy. Therefore, the composites produced using the developed technology are promising for applications in transport engineering as well as in the aerospace and space industries.

Keywords

For citations:

Kuz’min M.P., Kuz’mina M.Yu., Kuz’mina A.S. Aluminum matrix composites Al–SiO2 produced using amorphous microsilica. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):44-51. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-44-51

Introduction

The advancement of modern engineering is inseparable from the use of materials – both alloys and composites – possessing specific physical, chemical, mechanical, and operational properties, as well as from the continuous improvement of technologies for their production.

The development of composite materials consisting of a metallic matrix reinforced by dispersed particles is among the highest-priority directions in contemporary metallurgy and materials science. In many cases, only composites can meet the stringent requirements of advanced engineering applications, which increasingly demand higher loads, operational speeds, temperatures, environmental aggressiveness, and reduced structural weight. Among metal-matrix composites, aluminum-based systems are the most widely used owing to their high specific strength, low density, and advantageous combinations of mechanical and operational properties [1–10].

A broad range of technologies is available for the fabrication of aluminum matrix composites (AMCs), including powder metallurgy, mechanical dispersion, liquid metal infiltration, and various casting techniques [1; 4; 11]. Casting assisted by intensive stirring is the most accessible and widely employed method. This process involves introducing reinforcing particles into molten aluminum followed by mechanical or electromagnetic stirring [12–14]. A known limitation of this method is the agglomeration of the added particles due to their inherently low wettability in an aluminum melt [15].

Several studies have demonstrated that semisolid metal processing (SSM) represents one of the most cost-effective approaches to producing aluminum matrix composites. In this method, the melt is processed within the temperature interval between liquidus and solidus, where the alloy exhibits a slurry-like rheology, enhancing particle incorporation [16; 17]. Three closely related SSM routes are distinguished: thixocasting, rheocasting, and thixomolding [18–20]. To reduce porosity and refine the microstructure of finished products, high-pressure die casting is commonly applied as an auxiliary step [21]. Most research on AMCs focuses on reinforcing particles such as Al2O3 , ZrO2 , MgO, SiC, as well as carbon nanotubes [10–30]. The use of dispersed reinforcing materials is limited by the technological complexity of composite fabrication and by their cost, which is strongly influenced by market conditions and varies significantly among different types of ceramic powders depending on their chemical composition, particle size, and degree of purity.

In recent years, significant effort has been directed to ward reducing the cost of AMC production by employing inexpensive and widely available raw materials. In this study, microsilica – an ultrafine material composed of spherical SiO2 particles – is used as a modifying agent [4; 5]. Depending on the manufacturer, its market price ranges from 550 to 870 USD/t. A promising route to cost reduction is the use of dust collected from gas-cleaning systems of silicon-production furnaces as a low-cost source of microsilica (~1500 RUB/t) [11].

The aim of the present study was to develop a method for producing Al–SiO2 composites containing up to 5 wt. % of reinforcing particles using intensive stirring casting and semisolid metal processing, and to evaluate the influence of SiO2 particles on their microstructure and properties.

Materials and methods

For the laboratory studies aimed at producing composites using amorphous silica, a hypoeutectic AlSi7 silumin alloy was used as the matrix metal; its chemical composition was as follows (wt. %):

Si . . . . . . . . . 7.00

Fe . . . . . . . . 0.19

Mg . . . . . . . 0.25

Mn . . . . . . . 0.10

Cu . . . . . . . . 0.05

Zn . . . . . . . . 0.07

Ga . . . . . . . . 0.001

Amorphous microsilica was collected from the gas-cleaning system of JSC Kremniy (Shelekhov, Russia) and enriched by flotation [17]. To improve the wettability of the microsilica particles and suppress agglomeration during their introduction into the melt, the powder was subjected to ultrasonic treatment in acetone, rinsing with distilled water, drying, and subsequent heat treatment at 200–300 °C. In parallel with thermal conditioning of the microsilica, the melt was alloyed with magnesium, added as MG-90 master alloy in an amount of 1 wt. % to enhance interfacial wetting.

Two processing routes were employed to produce the aluminum matrix composites:

– intensive mechanical stirring followed by gravity casting;

– semisolid metal processing followed by squeeze casting.

To enable an objective comparison of the microstructure and physicomechanical properties, the base aluminum alloy was remelted using the continuous casting method.

During stirred casting, microsilica particles were introduced at 730 °C, whereas in semisolid processing they were introduced at 585–615 °C, i.e., between the solidus and liquidus temperatures of the AlSi7 alloy. All subsequent casting operations were performed at temperatures above the liquidus (730 °C). The SiO2 particles, preheated to 200–300 °C, were fed into the melt at 5 g/min while the melt was stirred with a rotor at 200 rpm. The final forming step consisted of squeeze casting on a 25-ton hydraulic press. After that, the ingots were subjected to heat treatment at 500 °C for 14 h, followed by quenching in warm water (70 °C) and precipitation, or age hardening, at 165 °C for 8 h. The T6 heat-treatment mode was applied to both the unreinforced alloy and the composite and consisted of solution treatment at 525 °C for 12 h, followed by quenching in warm water at 80 °C and aging at 165 °C for 8 h.

Phase analysis was performed using a Shimadzu XRD-7000 diffractometer within a 2θ range of 10–70°. Microstructural analysis in secondary-electron and backscattered-electron modes was carried out using a JEOL JIB-4500 scanning electron microscope equipped with an Oxford Instruments X-Max EDS detector. Metallographic observations were conducted using an Olympus GX-51 optical microscope. Hardness was measured using a Zwick Brinell hardness tester with a 2.5-mm indenter and a 62.5-kg load. Corrosion behavior was examined by potentiodynamic polarization using a three-electrode cell with a saturated calomel reference electrode and platinum counter electrode. Density was measured by hydrostatic weighing according to GOST 8.568-97. Cubic samples (10 mm edge length) were degreased and dried at 105 °C for 1 h to remove adsorbed moisture.

Results and discussion

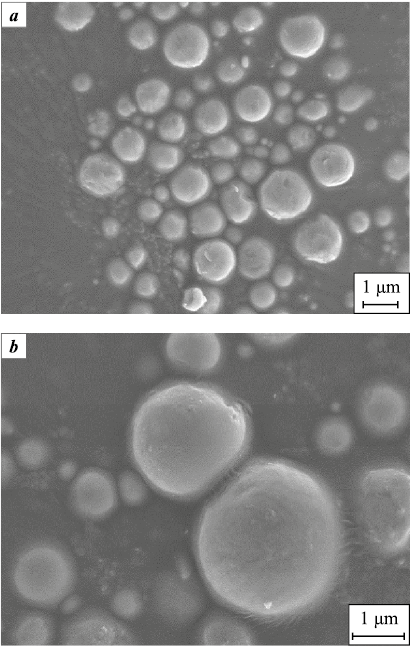

SEM images of the spherical microsilica particles (Fig. 1) reveal a wide particle-size distribution and the adhesion of smaller particles to the surfaces of larger spheres due to their high surface energy (Fig. 1, b).

Fig. 1. SEM images of microsilica particles |

The microsilica used in this study had the following chemical composition (wt. %):

SiO2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95.0

Al2O3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.55

Fe2O3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.61

CaO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.96

MgO . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.21

Na2O . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.31

K2O . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.84

C . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.25

S . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.27

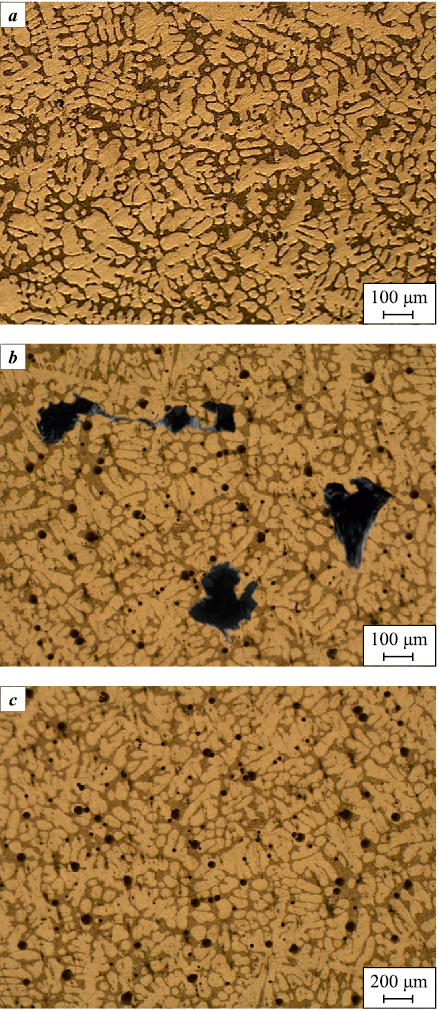

Fig. 2, a shows the microstructure of the initial hypoeutectic AlSi7 silumin, consisting of dendrites of the aluminum solid solution (α-Al) and the α-Al + Si eutectic located in the interdendritic regions.

Fig. 2. Microstructures of the base AlSi7 alloy (a), the composite produced |

The AlSi7 alloy produced by high-pressure die casting exhibits a refined microstructure with an average grain size of 15 μm and no shrinkage or gas porosity. The microstructure of the Al–SiO2 composite produced by casting with intensive mechanical stirring and subsequent pouring at 720 °C (Fig. 2, b) is characterized by agglomeration of the microsilica particles and the formation of regions of shrinkage porosity. This indicates a high degree of SiO2 particle agglomeration, which increases in direct proportion to the casting temperature.

Fig. 2, c presents the microstructure of the Al–SiO2 composite fabricated via semisolid metal processing at 600 °C with intensive mechanical stirring followed by squeeze casting. Under these conditions, the composite exhibits a uniform distribution of the microsilica particles throughout the material, to gether with grain refinement and the elimination of shrinkage porosity. Because the squeeze-casting process allows the metal to be processed in the form of a semisolid slurry, the dispersed reinforcing particles become highly uniformly distributed and their agglomeration is effectively prevented.

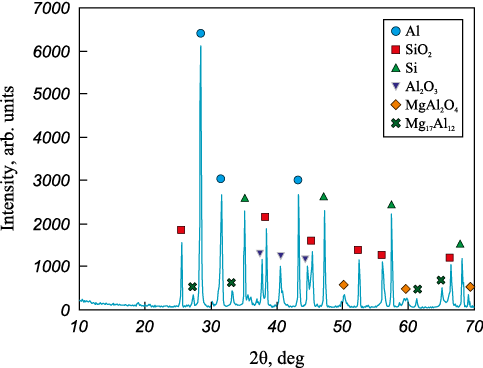

Semisolid processing was conducted within the temperature interval between the liquidus and solidus, during which the alloy containing primary α-Al dendrites was stirred at 590 °C. Processing the alloy in this semisolid state enabled a uniform distribution of the SiO2 particles throughout the matrix – an outcome that could not be achieved by intensive stirring of the fully molten metal. The diffraction pattern of this sample shows reflections corresponding to Al, Si, and SiO2 (Fig. 3). The most intense peaks arise from metallic aluminum (2θ = 28.7°, 32.4°, 43.5°), crystalline silicon (2θ = 35.1°, 47.4°, 57.5°, 68.4°), silicon dioxide (2θ = 25.5°, 38.1°, 45.3°, 52.7°, 57.3°, 66.5°), and aluminum oxide (2θ = 37.6°, 41.9°, 44.8°). X-ray diffraction also revealed the presence of MgAl2O4 and Mg17Al12 , formed as a result of the additional magnesium introduced into the base silumin alloy. Magnesium improves the wettability of the microsilica particles by the aluminum matrix through the formation of MgAl2O4 spinel, which removes surface oxides [10; 17]. The Mg17Al12 phase formed during heat treatment further contributes to strengthening of the composite.

Fig. 3. Diffraction pattern of the Al–SiO2 composite in the 2θ range of 10÷70° |

The results show that the SiO2 content in the composite material matches the target value of 5 wt. %. This demonstrates that the amount of dispersed particles introduced into the aluminum matrix can be accurately controlled. However, to avoid the formation of the Al3Mg2 intermetallic phase, which degrades the strength of the composite, the magnesium addition to the aluminum matrix should be limited to 2 wt. %.

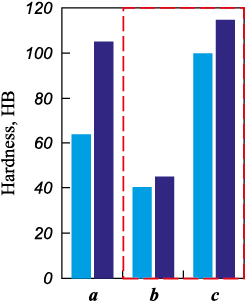

Brinell hardness data for the cast AlSi7 silumin and the composites produced from it by the different processing routes are presented in Fig. 4. These results indicate that the incorporation of amorphous microsilica particles into the cast silumin, provided they are uniformly distributed, leads to an increase in hardness. The SiO2 particles in the aluminum matrix act as nucleation centers and promote grain refinement, while the mismatch in the coefficients of thermal expansion between the microsilica and the matrix alloy generates interfacial strain, which serves as a barrier to dislocation motion.

Fig. 4. Brinell hardness of the base AlSi7 alloy (a) and of the composites |

The hardness of the composite materials is governed primarily by the processing route and by the degree of dispersion of the reinforcing particles. The composite obtained by casting with intensive mechanical stirring shows, even after heat treatment, a marked reduction in hardness relative to the base AlSi7 alloy. This deterioration is associated with the pronounced agglomeration of microsilica particles and the resulting formation of shrinkage porosity. By contrast, the composite produced by semisolid metal processing followed by squeeze casting exhibits the highest hardness. This improvement is due to the more uniform dispersion of microsilica throughout the matrix and to grain refinement caused by crystallization under pressure in the presence of numerous nucleation sites.

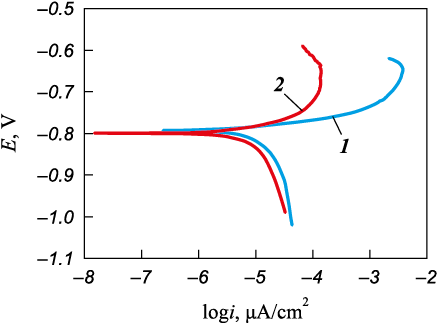

The tensile strength of the composite produced by semisolid metal processing was 257 MPa, which is essentially equal to that of the base AlSi7 alloy (σb = 269 MPa). In addition to its high strength, this composite showed enhanced corrosion resistance (Fig. 5). This enhancement is attributed to the formation of interfacial reaction products arising from the interaction of aluminum, magnesium, and microsilica, which are less susceptible to corrosive attack. Phases such as MgAl2O4 , Al2O3 , and SiO2 form a protective oxide layer on the material surface.

Fig. 5. Potentiodynamic polarization curves of the base AlSi7 alloy (1) |

The density of the composite obtained by casting with intensive mechanical stirring is slightly lower (2.58 g/cm3) than that of the base alloy (2.64 g/cm3). This reduction is explained by the presence of shrinkage porosity and agglomerates of SiO2 particles, as revealed by microstructural analysis (Fig. 2, b).

The lowest density (2.47 g/cm3) was measured for the composite produced by semisolid casting followed by squeeze casting. Despite its lower density, this material exhibited the best mechanical properties and no macroporosity. The main reasons for the reduced density in this case are.

1. The presence of a low-density reinforcing phase. Amorphous SiO2 particles have a density of about 2.2 g/cm3, which is lower than that of the aluminum matrix (~2.7 g/cm3). The addition of 5 wt. % SiO2 therefore naturally reduces the overall density of the composite.

2. Densification under pressure. Squeeze casting produces a material with a more homogeneous microstructure and minimal porosity, as confirmed by the micrographs (Fig. 2, c).

Thus, in this case the decrease in density is not associated with defects but rather with the uniform distribution of the lightweight ceramic phase within the metallic matrix.

Conclusions

This study confirms the feasibility of producing Al–SiO2 composites using intensive stirring casting and semisolid metal processing with subsequent squeeze casting. The latter method proved most effective, enabling the fabrication of composites containing 5 wt. % uniformly distributed microsilica particles. The results showed that magnesium enhances the wettability of the dispersed microsilica particles by removing oxygen from their surfaces and by suppressing further oxide formation through the generation of the MgAl2O4 intermetallic phase. An improvement in the mechanical properties of the composite during heat treatment was also observed, which is attributed to the formation of the Mg17Al12 phase. The resulting composite exhibited higher hardness and superior corrosion resistance compared to the base AlSi7 alloy.

The proposed processing routes – casting with intensive mechanical stirring and semisolid metal processing – enable the production of Al–SiO2 composites with high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and low porosity, making them promising for transport engineering as well as the aviation and aerospace industries. The findings expand current understanding of the use of micro- and nanoscale powders as alloying and modifying agents in next-generation composite materials.

References

1. Pattnayak A., Madhu N., Sagar Panda A., Kumar Sahoo M., Mohanta K. A Comparative study on mechanical properties of Al–SiO2 composites fabricated using rice husk silica in crystalline and amorphous form as reinforcement. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2018;5(2): 8184–8192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.507

2. Malek A., Abderraouf Gh. Synthesis and characterization of Al–SiO2 composites. Journal of Ceramic Processing Research. 2019;20(3):259–263. https://doi.org/10.36410/jcpr.2019.20.3.259

3. Nalivaiko A. Yu., Arnautov A.N., Zmanovsky S.V., Ozherelkov D.Yu., Shurkin P.K., Gromov A.A. Al–Al2O3 powder composites obtained by hydrothermal oxidation method: Powders and sintered samples characterization. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2020;825:154024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154024

4. Kuz’min M.P., Ivanov N.A., Kondrat’ev V.V., Kuz’mina M.Yu., Begunov A.I., Kuz’mina A.S., Ivanchik N.N. Preparation of aluminum–carbon nanotubes composite material by hot pressing. Metallurgist. 2018;61(3):815–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-018-0569-2

5. Kuz’min M.P., Kondrat’ev V.V., Larionov L.M., Kuz’mina M.Y., Ivanchik N.N. Possibility of preparing alloys of the Al–Si system using amorphous microsilica. Metallurgist. 2017;60(5):86–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-017-0458-0

6. Sathish T., Chandramohan D. Teaching methods and methodologies used in laboratories. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering. 2019;7(6):291–293.

7. Lepezin G.G., Kargopolov S.A., Zhirakovskii V.Yu. Sillimanite group minerals: A new promising raw material for the Russian aluminum industry. Russian Geology and Geophysics. 2010:51(12):1247–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgg.2010.11.004

8. Bakker H. Enthalpies in alloys. Miedema’s semi-empirical model. Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications. Ltd., 1998. 195 p.

9. Saravanan K.S., Pradhan Raghuram A., Ramya S., Senthilnathan K. Characterization of Al–SiO2 composite material. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology. 2019;9(2):2972–2975. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijeat.B3898.129219

10. Pai B.C., Ramani G., Pillai R.M., Satyanarayana K.G. Role of magnesium in cast aluminium alloy matrix composites. Journal of Materials Science. 1995;30(8):1903–1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00353012

11. Kuz’min M.P., Larionov L.M., Chu P.K., Qasim A.M., Kuz’mina M.Yu., Kondratiev V.V., Kuz’mina A.S., Jia Q. Ran new methods of obtaining Al–Si alloys using amorphous microsilica. International Journal of Metalcasting. 2020;14(1):207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40962-019-00353-w

12. Gowri Shankar M.C., Jayashree P.K., Kini A.U., Sharma S.S. Effect of silicon oxide (SiO2 ) reinforced particles on ageing behavior of Al–2024 Alloy. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology. 2014: 5(9):15–21.

13. Kok M. Production and mechanical properties of Al2O3 particle-reinforced 2024 aluminum alloy composites. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2005;161(3):381–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2004.07.068

14. Taha M.A., El-Mahallawy N.A. Metal–matrix composites fabricated by pressure assisted infiltration of loose ceramic powder. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 1998;73(1-3):139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(97)00223-9

15. Sajjadi S.A., Ezatpour H.R., Parizi M.T. Comparison of microstructure and mechanical properties of A356 aluminum аllоу /Al2O3 composites fabricated by stir and compo–casting processes. Materials and Design. 2012;34: 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2011.07.037

16. Abbasipour B., Niroumand B., Monir vaghefi S.M. Compocasting of A356–CNT composite. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 2010;20(9):1561–1566. https://doi.org/1010.1016/S1003-6326(09)60339-3

17. Kuz’min M.P., Paul K. Chu, Abdul M. Qasim, Larionov L.M., Kuz’mina M.Yu., Kuz’min P.B. Obtaining of Al–Si foundry alloys using amorphous microsilica – Crystalline silicon production waste. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2019;806(4-6):806–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.07.312

18. Robie A.R., Hemingway B.S. Thermodynamic properties of minerals and related substances at 298,15 K and 1 bar (105 pascals) pressure and at higher temperatures. Washington: United States Government Printing Office; 1995. 461 p.

19. Sajjadi S.A., Torabi Parizi M., Ezatpoura H.R., Sedghic A. Fabrication of A356 composite reinforced with micro and nano Al2O3 particles by a developed compocasting method and study of its properties. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2012;511(1):226–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.08.105

20. Cocen L., Onel K. The production of Al–Si alloy–SiCp composites via compocasting: some microstructural aspects. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 1996; 221(1-2):187–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0921-5093(96)10436-6

21. Escalera-Lozano R., Gutierrez С.A., Pech-Canul M.A. Pech-Canul M.I. Corrosion characteristics of hybrid Al/SiCp/MgA12O4 composites fabricated with fly ash and recycled aluminum. Materials Characterization. 2007;58(10):953–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2006.09.012

22. Munasir M., Triwikantoro T., Zainuri M., Bäßler R., Darminto D. Mechanical strength and corrosion rate of aluminium composites (Al/SiO2 ): Nanoparticle silica (NPS) as reinforcement. Journal of Physical Science. 2019;30(1):81–97. https://doi.org/10.21315/jps2019.30.1.7

23. Kuz’min M.P., Larionov L.M., Kondratiev V.V., Kuz’mina M.Yu., Grigoriev V.G., Knizhnik A.V., Kuz’mina A.S. Fabrication of silumins using silicon production waste. Russian Journal of Non–Ferrous Metals. 2019;60(5): 483–491. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821219050122

24. Li G., Hao S., Gao W., Lu Z. The Effect of applied load and rotation speed on wear characteristics of Al–Cu–Li alloy. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance. 2022:31 (1): 5875–5885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-022-06613-x

25. Zheng Zh.-k., Ji Y.-j., Mao W.-m., Yue R., Liu Zh.-y. Influence of rheo-diecasting processing parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of hypereutectic Al−30 % Si alloy. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 2017;27(6):1264–1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(17)60147-X

26. Jeon J.H., Shin J.H., Bae D.H. Si phase modification on the elevated temperature mechanical properties of Al–Si hypereutectic alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2019;748(6):367–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2019.01.119

27. Apakashev R., Davydov S., Valiev N. High-temperature synthesis of composite material from Al–SiO2 . System Components. 2014;1064:58–61. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1064.58

28. Feng H.K., Yu S.R., Li Y.L., Gong L.Y. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on microstructures of hypereutectic Al–Si alloy. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2008;208(1-3):330–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMATPROTEC.2007.12.121

29. Jiang B., Ji Z., Hu M., Xu H., Xu S. A novel modifier on eutectic Si and mechanical properties of Al–Si alloy. Materials Letters. 2019:239:13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2018.12.045

30. Lin Ch., Wu Sh.-s., Lü Sh.-l., Zeng J.-b., An P. Dry sliding wear behavior of rheocast hypereutectic Al–Si alloys with different Fe contents. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 2016;26(3):665–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(16)64156-0

About the Authors

M. P. Kuz’minRussian Federation

Mikhail P. Kuz’min – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor, Department of Metallurgy of Non-Ferrous Metals

83 Lermontov Str., Irkutsk 664074, Russia

M. Yu. Kuz’mina

Russian Federation

Marina Yu. Kuz’mina – Cand. Sci. (Chem.), Associate Professor, Department of Metallurgy of Non-Ferrous

83 Lermontov Str., Irkutsk 664074, Russia Metals

A. S. Kuz’mina

Russian Federation

Alina S. Kuz’mina – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Associate Professor, Department of Radioelectronics and Telecommunication Systems

83 Lermontov Str., Irkutsk 664074, Russia

Review

For citations:

Kuz’min M.P., Kuz’mina M.Yu., Kuz’mina A.S. Aluminum matrix composites Al–SiO2 produced using amorphous microsilica. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):44-51. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-44-51