Scroll to:

Effect of Cu additions and SHS charge compaction pressure on thermite-copper infiltration and the macrostructure of synthesized TiC–Cu cermets

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-52-0

Abstract

TiC–Cu ceramic–metal composites (cermets) have been extensively discussed in recent literature in terms of their properties and structure. However, in most cases the formation conditions considered involve the introduction of TiC particles into an overheated Cu melt. In the present work, samples were synthesized in air without crucible reactors by combining a thermite reaction to produce a copper melt for subsequent infiltration of a porous Ti + C powder charge and initiation of its combustion by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) of titanium carbide. As a result, TiC–Cu cermets were formed. The effect of Cu addition to the Ti + C SHS charge and of compaction pressure on the completeness of infiltration by the copper melt generated during combustion of the copper thermite mixture is analyzed. The influence of these factors on the structure of the synthesized cermets is also examined. TiC–Cu cermets were synthesized with 5, 10, and 15 wt. % Cu added to SHS charges compacted at 22, 34, 45, 56, and 69 MPa. The completeness of infiltration was evaluated from the appearance of polished sections, microstructure, and phase composition. Optimal conditions were identified that provide composites with maximum density, minimal structural defects, the desired phase composition, and enhanced mechanical properties. The microstructure, composition, and physico-mechanical properties (density, Brinell hardness, compressive strength) of the new composites were investigated. It was established that the highest infiltration completeness and density of TiC–Cu samples are achieved at 10 wt. % Cu addition to the SHS charge and a compaction pressure of 45 MPa, while increasing Cu content in the charge leads to higher mechanical properties (hardness and compressive strength).

Keywords

For citations:

Karakich E.A., Umerov E.R., Novikov V.A., Kichaev P.E., Amosov A.P. Effect of Cu additions and SHS charge compaction pressure on thermite-copper infiltration and the macrostructure of synthesized TiC–Cu cermets. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):52-64. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-52-0

Introduction

Copper and copper-based alloys are widely used as structural materials in mechanical engineering due to their high electrical and thermal conductivity and chemical stability. However, these materials exhibit relatively low strength and wear resistance. Improving their mechanical and tribological properties remains an important task aimed at expanding the application range of copper and its alloys, increasing efficiency of use, and enhancing service life and operational reliability. Metal-matrix composites are actively being developed, in which a copper matrix is typically reinforced with hard and stiff particles of ceramics, intermetallics, carbon nanotubes, and similar phases [1–3]. To impart self-lubricating properties, the most common hardening phases include SiC [4], TiC [5], AlN [6], Al2O3 [7], TiB2 [8], WC [9], as well as graphite [10], carbon nanotubes [11], and MoS2 [12]. Titanium carbide is an attractive reinforcement for metallic matrices because it possesses a high elastic modulus, high hardness, a high melting point, and moderate electrical conductivity [13]. In addition, TiC exhibits virtually no interaction with copper; therefore, its incorporation into a copper matrix does not adversely affect the physical or electrical properties of TiC–Cu composites [14].

For producing TiC–Cu composites, powder metallurgy offers several established routes, including conventional sintering, microwave sintering, spark plasma sintering (SPS), and hot pressing. Minimizing residual porosity in such composites requires applying high pressure and temperature to achieve sufficient densification of the initial powder materials. The physical and mechanical properties of TiC–Cu composites are also governed by the adhesion at the metal–ceramic inter-face, which is controlled by the wetting of TiC particles by molten copper. The wetting angle in the TiC–Cu system depends on both temperature and contact time: for example, at 1200 °C it decreases from 130 to 90° within 25 min [15]. Lower temperatures increase the wetting angle. Furthermore, oxidation of TiC surfaces decreases their wettability by molten copper because it inhibits the partial dissolution reactions of titanium carbide in copper that facilitate wetting [16].

The high temperatures and pressures required to fabricate TiC–Cu composites significantly complicate manufacturing and increase energy consumption, which affects their cost. In this regard, the method of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) represents a promising basis for future energy-efficient fabrication technologies for TiC–Cu composites. SHS enables the synthesis of various ceramic compounds through a highly exothermic reaction that does not require external heating, proceeds in a self-sustaining regime, and can raise product temperatures to 2500–3000 °C [17]. For example, STIM-type alloys (synthetic hard tool materials) are produced by adding up to 40–50 vol. % of a metallic binder (copper, nickel, etc.) to an initial Ti + C powder mixture. After initiating the SHS reaction Ti + C → TiC, the binder metal melts, and pressure up to 180 MPa is applied. The resulting TiC–Cu composites can achieve a relative density of 99 % [18]. Further development of this method has led to the fabrication of TiC–TixCuy–Cu composites containing 48–68 %1 TiC, 32–48 % TixCuy intermetallics, and up to 2.5 % free copper, exhibiting high abrasive resistance at hardness levels of 50–52 HRC [19].

A recently developed approach eliminates the need for external pressing equipment: SHS is used to produce porous TiC (or TiC mixed with the MAX-phase Ti3SiC2–TiC), followed by spontaneous infiltration with molten metal (Al, Sn, Cu) without applying external pressure [20–22]. However, when using cop-per melt generated solely by the heat of the SHS TiC reaction from the initial Cu powder, it was found that the available amount of molten copper was insufficient to fill the entire pore volume of the TiC preform. At the same time, preparing copper melt in a furnace at 1100 °C – i.e., using an external heat source – does not provide adequate wetting of TiC at this temperature, preventing spontaneous infiltration of molten copper into the TiC framework. The present work addresses this issue by employing a higher-temperature copper melt generated via the aluminothermic reaction 3CuO + 2Al → Al2O3 + 3Cu, which can heat the copper above its boiling point [23].

SHS can also proceed concurrently with a metallothermic reaction within a single highly exothermic reactive system used to synthesize ceramic–metal composite materials [24; 25]. In [26], TiC–Fe powders were produced via coupled reactions in Fe2O3 + 2Al and Ti + C mixtures in an energy-saving and technologically simple mode. However, the product of the combined SHS and aluminothermic reaction was a highly porous Fe(Al)–Fe3Al–Al2O3–TiC or TiC–Fe cermet that could be easily crushed into powder. To explore the possibility of producing a dense (or low-porosity) cermet, it is promising to separate the aluminothermic and SHS reactions into two independent reactive systems that generate a metal melt and a porous ceramic body (preform) separately. These can then be combined into a monolithic cermet through capillary wetting at the elevated temperature achieved during the aluminothermic and SHS processes.

Earlier [27], we developed a special graphite refractory reactor consisting of two cylindrical crucible-reactors positioned vertically. The working volume of the upper reactor serves for the aluminothermic reaction that produces the copper melt. The lower crucible holds the SHS Ti + C charge that forms the porous TiC ceramic preform. The two reaction chambers are separated by a graphite plate with an opening through which the thermite melt can flow into the lower crucible. To ensure phase separation between the molten copper and alumina produced during aluminothermy, the opening is covered by a copper or steel washer that delays the outflow of the thermite melt for several seconds.

In [28], it was demonstrated that SHS and aluminothermy can be combined without a special two-crucible setup by conducting the synthesis on an open sand substrate, where a compacted SHS briquette is simply surrounded by a copper-thermite mixture. TiC–Cu cermets were obtained in this manner, and it was shown that the compaction pressure of the SHS charge and the addition of 5 % copper significantly influence the phase composition of the materials, which – besides the main phases – may contain TixCuy intermetallics and free graphite. Proper optimization of the SHS charge composition and compaction pressure can ensure uniform TiC–Cu composites with minimized residual porosity and, consequently, enhanced physical and mechanical properties.

The objective of this study was to examine the effect of SHS charge compaction and Cu additions in the SHS mixture on the structure and mechanical properties of TiC–Cu composites produced by combining aluminothermy and SHS in air without refractory crucible reactors.

Materials and methods

Titanium carbide porous preforms were synthesized using titanium powder grade TPP-7 (d ≤ 300 μm, purity 99 %) and carbon in the form of P701 carbon black (d = 13–70 nm, purity 99 %) to prepare a 15 g SHS Ti + C charge. Copper powder PMS-A (d = 100 μm, 99.5 %) was added in amounts of 0, 0.75, 1.5, and 2.25 g to reduce the combustion rate and obtain a more homogeneous TiC preform. A copper thermite mixture (TU 1793-002-12719185-2009), 40 g in total, served both as the SHS ignition source and as the primary source of molten copper. The mixed SHS charge with copper addition was uniaxially compacted using a manual press in a steel die of 23 mm diameter. The minimum compaction pressure was 22 MPa, which provided sufficient strength for handling and preserving the shape of the compact during combustion.

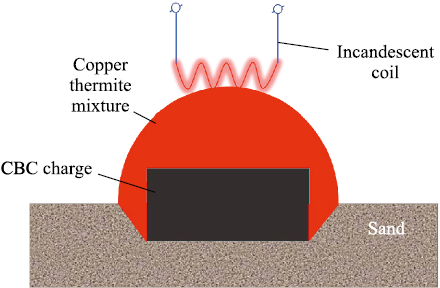

The samples were synthesized by combining aluminothermy and SHS in air without using refractory crucible reactors. Under these conditions, both the aluminothermic reaction 3CuO + 2Al → Al2O3 + 3Cu, with phase separation of the oxide and copper melts followed by release of the latter after melting a thin steel washer [27; 28], and the SHS process producing the porous TiC preform, occurred simultaneously. The overall experimental layout is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the combined aluminothermic reaction |

The compacted cylindrical SHS briquette was placed into a cavity formed in a sand substrate and uniformly covered with the copper thermite mixture. An electrical heating coil initiated the thermite reaction, whose thermal impulse triggered the SHS reaction. During combustion of the copper thermite mixture and formation of the copper melt, a sufficiently high temperature was reached to initiate SHS of the porous TiC preform, which was instantaneously infiltrated by the incoming molten copper through capillary action. As a result of synthesis and spontaneous infiltration, dense TiC–Cu cermet bodies were obtained.

The completeness of preform infiltration was preliminarily assessed by visual examination of polished sample surfaces (macrosections) and by density measurements using the Archimedes method. Microstructural analysis of the synthesized samples was performed using a JSM-7001F scanning electron microscope (Jeol, Japan). The phase composition of the synthesis products was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). Diffraction patterns were recorded on an automated ARL X’trA diffractometer (Thermo Scientific, Switzerland) using CuKα radiation in continuous scan mode over 2θ = 20–80° at 2°/min. The diffraction data were processed using the WinXRD software package. Hardness was measured according to the Brinell method using a 5 mm ball indenter at a load of 98 N in accordance with GOST 9012-59. Compression tests were carried out following GOST 25.503-97 on cylindrical samples with a diameter of 20.1 ± 0.1 mm and a height of 19.4 ± 0.8 mm using a Bluehill 3 testing machine (Instron, USA) at a cross-head speed of 1 mm/min.

Results and discussion

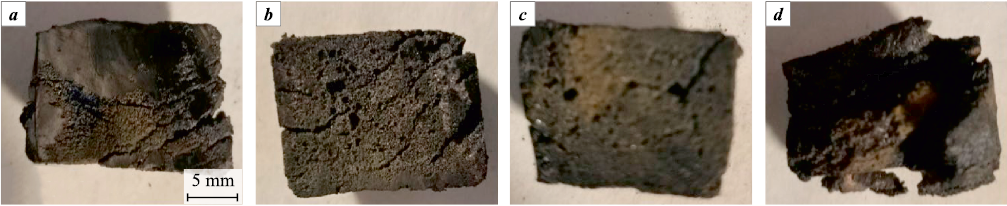

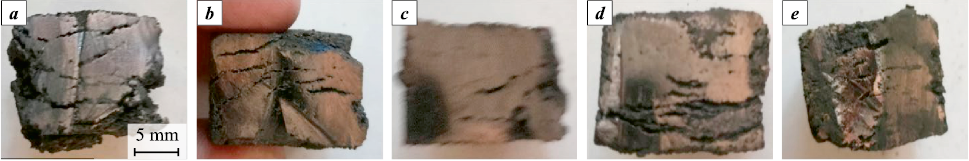

Fig. 2 shows macro-images of polished sections of the synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples produced from the Ti + C SHS charge without Cu addition at different compaction pressures (P). Regardless of the applied pressure, the resulting samples contain numerous unfilled pores, pronounced delamination, and even cracking. At P = 69 MPa, the composite underwent complete destruction during synthesis.

Fig. 2. Macro-images of polished sections of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples |

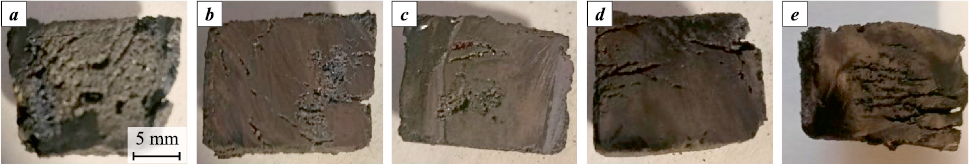

Figs. 3–5 macro-images of polished sections of TiC–Cu cermet samples synthesized from SHS charges containing Cu at different compaction pressures.

Analysis of Fig. 3 shows that even a relatively small amount of copper (0.75 g) in the charge markedly affects the macrostructure of the resulting composites. The 5 % Cu addition significantly improves the infiltration completeness of the thermite copper melt into the synthesized TiC preform. As the compaction pressure increases, the defect morphology changes: at P = 22 MPa, the composite contains a considerable fraction of open pores, whereas higher pressures lead to progressively more complete infiltration across the sample cross-section. However, the nature of defects shifts from pore-dominated to crack-dominated.

Fig. 3. Macro-images of polished sections of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples |

When the Cu addition is increased to 10 %, all samples become infiltrated and exhibit only residual porosity (Fig. 4). At lower compaction pressures, infiltration remains incomplete (Fig. 4, a, b). Numerous small pores and cracks are observed along the periphery of the samples. It is worth noting that at P = 45 MPa the samples show the lowest defect density among all conditions studied in this work, and infiltration occurs throughout the entire TiC preform volume. Further increases in compaction pressure lead to composite delamination and crack formation.

Fig. 4. Macro-images of polished sections of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples |

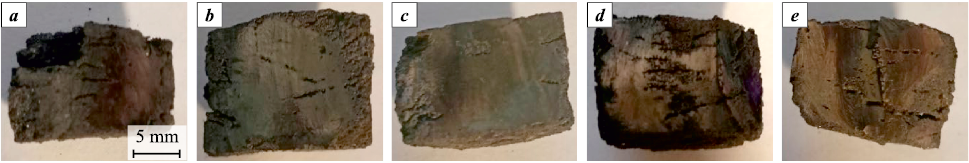

The samples with 15 % Cu exhibit an increased defect density in their macro-structure, accompanied by a change in defect morphology. In the micrographs shown in Fig. 5, individual isolated pores are almost completely absent; instead, the defects appear predominantly as clusters of fine pores arranged in crack-like formations.

Fig. 5. Macro-images of polished sections of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples |

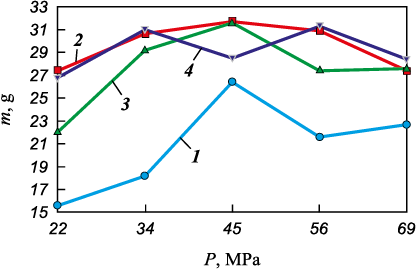

The masses of the synthesized cermet samples obtained under different synthesis conditions – Cu addition to the SHS charge and compaction pressure – are listed in Table 1 and presented graphically in Fig. 6. These data show that at P = 45 MPa all samples demonstrate a distinct mass maximum, indicating the most complete infiltration, particularly for SHS charges containing 5 and 10 % Cu.

Table 1. Dependence of cermet sample mass (g) on synthesis conditions

Fig. 6. Dependence of the mass of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To evaluate the completeness of infiltration, the density of the synthesized cermets was calculated as

ρ = m/V,

where m is the mass and V is the volume of the body. The obtained results are presented in Table 2 and in graphical form in Fig. 7. The data show that the density increases with increasing Cu content in the SHS charge. In addition, a distinct peak of maximum density is observed at 45 MPa for the 10 % Cu addition.

Table 2. Density (ρ, g/cm3) of the synthesized cermet samples

Fig. 7. Dependence of the density of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

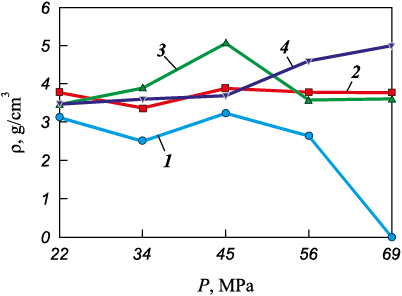

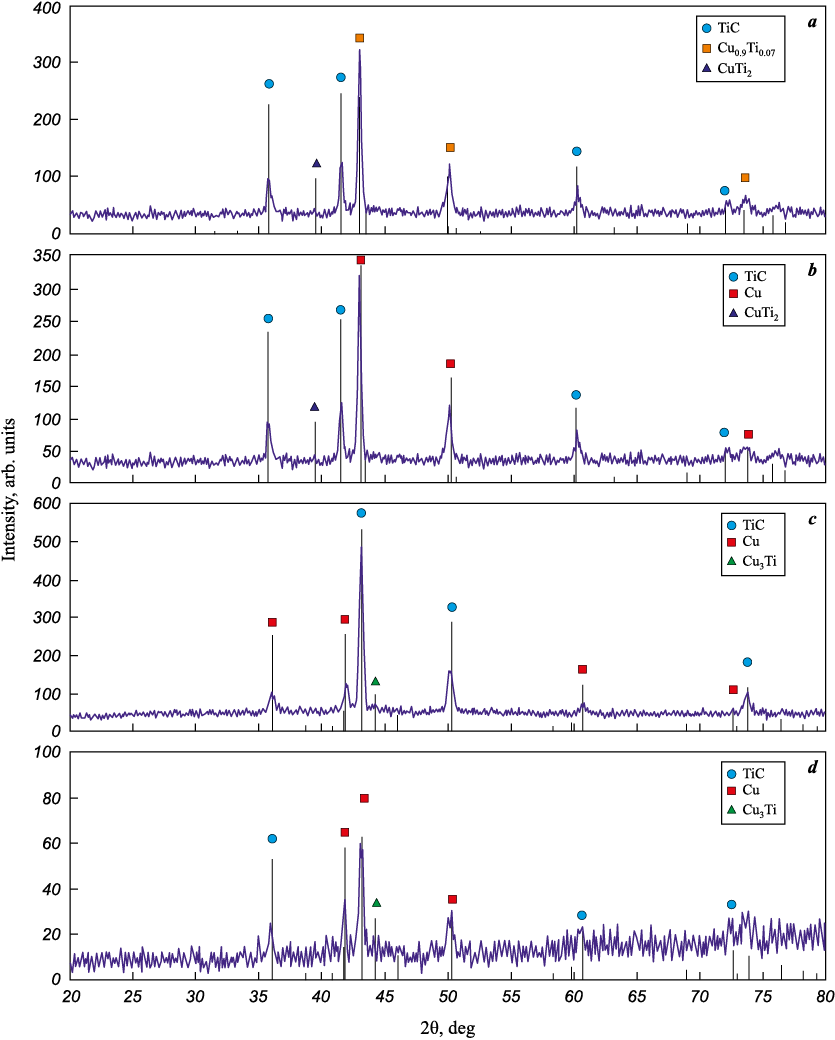

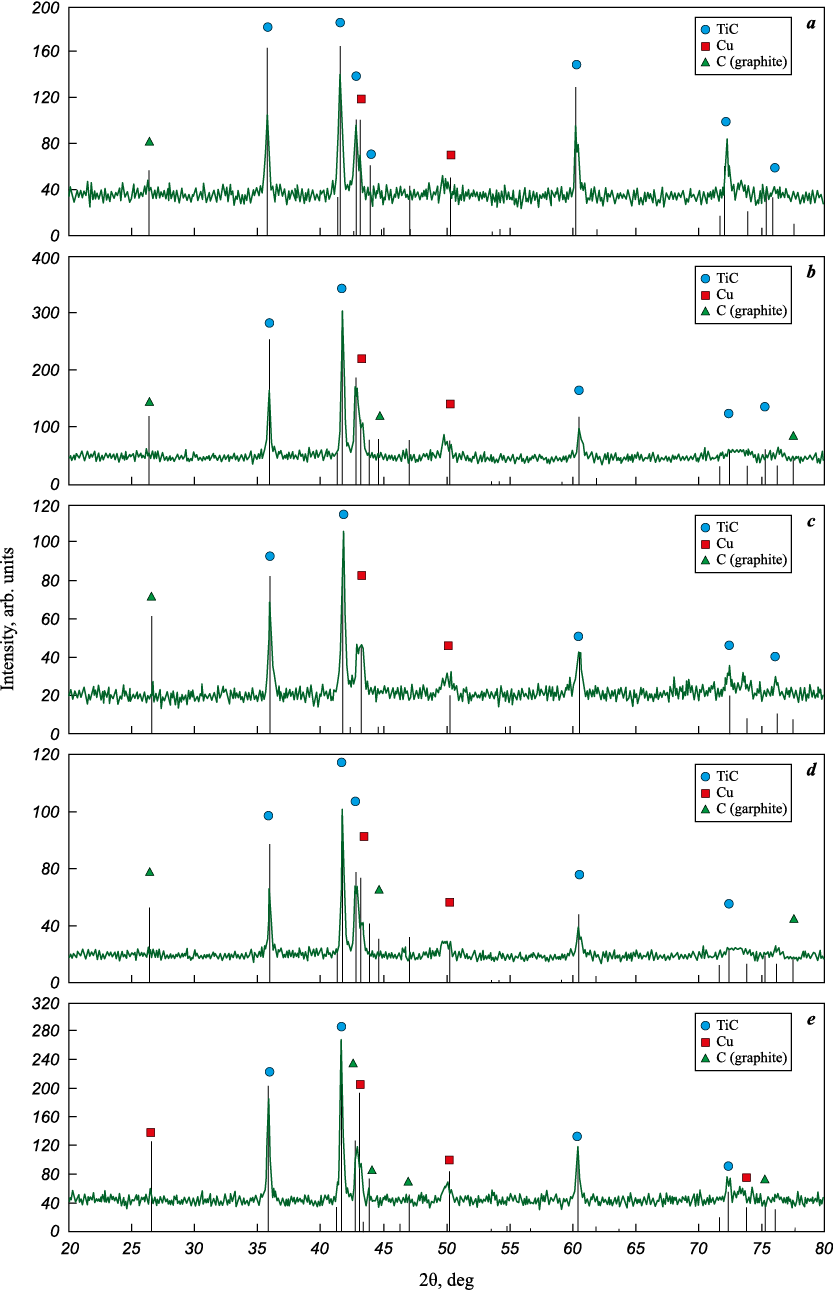

To analyze the phase composition of the obtained TiC–Cu composites, X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed. The corresponding diffraction patterns are shown in Figs. 8–10. All TiC–Cu samples produced from SHS charges without Cu addition contain a significant fraction of Ti–Cu intermetallic compounds, and all diffraction patterns exhibit shifts of Cu peaks, which may indicate stable incorporation of a small amount of Ti in the copper matrix (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Diffraction patterns of synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples obtained from the SHS charge |

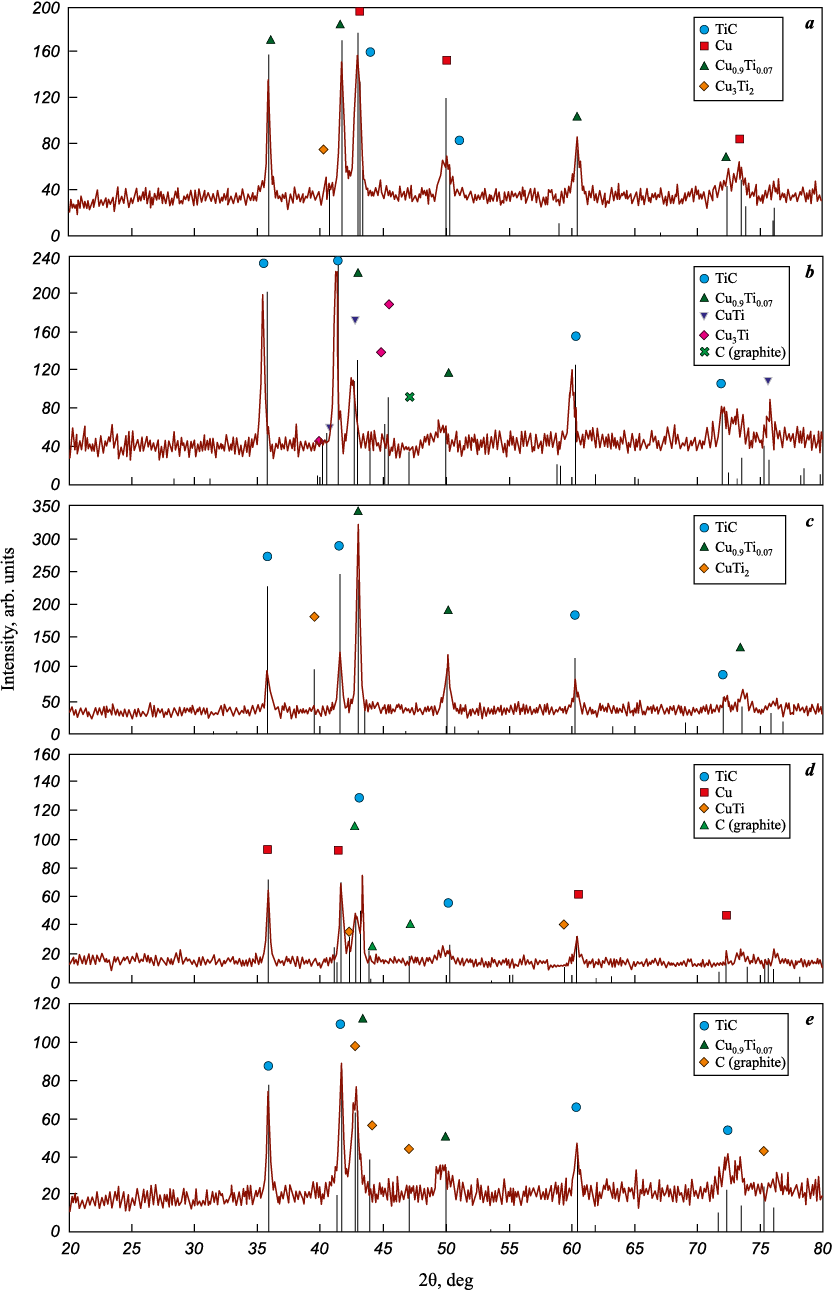

As follows from Fig. 9, the introduction of 5 % Cu into the charge eliminates the Ti–Cu intermetallic peaks on the diffraction patterns. However, peaks of free graphite (Gr) appear. Considering that the carbon phase (carbon black) in the initial SHS charge corresponded to the stoichiometry of TiC, the observed free carbon in the form of graphite should lead to non-stoichiometric titanium carbide TiCx . The shift of the TiC peaks supports this interpretation. The graphite peak may also indicate graphitization of the amorphous carbon black introduced into the reaction mixture. Partial graphitization of carbon black during SHS of titanium carbide was previously reported in SHS–pressing experiments [29], where amorphous carbon transformed into graphitic nanofilms.

Fig. 9. Diffraction patterns of synthesized cermet samples obtained from the SHS charge |

It is also important to note that under the conditions of intensive thermite combustion in air without the use of a special crucible for the metallothermic reaction (Fig. 1), where gravitational phase separation of liquid copper and alumina might not proceed to completion, the presence of Al2O3 in the TiC–Cu cermets was expected. However, XRD data show that none of the synthesized cermet samples contain alumina contamination. This result can be explained by the fact that at high combustion temperatures the relatively low-viscosity thermite copper melt wets the ceramic TiC preform and infiltrates it, whereas the more viscous Al2O3 melt does not wet the preform sufficiently and therefore does not infiltrate [30]. Thus, in this case the phase separation of Cu and Al2O3 produced in the thermite reaction is governed by their strong differences in viscosity and wettability of the TiC.

As seen from Fig. 10, with increasing Cu content in the charge, the SHS process is still initiated despite the expected reduction in exothermicity, leading to TiC formation. At the same time, Ti–Cu intermetallic compounds are generated, accompanied by partial graphitization of the carbon black.

Fig. 10. Diffraction patterns of synthesized cermet samples obtained from the SHS charge |

XRD results for samples with 15 % Cu addition are not shown because they are identical to those presented in Fig. 10).

Based on these observations, it can be concluded that in all examined cases the molten copper completely infiltrates the porous SHS-produced TiC preform. In every experiment, stable combustion of the SHS charge and the formation of the TiC preform were observed. The purest samples – those free of intermetallic inclusions – were obtained with 5 % Cu addition to the Ti + C SHS charge at a compaction pressure of 45 MPa.

To investigate hardness (HB), a TH600 hardness tester (Time Group Inc., China) was used. The results, based on four measurements for each sample, are presented in Table 3. The highest hardness values (95 HB) were achieved at 5 and 10 % Cu additions with a compaction pressure of 34 MPa, whereas at the optimal pressure of 45 MPa and 15 % Cu addition a comparable value of 88.5 HB was reached.

Table 3. Brinell hardness (HB) of the synthesized TiC–Cu cermet samples

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For compression strength (σc ), samples synthesized under optimal conditions (P = 45 MPa) were selected. Samples produced without Cu addition were excluded because of high residual porosity and structural heterogeneity, which significantly reduce strength compared to samples derived from Cu-containing charges. The obtained results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Compressive strength (σc , MPa) of TiC–Cu cermet samples

|

The data clearly show a substantial increase in compressive strength with increasing Cu content in the composite. This is associated with the fact that adding 5–15 % Cu to the Ti + C SHS charge promotes the formation of a more homogeneous SHS-produced TiC preform and ensures more complete infiltration by the thermite copper melt. As a result, structurally more uniform TiC–Cu composites with minimal residual porosity and significantly higher hardness and compressive strength are obtained.

Conclusions

1. The feasibility of synthesizing TiC–Cu composites by combining aluminothermy to produce a copper melt with subsequent SHS initiation to form a porous TiC preform in air without the use of crucible reactors has been demonstrated.

2. It has been established that the copper melt generated by the aluminothermic reaction spontaneously infiltrates the still-hot porous SHS-produced TiC preform, in contrast to alumina, which is also formed during aluminothermy but does not infiltrate and remains outside the TiC preform.

3. Microstructural examination of the TiC–Cu composites showed that the compaction pressure of the Ti + C SHS charge and the addition of copper powder significantly affect the completeness of infiltration by the thermite copper melt. The highest infiltration completeness and density of the TiC–Cu samples (3.89 g/cm3), combined with minimal structural defects, are achieved at 10 wt. % Cu addition to the SHS charge and a compaction pressure of 45 MPa.

4. The hardness of TiC–Cu composites obtained from SHS charges compacted at 45 MPa reaches 88.5 HB for a 15 wt. % Cu addition, which is close to the maximum value of 95 HB observed at P = 34 MPa with 5–10 wt. % Cu.

5. The compressive strength increases markedly with increasing copper content in the initial SHS charge and reaches a maximum value of 414 MPa at 15 wt. % Cu and P = 45 MPa.

References

1. Kumar V., Singh A., Ankit, Gaurav G. A comprehensive review of processing techniques, reinforcement effects, and performance characteristics in copper-based metal matrix composites. Interactions. 2024;245(1):357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10751-024-02200-9

2. Serpova V.M., Nyafkin A.N., Kurbatkina E.I. Hybrid metal composite materials based on copper (review). Trudy VIAM. 2022;1(107):76–87. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.18577/2307-6046-2022-0-1-76-87

3. Suman P., Bannaravuri P.K., Baburao G., Kandavalli S.R., Alam S., Shanthi Raju M., Pulisheru K.S. Integrity on properties of Cu-based composites with the addition of reinforcement: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021;47(19):6609–6613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.05.096

4. Kumar S., Yadav A., Patel V., Nahak B., Kumar A. Mechanical behaviour of SiC particulate reinforced Cu alloy based metal matrix composite. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021;41(2):186–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.08.580

5. Chandrakanth R.G., Rajkumar K., Aravindan S. Fabrication of copper–TiC–graphite hybrid metal matrix composites through microwave processing. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2010;48(5):645–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-009-2474-0

6. Tian J., Shobu K. Hot-pressed AlN-Cu metal matrix composites and their thermal properties. Journal of Materials Science. 2004;39(4):1309–1313. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JMSC.0000013890.01343.0c

7. Shehata F., Fathy A., Abdelhameed M., Moustafa S.F. Preparation and properties of Al2O3 nanoparticle reinforced copper matrix composites by in situ processing. Materials & Design, 2009;30(7):2756–2762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2008.10.005

8. Dong S.J., Zhou Y., Shi Y.W., Chang B.H. Formation of a TiB2-reinforced copper-based composite by mechanical alloying and hot pressing. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2002;33(4):1275–1280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-002-0228-9

9. Samal P., Tarai H., Meher A., Surekha B., Vundavilli P.R. Effect of SiC and WC reinforcements on microstructural and mechanical characteristics of copper alloy-based metal matrix composites using stir casting route. Applied Sciences. 2023;13(3):1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031754

10. Zhan Y., Zhang G. Friction and wear behavior of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC and graphite particles. Tribology Letters. 2004;17(1):91–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TRIL.0000017423.70725.1c

11. Zhang X., Shi C., Liu E. In-situ space-confined synthesis of well-dispersed three-dimensional graphene/carbon nanotube hybrid reinforced copper nanocomposites with balanced strength and ductility. Composites. Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing. 2017;103:178–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.09.010

12. Kato H., Takama M., Iwai Y., Washida K., Sasaki Y. Wear and mechanical properties of sintered copper–tin composites containing graphite or molybdenum disulfide. Wear. 2003;255(1):573–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1648(03)00072-3

13. Li L., Wong Y.S., Fuh J.Y., Lu L. Effect of TiC in copper–tungsten electrodes on EDM performance. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2001;113(1):563–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-0136(01)00622-7

14. Zarrinfar N., Kennedy A.R., Shipway P.H. Reaction synthesis of Cu–TiCx master-alloys for the production of copper-based composites. Scripta Materialia. 2004;50(7):949–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2004.01.007

15. Frage N., Froumin N., Dariel M.P. Wetting of TiC by non-reactive liquid metals. Acta Materialia. 2002;50(2): 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(01)00349-4

16. Froumin N., Frage N., Polak M., Dariel M.P. Wetting phenomena in the TiC/(Cu–Al) system. Acta Materialia. 2000;48(7):1435–1441. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(99)00452-8

17. Amosov A.P., Borovinskaya I.P., Merzhanov A.G. Powder technology of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of materials. Moscow: Mashinostroenie-1, 2007. 567 p. (In Russ.).

18. Alabushev V.A., Rozhkov A.S. Method of obtaining products from composite materials based on titanium carbide: Patent 1338209 (RF). 1995.

19. Tsikarev V.G., Filippenkov A.A., Filippov M.A., Alabushev A.V., Sharapova V.A. The experience of obtaining composite materials of the Ti–Cu–C system by the SHS process. Powder Metallurgy and Functional Coatings. 2021;(4):4–11. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2021-4-11

20. Amosov A., Amosov E., Latukhin E., Kichaev P., Umerov E. Producing TiC–Al cermet by combustion synthesis of TiC porous skeleton with spontaneous infiltration by aluminum melt. In: Proc. of 2020 7th International Congress on Energy Fluxes and Radiation Effects. IEEE, 2020. P. 1057–1062. https://doi.org/10.1109/EFRE47760.2020.9241903

21. Amosov A.P., Latukhin E.I., Umerov E.R. Applying infiltration processes and self-propagating high-temperature synthesis for manufacturing cermets: А review. Russian Journal of Non-Ferrous Metals. 2022; 63(1):81–100. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821222010047

22. Umerov E., Amosov A., Latukhin E., Kiran K.U., Choi H., Saha S., Roy S. fabrication of MAX-phase composites by novel combustion synthesis and spontaneous metal melt infiltration: Structure and tribological behaviors. Advanced Engineering Materials. 2024;26(8):2301792. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.202301792

23. Karakich E.A., Samboruk A.R., Maidan D.A. Thermite welding. Sovremennye materialy, tekhnika i tekhnologii. 2021;1(34):63–67. (In Russ.).

24. Merzhanov A.G. Thermally coupled processes of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Doklady Physical Chemistry. 2010;434(2):159–162. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0012501610100015

25. Kharatyan S.L., Merzhanov A.G. Coupled SHS reactions as a useful tool for synthesis of materials: An overview. International Journal of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. 2012;21(1):59–73. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1061386212010074

26. Amosov A.P., Samboruk A.R., Yatsenko I.V., Yatsenko V.V. TiC–Fe powders by coupled SHS reactions: An overview. International Journal of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. 2019;28(1):10–17. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1061386219010023

27. Karakich E.A., Amosov A.P. Designing equipment for SHS thermite synthesis. Sovremennye materialy, tekhnika i tekhnologii. 2024;1(52):9–15. (In Russ.).

28. Karakich E.A., Latukhin E.I., Umerov E.R., Amosov A.P. Comparison of X-ray diffraction data of samples of TiC–Cu cermets synthesized under various charge pressing conditions. In: Modern perspective development of science, equipment and technologies. Collection of scientific articles of the 2nd International Scientific and Technical Conference. Kursk: CJSC “University Book”, 2024. Р. 175–179.

29. Shcherbakov V.A., Grydunov A.N., Karpov A.V., Sachkova N.V., Sychev A.E. Self-expanding high-temperature synthesis of TiC + xC composites. Neorganicheskie materialy. 2020;56(6):598–602. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.31857/s0002337x20060111

30. Sanin V.N., Yukhvid V.I. Centrifugation-driven melt infiltration in high-temperature layered systems. Inorganic Materials. 2005;41(3):247–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10789-005-0118-9

About the Authors

E. A. KarakichRussian Federation

Egor A. Karakich – Post-graduate student, Junior Researcher of the Department of Metal Science, Powder Metallurgy, and Nanomaterials (MSPMN)

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

E. R. Umerov

Russian Federation

Emil R. Umerov – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Leading Researcher of the Department of MSPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

V. A. Novikov

Russian Federation

Vladislav A. Novikov – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor of the Department of MSPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

P. E. Kichaev

Russian Federation

Evgeniy P. Kichaev – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Associate Professor of the Department of Mechanics

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

A. P. Amosov

Russian Federation

Alexander P. Amosov – Dr. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Head of the Department of MSPMN

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

Review

For citations:

Karakich E.A., Umerov E.R., Novikov V.A., Kichaev P.E., Amosov A.P. Effect of Cu additions and SHS charge compaction pressure on thermite-copper infiltration and the macrostructure of synthesized TiC–Cu cermets. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):52-64. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-52-0