Scroll to:

Mechanisms of failure in anti-corrosion polymer coatings on metallic surfaces of oilfield pipelines: Review

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-65-82

Abstract

Corrosion is one of the primary causes of failure in oil and gas equipment, affecting not only its service life but also operational safety. In the Russian Federation, crude-oil production is increasingly complicated by the high water content of produced fluids, which significantly accelerates corrosion processes. The use of internal polymer coatings in pipelines partly mitigates this problem; however, the proportion of corrosion-related failures remains high. Effective protection of oil pipelines using polymer coatings requires a clear understanding of their degradation mechanisms, including under conditions that closely approximate field operation. Such understanding enables the development of effective solutions that help maintain the operating stock of oil wells in serviceable condition. This work summarizes the principal mechanisms of degradation of polymer coatings on metallic surfaces, including under exposure to aggressive environments. The key factors governing coating failure in oil pipelines are identified: diffusion and absorption of water molecules within the polymer matrix; disruption of molecular interactions in the polymer network; delamination due to loss of adhesion between the coating and the metal; interfacial corrosion; cathodic delamination; blister formation; and erosion-driven damage. The study presents results of the examination of various epoxy–novolac-based anticorrosion coatings removed from pipelines after field service and provides representative images of coatings at different degradation stages. The aim of the work was to consolidate current knowledge on the degradation mechanisms of polymer coatings on metals under diverse conditions and to refine the staged description of coating degradation in oil pipelines.

Keywords

For citations:

Yudin P.E., Lozhkomoev A.S. Mechanisms of failure in anti-corrosion polymer coatings on metallic surfaces of oilfield pipelines: Review. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):65-82. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-65-82

Introduction

All polymers are, in principle, permeable to well fluids encountered during oil production, and this permeability ultimately results in corrosion and delamination of internal polymer coatings (IPCs) used in oilfield pipelines [1]. The permeability of water, oxygen, and electrolyte ions through the coating is a fundamental characteristic governing the progression of coating degradation and the subsequent corrosion of pipeline steel [2]. The failure mechanism of IPCs includes:

• ingress of water and ions into the coating, where water diffuses through the polymer matrix and initiates changes in its properties;

• chemical degradation of the polymer molecular structure, in which water cleaves reactive sites within the epoxy network, causing hydrolysis-induced chain scission;

• accumulation of water within micropores of the coating, forming pathways for ion transport and ultimately leading to coating delamination from the metal surface [2].

Water absorption (hydration) within epoxy coatings is one of the primary causes of failure in pipeline coating systems [3].The uptake of water softens and plasticizes the polymer network, promotes blister formation, cracking, and localized delamination of the epoxy layer. During prolonged exposure to water and aggressive chemical species, water molecules displace polar interfacial bonds between the coating and steel, weakening adhesion. Underfilm corrosion represents the final stage of degradation, where the combined effects of adhesion loss and osmotic pressure cause cracking and delamination, resulting in coating failure and a substantial reduction in pipeline service life [3].

The corrosion process is governed by anodic and cathodic reactions at the metal–polymer interface [4; 5]. Cathodic reactions at the metal surface generate hydroxide ions, producing a highly alkaline environment [6; 7] that can raise the local pH to values above 14 beneath the coating near the delamination front [7]. Cathodic delamination may therefore arise from:

– electrochemical reduction of the oxide layer [8];

– alkaline hydrolysis [9] or electrochemical degradation [10] of the interfacial polymer region responsible for adhesion;

– alkaline breakdown of interfacial bonds [8].

The interfacial polymer layer is also degraded by free radicals generated through Fenton-type reactions involving Fe2+ and H2O2 or organic peroxides [11; 12]. These peroxide intermediates form during oxygen reduction and react with iron cations in the electrolyte near the metal–polymer interface. Radical-driven degradation weakens interfacial adhesion and accelerates delamination [11; 12]. Cathodic polarization additionally promotes molecular hydrogen evolution at the metal surface [13; 14]. The evolution of molecular hydrogen gas at the metal–polymer interface can generate high interfacial pressures and additional mechanical stresses within the delamination zone. This effect is supported by the established correlation between the electrolytic hydrogen uptake current in the metal and the rate of cathodic delamination [13].

This review summarizes the general mechanisms of polymer-coating degradation on metallic surfaces in atmospheric environments or ionized water – where oxygen acts as the primary corrosive agent. It further examines the behavior of internal anti-corrosion coatings used in gathering pipelines, water lines, and tubing strings, and presents an updated staging model for IPC degradation in oil pipelines.

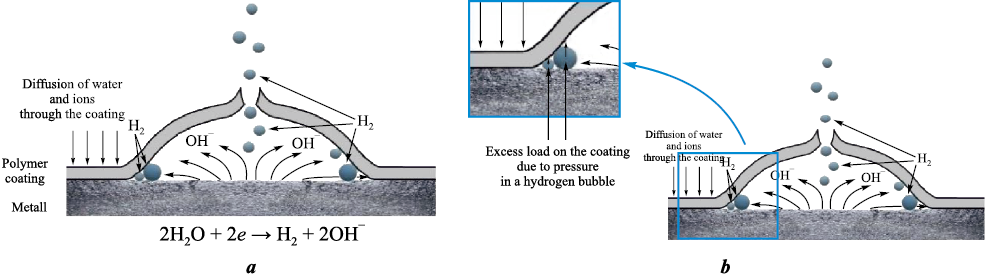

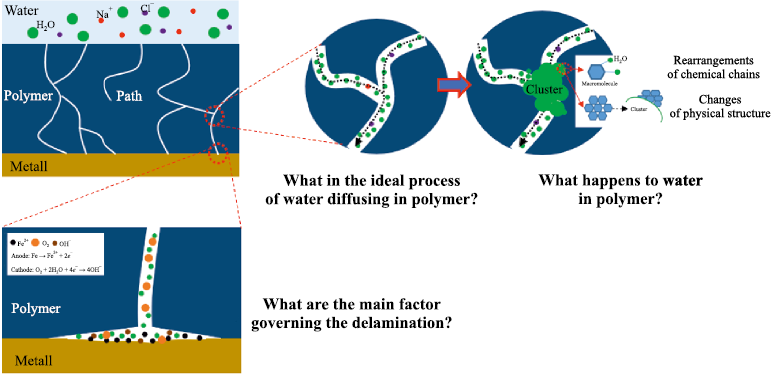

Cathodic delamination of coatings

A schematic representation of cathodic delamination is presented in [15] (Fig. 1), based on an experimental study of the degradation of a polybutadiene coating on steel exposed to a 0.5 M NaCl solution under a cathodic potential of –1.5 V for 1000 h [8]. At the edge of the delaminated region, a pronounced decrease in oxide-film thickness was observed compared with the central area [8]. The increase in pH at the delamination front promotes dissolution of the oxide layer; however, as the interfacial gap (the distance between the metal surface and the lifted coating) increases, the pH gradually decreases and the oxide layer thickensagain.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the processes occurring in a defective polymer coating |

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis [8] within the delaminated region revealed a metallic surface beneath the coating that was essentially free of oxide. According to the authors, this indicates that the surface oxide layer undergoes either reduction or dissolution. This process results in intraphase degradation of interfacial bonds and leads to interfacial separation along the metal/oxide boundary, with the oxide layer being removed together with the delaminated coating. Outside the interfacial separation zone, the coating detaches cleanly from the metal substrate without cohesive damage [8].

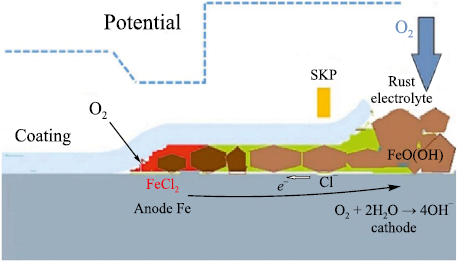

Anodic corrosion

Filiform corrosion, a form of anodic underfilm corrosion, has been observed on metals with polymer coatings exposed to a humid atmosphere, the aggressiveness of which is enhanced by artificial or natural contaminants such as sulfur dioxide or chlorides [16; 17]. This type of corrosion (Fig. 2) typically initiates at discontinuities in regions containing porosity and voids, mechanical defects, or areas of reduced coating thickness. Filiform corrosion is characterized by linear propagation paths, where local accumulation of water at the metal/coating interface triggers electrochemical processes [18; 19]. Localized anodic reactions on the steel are coupled with oxygen reduction, which in turn promotes cathodic degradation of adhesion at the interface.

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of anodic delamination |

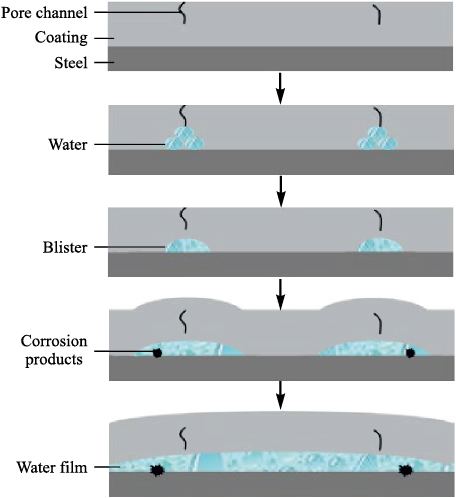

Diffusion of reactants

through polymer coatings

Fig. 3 illustrates the stages of coating delamination under high hydrostatic pressure as proposed in [20]. In an epoxy-varnish coating, the applied pressure significantly accelerates the diffusion of water toward the coating–substrate interface and leads to the formation of numerous small, water-filled blisters.

Fig. 3. Schematic representation of the coating-failure process |

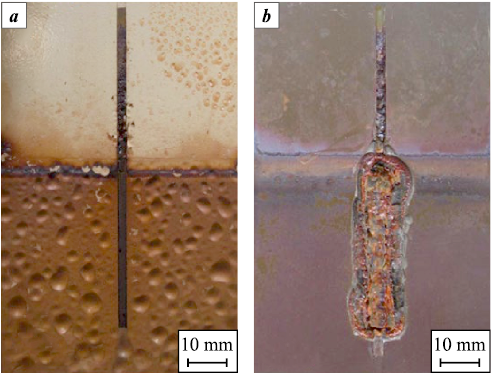

One of the most important degradation mechanisms is coating aging, which results in a loss of barrier performance and deterioration of mechanical properties. Aging occurs under the combined influence of elevated temperature, chemically aggressive species, pressure, and mechanical loading [21]. Another critical failure mechanism is blister formation during decompression. As described in [21], gases penetrate the pores of the material at high pressure; when the pressure is rapidly reduced, the dissolved gases expand, generating blisters within the coating and causing its failure (Fig. 4, a). Corrosion also develops at sites where the coating is mechanically damaged (Fig. 4, b). In such cases, the base metal of the pipe is directly exposed to the aggressive environment, leading to active corrosion. When defects are present, the rate of corrosion progresses with similar intensity regardless of the coating type [21].

Fig. 4. Coating failure after corrosion autoclave testing [21] |

The authors of [22] nvestigated the effect of prolonged exposure (85 weeks) to hot water at 65 °C on epoxy powder barrier coatings used to protect metallic surfaces, including components of oil and gas equipment. It was shown that degradation of the coating begins after only 8 weeks, while oxidation of the substrate becomes noticeable after 182 days. Adhesion-strength measurements demonstrated that the bonding strength of the coatings decreases rapidly due to water-induced plasticization, but subsequently exhibits a slight recovery attributed to secondary crosslinking of the epoxy network [22].

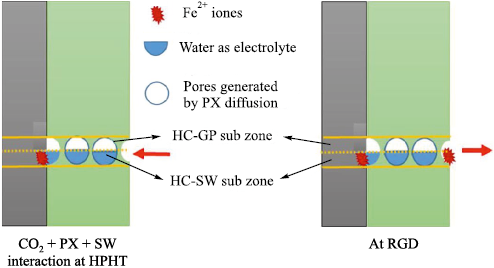

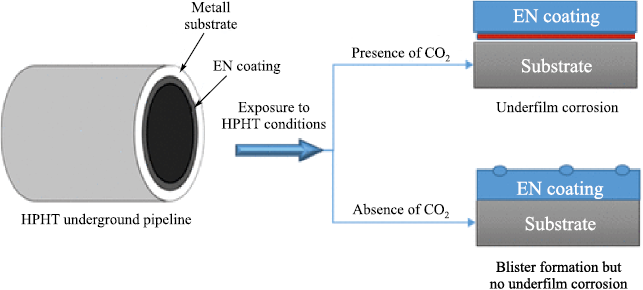

A study presented in [23] examined the degradation mechanisms of coatings based on amine-cured epoxy novolac (EN) and bisphenol-F (BPF) resins under high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) conditions. The coatings were subjected to autoclave testing. It was established that the degradation mechanisms of EN and BPF protective coatings under HPHT conditions are governed by the combined action of gas, hydrocarbon, and aqueous phases and their joint effects on the polymer structure and the substrate. In the gas phase, consisting of nitrogen and carbon dioxide, the coatings remain unchanged because no significant interaction or physical damage occurs. However, contact of the coating surface with hydrocarbons (p-xylene) results in solvent diffusion into the polymer matrix, which increases the free volume within the coating layer. Fig. 5 illustrates the mechanisms of coating degradation under HPHT exposure to p-xylene during autoclave conditioning, as well as during pressure release under decompression [23].

Fig. 5. Water ingress through the coating toward the metal |

The study reported in [24], which involved simultaneous exposure to three phases (a gas phase, a hydrocarbon liquid phase, and mineralized water), investigated the influence of carbon dioxide (CO2 ) present in the gas phase under HPHT conditions on the degradation of amine-cured epoxy novolac (EN) coatings. It was established that the combined action of the gas, hydrocarbon, and aqueous phases deteriorates the coating performance and leads to underfilm corrosion. When each phase was applied separately under low-pressure conditions, the EN network remained intact and essentially impermeable. However, in regions exposed to hydrocarbons, the joint action of p-xylene and CO2 at elevated pressure and temperature causes a reduction in the glass-transition temperature, followed by softening of the EN network. This softening allows dissolved CO2 to diffuse into the EN structure, forming microscopic voids at the coating surface (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Mechanisms by which the hydrocarbon and aqueous phases affect |

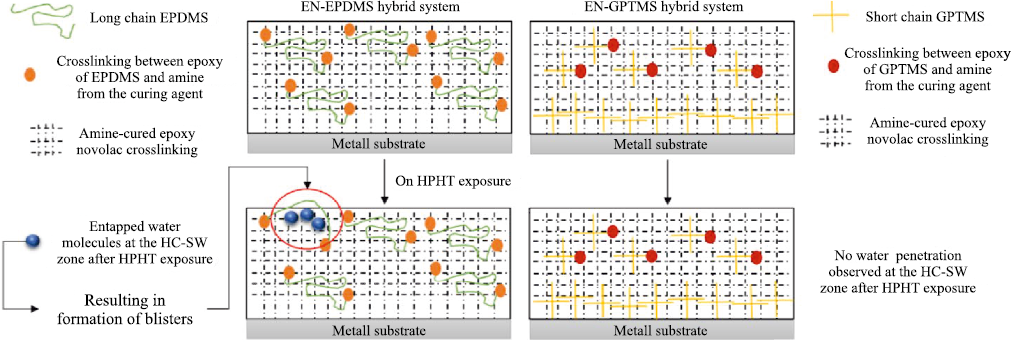

Comparative autoclave tests under high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) conditions were carried out in [25] or epoxy–siloxane hybrid coatings. These coatings were shown to outperform EN-based systems, which soften upon exposure to hydrocarbons (such as p-xylene), resulting in a reduction in glass-transition temperature and an accelerated diffusion of gases and ions.

The long polymer chains in siloxane-based coatings (EN-EPDMS) promote the uptake of water molecules, especially under high pressure. Such coatings tend to form unruptured blisters during rapid pressure release. In contrast, the coating modified with the short-chain 3-glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (EN-GPTMS) exhibited high resistance to decompression (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Schematic illustration of crosslinking in EN-EPDMS and EN-GPTMS coatings |

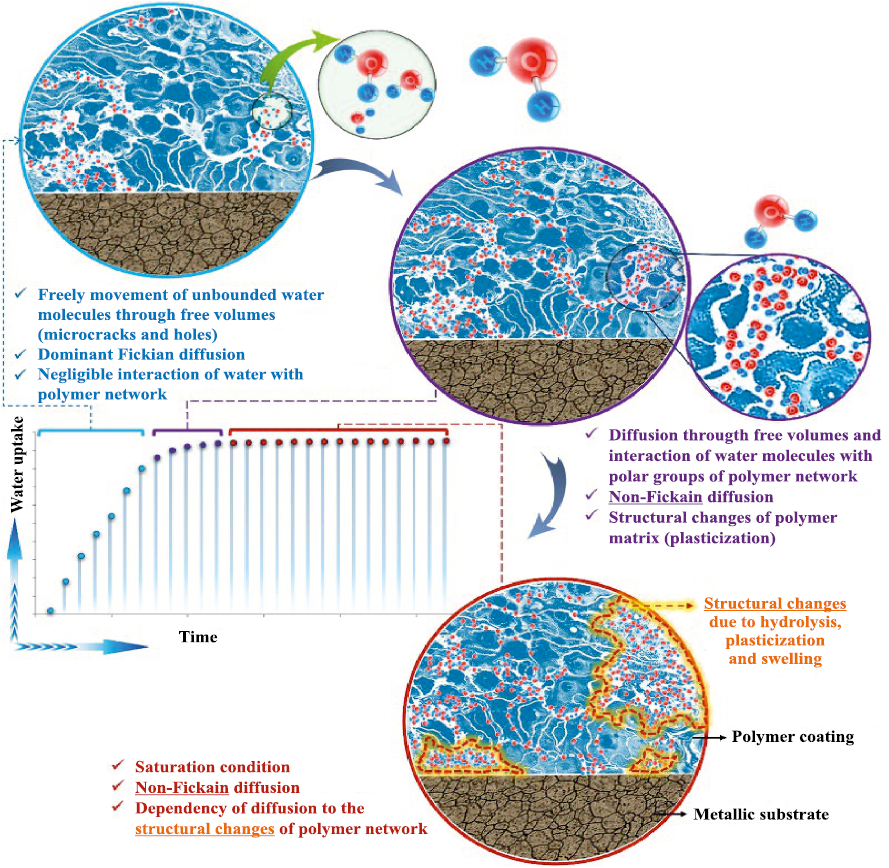

Under the assumption that the coating remains intact and free of defects or inclusions, it can therefore be concluded that the primary initiating factor for coating degradation and the onset of corrosion is the diffusion of reactive species through the polymer layer (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Schematic illustration of changes in water uptake in polymer coatings |

However, as noted by the authors of the review [26], many open questions remain regarding the swelling behavior of polymers and the complexity of describing diffusion processes that deviate from ideal Fickian diffusion (Fick’s second law), among other issues (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Schematic representation of water diffusion through a polymer layer |

Overall, the degradation of a polymer coating is governed by the following processes and/or their combination.

• Diffusion and absorption of water molecules within the polymer matrix. These processes are influenced by surface topography, polymer structure, and environmental conditions. Free volume and microcracks within the coating structure provide pathways for the diffusion of water molecules, which may follow Fickian, non-Fickian, and/or capillary diffusion regimes. As they move from the external coating surface toward the coating/metal interface, water molecules may either migrate freely or interact with polar segments of the polymer network. Water absorption by the polymer leads to structural instability of the polymer network (plasticization), promoting volumetric expansion, interfacial separation, and erosion of the coating [27–30].

• Disruption of van der Waals and hydrogen bonds within the polymer network as a result of interactions between water molecules and polar segments of the polymer chain, which causes anisotropic expansion of the network. These volumetric changes and the associated stresses can irreversibly alter the coating microstructure, leading to the initiation and/or growth of microcracks within the coating and at the coating/metal interface [31–34].

• Fragmentation of polymer chains due to hydrolytic degradation of coatings containing hydrolysable bonds. In addition to hydrolysis of the polymer matrix, dissolution of coating components (such as pigments and additives) may occur, resulting in mass loss and structural changes. The hydrolysis process can further accelerate polymer degradation by altering the local pH in regions surrounding the reactive sites [35–37].

• Delamination associated with loss of adhesion, driven by damage to molecular bonds between the coating and the metal, disruption of thermodynamic equilibrium at the metal–polymer interface, and the breakdown of mechanical interlocking and/or the development of osmotic pressure. Delamination is initiated by the permeation of water molecules through the coating to the metallic substrate, thereby compromising coating integrity and accelerating adhesion loss. Typically, delamination is preceded by plasticization and swelling of the coating, as well as changes in interfacial chemistry [38–41].

• Interfacial delamination caused by corrosion at the metal–coating interface. Variations in pH within the interfacial region disturb the thermodynamic equilibrium established by Lewis acid–base interactions, thereby reducing adhesion strength [18]. Corrosion at the metal/coating interface disrupts mechanical interlocking between the coating and the metallic substrate, further weakening adhesion. The accumulation of corrosion products in the interfacial gap generates mechanical stresses due to expansive forces (for example, the formation and growth of rust) [42]. Moreover, the hygroscopic nature of rust enhances moisture uptake, leading to dimensional changes and additional mechanical stresses within the coating. These stresses promote interfacial separation and cracking. Lateral expansion of the separated coating region, caused by growth of corrosion products, can also lead to blister formation [43].

• Cathodic delamination of polymer coatings, which is driven by the alkaline environment generated by cathodic reactions at the metal–polymer interface. As a result, the thermodynamic equilibrium at the interface is disrupted: alkaline species dissolve the thin oxide layer on the metal and induce chemical degradation of the polymer via alkaline hydrolysis and reactive intermediates. This process also promotes substrate corrosion by disturbing the local charge balance and facilitating the transport of charged species. Ultimately, these mechanisms undermine the adhesion forces between the coating and the substrate [39; 44–46].

• Blister-induced delamination of the coating arises from water uptake and electrochemical reactions. The accumulation of water and dissolved species at the metal–polymer interface, together with the resulting osmotic pressure and mechanical stresses, reduces the adhesion of the coating to the metallic substrate and leads to interfacial delamination [47–52].

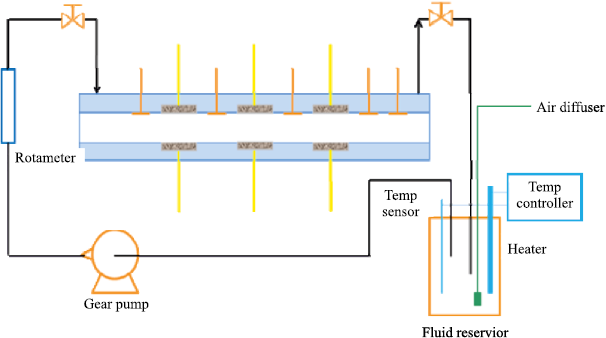

Erosion–corrosion processes

The processes described above, whose combined action leads to degradation of the protective polymer coating, proceed at a substantially accelerated rate when the coating is additionally exposed to flowing fluid during service. In [53], a comparison was made between the deterioration of barrier properties under flow conditions and under static immersion, using an experimental setup whose schematic arrangement is shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Schematic diagram of the setup used to simulate |

The barrier properties of the coating during testing were evaluated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The EIS measurements showed that the impedance modulus of the coating decreases much more significantly under flow, indicating that fluid motion along the protective coating accelerates water ingress into the coating [53]. A similar conclusion – that degradation of an organic coating accelerates when immersed in two different working fluids (DI water and 3.5 wt. % NaCl solution) under laminar-flow conditions compared with static immersion – was also reported by the authors of [54].

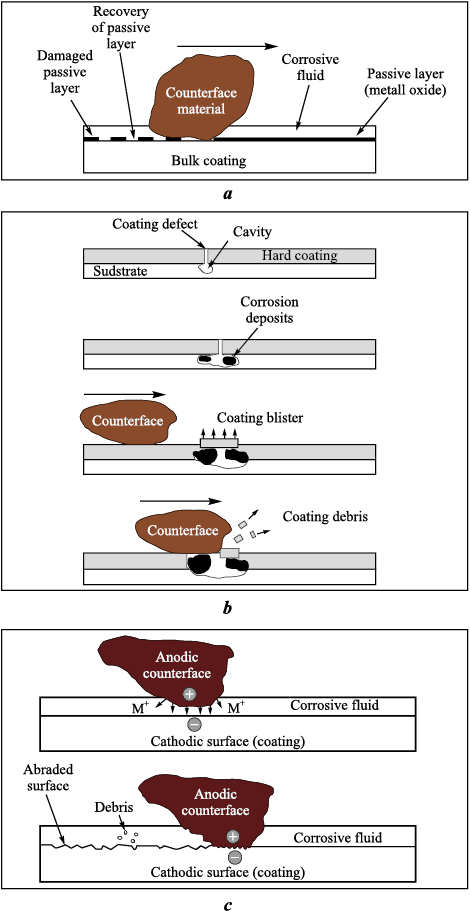

A review presented in [55] summarized existing research on tribocorrosion of coatings, i.e., their behavior under simultaneous action of erosive wear and corrosion. Under erosive flow, the authors distinguish three coating-damage mechanisms:

– surface damage, in which a defect in the passive film triggers repassivation and film reconstruction on the coating surface (Fig. 11, a):

– corrosive wear of hard coatings on metallic substrates, leading to the formation of pits and blistering of the protective coating, followed by mechanical damage and delamination (Fig. 11, b);

– abrasive action on the coating surface caused by the potential difference between the metallic substrate beneath the coating and entrained abrasive particles, which accelerates surface wear (Fig. 11, c).

Fig. 11. Three coating–failure mechanisms under erosive conditions [55] |

In [56], the authors described the degradation mechanism of protective epoxy–novolac coatings exposed to erosion–corrosion. At the first stage, erosive attack produces microcracks exclusively around filler particles. These microcracks create a porous structure that allows the electrolyte to gradually penetrate deeper into the coating. At this stage, however, the coating still maintains sufficient barrier performance to prevent corrosion initiation.

At the second stage, the cracks begin to widen, and the barrier properties of the coating weaken under aggressive conditions (high temperature, low pH, presence of CO2 and chlorides). The electrolyte penetrates further and reaches the metal–polymer interface. As a result, local corrosion initiates and produces corrosion products (iron oxides) within the pores of the coating. This decreases the coating resistance, as detected by electrochemical measurements.

At the third stage, the mechanical integrity of the coating is severely compromised. As underfilm corrosion continues to deepen and spread, the coating delaminates and its structure becomes increasingly porous. As a result, the access of aggressive species to the metallic substrate increases, leading to the initiation of new corrosion sites, and the coating ultimately loses its barrier functionality. All three stages of coating degradation are shown in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12. Stages of polymer-coating degradation under erosive wear, |

Thus, the principal stages and regularities of polymer-coating degradation under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions, as well as under exposure to abrasive particles, have been examined. In most cases, the studies were conducted in atmospheric environments or in ionized water, where oxygen is the predominant corrosion-active species.

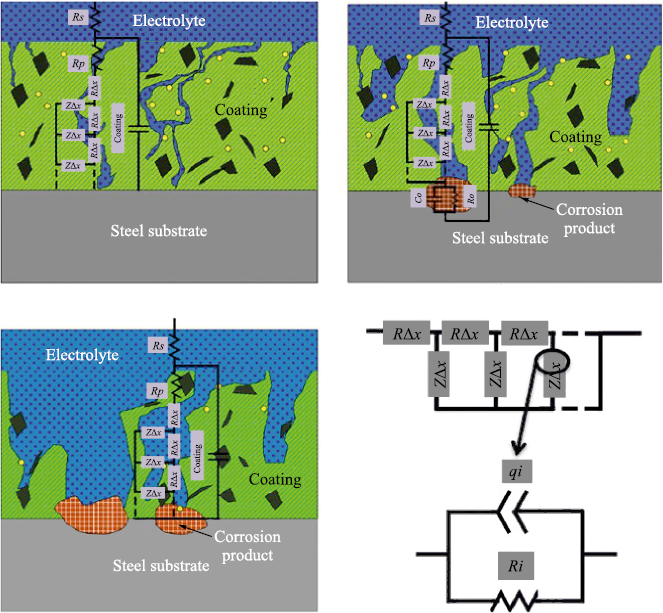

Degradation of internal anticorrosion coatings

in oil pipelines

A review of degradation mechanisms of internal anticorrosion coatings (IACCs) used in oil-gathering collectors, water pipelines, and production tubing strings was previously carried out in [57]. All coatings examined were based on epoxy–novolac systems with different ratios of epoxy film-forming components to novolac resin. Powder coatings were applied by electrostatic spraying, whereas liquid coatings were applied using airless spraying followed by drying or polymerization.

Several processes occur simultaneously within the coating: diffusion of corrosion-active species, degradation of interfacial adhesion, and destructive changes within the polymer matrix that lead to a reduction of cohesive strength. The intensity of these processes depends strongly on temperature and increases sharply as the temperature approaches the glass-transition temperature (Тg) (taking into account its depression caused by water uptake). Therefore, the behavior of these coatings must be considered specifically in their glassy state [58].

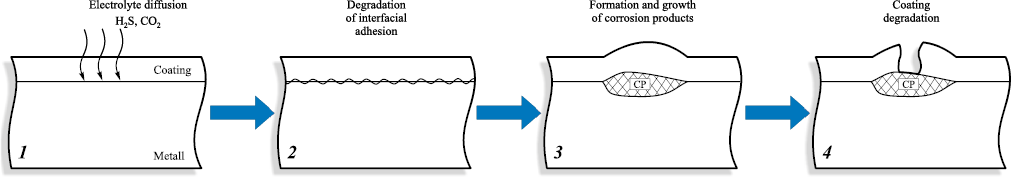

Fig. 13. Staged degradation process of internal protective coatings |

At the present stage of research, coating degradation can be represented by the following sequence (Fig. 13). In the first stage, the polymer undergoes water uptake, accompanied by significant changes in its physical and mechanical properties: Tg decreases by approximately 30 °C at 1.5 wt. % water uptake, while tensile strength decreases by about 20 % [58]. This initial stage proceeds relatively rapidly and can be described by the diffusion equation [26]:

\[q(t) = 1 - \frac{8}{{{\pi ^2}}}\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {\frac{1}{{{{(2n + 1)}^2}}}} \exp \left\{ { - \frac{{{{(2n + 1)}^2}{\pi ^2}D}}{{4{l^2}}}t} \right\},\]

where q(t) is the average concentration of the penetrant across the polymer layer at time t, s; D is the diffusion coefficient for a constant source into a polymer layer of thickness l, cm2/s.

The values of D lie in the range of 1.0·10–9 to 5.0·10–8 cm2/s and depend on the chemical composition of the film-forming component and curing agent, the degree of crosslinking, the type and loading of fillers, as well as the pressure and temperature of the environment.

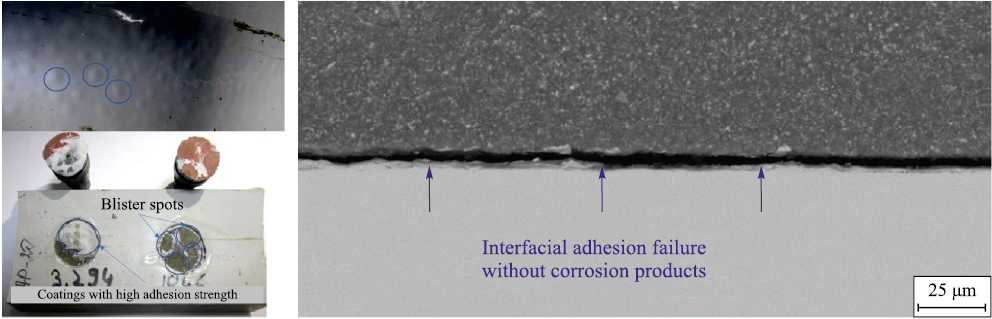

At the second stage, the coating undergoes degradation of interfacial adhesion, which is typically localized and appears as spots with a diameter of approximately ten coating-thicknesses (Fig. 14). This process is prolonged when the coating operates at temperatures below the wet glass-transition temperature (wet Tg) of the polymer and when no application defects are present. The key durability criteria include the initial adhesion strength, the diffusion coefficient, and the coating’s resistance to chemical and physical degradation under service conditions – i.e., the retention of intrinsic coating properties that determine its barrier performance. For example, destructive changes in the polymer structure may produce microcracks that enable not only electrolyte diffusion but full mass transport through the coating.

Fig. 14. Localized blistering of the coating after service (2nd degradation stage) |

During failure analysis of internal polymer coatings, it is often found that a significant reduction in service life results from violations introduced either during application or during operation. A common example illustrating how application technology influences the durability of internal coatings is the frequent occurrence of defects at the ends of production tubing. The application of coatings to tubing ends involves specific operations – make-up of the coupling and cleaning of the tube end and threads from factory lubricant (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Appearance of damage to the internal coating of production tubing |

Conventional removal of lubricant by solvent cleaning and mechanical treatment is often incomplete, resulting in localized blistering and coating failure, even though the coating remains intact over the rest of the pipe surface (Fig. 16). In practice, complete removal of lubricant is reliably achieved only by high-temperature treatment (furnace heating or laser-based heat treatment). Characteristic features of this type of failure are its localization within approximately 100 mm of the pipe end and the presence of large blisters caused by the lack of adhesion in this region.

Fig. 16. Appearance of the internal coating of production tubing, Ø73×5.5 mm |

In this case, overheating is associated with operation at temperatures above the wet-state Tg of the coating. Visually, this failure mode differs little from the normal degradation mechanism; however, the service life may be reduced by more than a factor of ten under elevated-temperature operation.

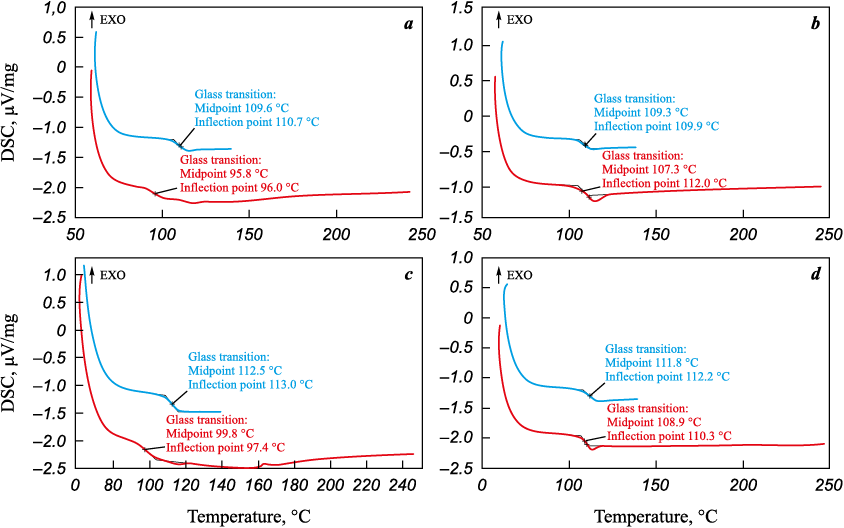

The thermokinetic characteristics of the internal coating were determined in order to assess the degree of cure of the powder-based material using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Tests were carried out on specimens before and after conditioning at 90 °C for 24 h to remove moisture from the coating. The corresponding results are summarized in the table, and the DSC thermograms of the coating material are presented in Fig. 17.

Results of determining the degree of coating curing

Fig. 17. DSC thermograms of the coating specimens: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Based on the test results, the observed difference between the glass-transition temperatures determined in the first and second heating cycles for the as-received specimens is +13.8 and +12.7 °C, respectively, whereas after conditioning the difference decreases to +1.5 and +2.9 °C. This indicates that the coating absorbs moisture during service, which is a typical process for polymeric materials [58]. The absence of a curing peak in the DSC curves confirms that polymerization of the coating had been completed. The Tg values after conditioning (111–113 °C) match those of the as-received coating, demonstrating that no thermo-oxidative degradation occurred.

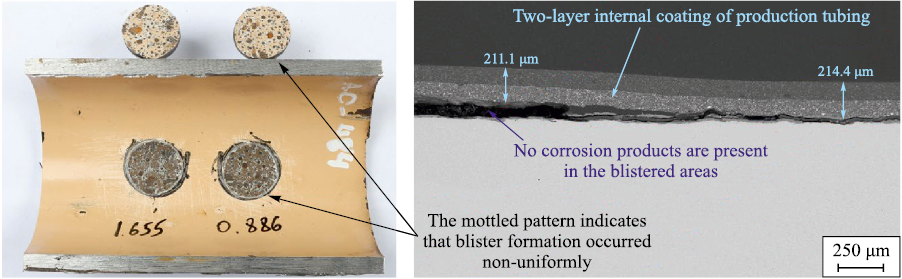

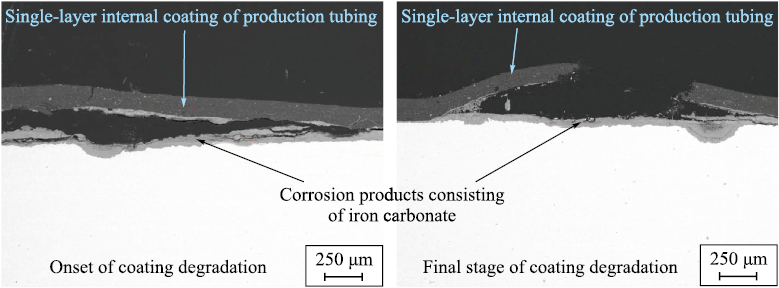

The third degradation stage is governed by the growth of corrosion products and depends on the diffusion coefficient and the corrosion resistance of the steel. This is a long-term process, and its duration is determined not only by the properties of the environment and the coating but also by the absence of mechanical loading on the internal coating, which could otherwise rupture the blister (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. A typical example of the appearance and structure of the coating at the third destruction stage |

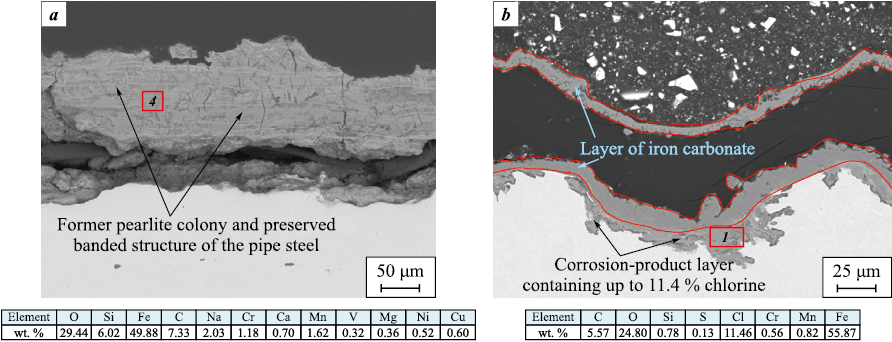

The composition and morphology of the corrosion products correspond to the governing corrosion processes. In CO2 corrosion, the formation of FeCO3 is observed; the carbonate inherits the steel microstructure because the reaction Fe3C + CO2 does not proceed, whereas α-Fe (ferrite) reacts with CO2 to form iron carbonate (Fig. 19, a). Blister formation always precedes the growth of the corrosion-product layer, because this layer does not experience mechanical loading and cannot expand freely in the confined space. A corrosion-product layer enriched in chlorine is localized at the metal/corrosion-product interface (Fig. 19, b), which is characteristic of corrosion processes occurring in oilfield tubing. The identical composition and morphology of the corrosion products indicate the absence of selective diffusion or differences in the diffusion rates of individual components through the coating.

Fig. 19. Structures of corrosion products beneath the coating: |

The height of coating blisters may reach ten times the coating thickness, which indicates minimal destructive changes and preservation of elasticity. In the authors’ experience, failures preceded by significant plastic deformation have not been observed even after long service periods (over 10 years); therefore, adhesion loss and blister formation always proceed faster than aging processes accompanied by a reduction in ductility.

Fig. 20. Structure of a single-layer internal coating of production tubing, Ø73×5.5 mm, |

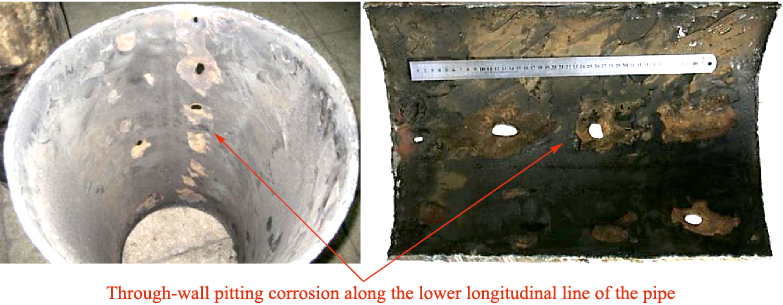

The fourth degradation stage is associated with the rapid development of through-thickness pits. If the coating has not been exposed to elevated temperatures, then by the time this stage is reached substantial destructive changes have often occurred, causing the coating to become brittle and fail easily (Fig. 20). In the presence of coating defects, corrosion damage is intensified for two reasons:

– formation of a galvanic couple in which the blister center acts as the anode, followed by accelerated corrosion after pit initiation and the formation of an additional cathode–anode pair;

– all corrosive activity is concentrated in a single local area; the medium contains no Fe2+ ions (typically released during corrosion of uncoated pipe), which otherwise act as inhibitors for corrosion processes. In such cases, the characteristic failure mode is through-wall pitting corrosion, whereas the coating remains intact on remote sections of the pipe (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. Consequences of operating a pipeline with a degraded internal coating |

Conclusions

1. A comprehensive review of the degradation mechanisms of polymer coatings on metallic substrates has been conducted, including water diffusion and absorption within the polymer matrix, disruption of molecular interactions in the polymer network, adhesion loss and interfacial delamination, interfacial corrosion, cathodic delamination, blister formation, and erosion-driven damage.

2. It has been shown that the degradation of internal anticorrosion coatings in oil pipelines can be divided into four stages. At the first stage, water uptake and diffusion of transported species occur throughout the coating thickness. This is the shortest stage and can be described using Fick’s diffusion equation. During the second stage, interfacial adhesion is degraded; this is the longest and the life-limiting stage in coating performance. The third stage involves blister formation and the development of corrosion products at the metal–coating interface. At the final stage, the blister ruptures, followed by the onset of aggressive through-wall pitting corrosion.

3. Based on the analysis of the composition and morphology of corrosion products beneath the coating and their comparison with corrosion products formed on similar pipe steels operated under comparable conditions, it has been established that diffusion selectivity is absent. No substantial limitation on the transport of any specific corrosion-active species was observed.

4. It has been demonstrated that visual inspection alone cannot reliably identify the root cause of coating failure, because overheating by only a few degrees above the wet-state glass-transition temperature of the polymer may significantly contribute to degradation. Although such overheating does not intensify thermo-oxidative processes and is not detectable by DSC or FTIR analysis, its presence reduces the coating service life by approximately an order of magnitude.

References

1. Zhao L., Ren J., Dunne T. R., Cheng P. Surface engineering solutions for corrosion protection in CCUS tubular applications. In: Surface engineering – foundational concepts, techniques and applications. Wang J., Li C. (eds.). China: InTech, 2025. P. 1–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1007112

2. Zargarnezhad H., Asselin E., Wong D., Lam C.C. A critical review of the time-dependent performance of polymeric pipeline coatings: Focus on hydration of epoxy-based coatings. Polymers. 2021;13(9):1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13091517

3. Odette N.F., Soboyejo W. Failure mechanisms in pipeline epoxy coatings. Advanced Materials Research. 2016; 1132:366–384. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1132.366

4. Zumelzu E., Ortega C., Rull F., Cabezas C. Degradation mechanism of metal–polymer composites undergoing electrolyte induced delamination. Surface Engineering. 2011;27(7):485–490. https://doi.org/10.1179/026708410X12687356948

5. Shreepathi S. Physicochemical parameters influencing the testing of cathodic delamination resistance of high build pigmented epoxy coating. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2016;90:438–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2015.11.007

6. Nazarov A.P., Thierry D. Mechanism of the corrosion exfoliation of a polymer coating from a carbon steel. Protection of Metals and Physical Chemistry of Surfaces. 2009;45:735–745. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2070205109060173

7. Leidheiser Jr H., Wang W., Igetoft L. The mechanism for the cathodic delamination of organic coatings from a metal surface. Progress in Organic Coatings. 1983:11(1):19–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-0655(83)80002-8

8. Watts J.F. Mechanistic aspects of the cathodic delamination of organic coatings. The Journal of Adhesion. 1989;31(1):73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00218468908048215

9. Kendig M., Addison R., Jeanjaquet S. The mechanism of cathodic disbonding of hydroxy‐terminated polybutadiene on steel from acoustic microscopy and surface energy analysis. Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 1990;137(9):2690. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2087011

10. Pud A.A., Shapoval G.S. Electrochemistry as the way to transform polymers. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A. 1995;32(sup1):629–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/10601329508018952

11. Kendig M., Mills D.J. An historical perspective on the corrosion protection by paints. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2017;102:53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2016.04.044

12. Sander J., Manea V., Kirmaier L., Shchukin D., Skorb E. Anticorrosive coatings: Fundamental and new concepts. Hannover, Germany: Vincentz Network, 2014. 216 p. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783748602194

13. Haji-Ghassemi M., Gowers K.R., Cottis R. Hydrogen permeation measurement on lacquer coated mild steel under cathodic polarisation in sodium chloride solution. Surface Coatings International. 1992;75:277–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21941-7

14. Cupertino-Malheiros L., Duportal,M., Hageman T., Zafra A., Martínez-Pañeda E. Hydrogen uptake kinetics of cathodic polarized metals in aqueous electrolytes. Corrosion Science. 2024;231:111959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2024.111959

15. Petrunin M.A., Maksaeva L.B., Gladkikh N.A., Yurasova T.A., Maleeva M.A., Ignatenko V. E. Cathodic delamination of polymer coatings from metals. Mechanism and prevention methods. A review. International Journal of Corrosion and Scale Inhibition. 2024;10(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.17675/2305-6894-2021-10-1-1

16. Nazarov A., Thierry D. Application of Scanning Kelvin probe in the study of protective paints. Frontiers in Materials. 2019;6:192. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2019.00192

17. Funke W. Blistering of paint films and filiform corrosion. Progress in Organic coatings. 1981;9(1):29–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-0655(81)80014-3

18. Sabet-Bokati K., Plucknett K. Water-induced failure in polymer coatings: Mechanisms, impacts and mitigation strategies – A comprehensive review. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2024;230:111058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2024.111058

19. Cristoforetti A., Izquierdo J., Souto R.M., Deflorian F., Fedel M., Rossi, S. In-situ measurement of electrochemical activity related to filiform corrosion in organic coated steel by scanning vibrating electrode technique and scanning micropotentiometry. Corrosion Science. 2024; 227:111669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111669

20. Liu Y., Wang J., Liu L., Li Y., Wang F. Study of the failure mechanism of an epoxy coating system under high hydrostatic pressure. Corrosion Science. 2013;74:59–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2013.04.012

21. Knudsen O.O., Bjørgum A., Kvernbråten, A.K. Internal coating of multiphase pipelines-requirements for the coating. In: Corrosion 2010 (March 14–18, 2010). San Antonio, Texas: NACE CORROSION, 2010. 10004 p.

22. Zargarnezhad H., Wong D., Lam C.C., Asselin E. Long-term performance of epoxy-based coatings: Hydrothermal exposure. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2024; 196:108697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2024.108697

23. Rajagopalan N., Weinell C.E., Dam-Johansen K., Kiil S. Degradation mechanisms of amine-cured epoxy novolac and bisphenol F resins under conditions of high pressures and high temperatures. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2021;156:106268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106268

24. Rajagopalan N., Weinell C.E., Dam-Johansen K., Kiil S. Influence of CO2 at HPHT conditions on the properties and failures of an amine-cured epoxy novolac coating. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2021;60(41):14768–14778. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.iecr.1c02713

25. Rajagopalan N., Olsen M., Larsen T.S., Fjælberg T.J., Weinell C.E., Kiil S. Protective mechanisms of siloxane-modified epoxy novolac coatings at high-pressure, high-temperature conditions. ACS omega. 2024;9(28):30675–30684. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c02986

26. Yang C., Xing X., Li Z., Zhang S. A comprehensive review on water diffusion in polymers focusing on the polymer–metal interface combination. Polymers. 2020;12(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12010138

27. Bratasyuk N.A., Latyshev A.V., Zuev V.V. Water in epoxy coatings: Basic principles of interaction with polymer matrix and the influence on coating life cycle. Coatings. 2023;14(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings14010054

28. Nogueira P., Ramirez C., Torres A., Abad M.J., Cano J., Lopez J., López‐Bueno I., Barral L. Effect of water sorption on the structure and mechanical properties of an epoxy resin system. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2001;80(1):71–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4628(20010404)80:1<71::AID-APP1077>3.0.CO;2-H

29. Chiang M.Y., Fernandez‐Garcia M. Relation of swelling and Tg depression to the apparent free volume of a particle – filled, epoxy – based adhesive. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2023;87(9):1436–1444. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1002/app.11576

30. Luo S., Leisen J., Wong C.P. Study on mobility of water and polymer chain in epoxy and its influence on adhesion. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2002;85(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.10473

31. Mallarino S., Renaud A., Trinh D., Touzain S. The role of internal stresses, temperature, and water on the swelling of pigmented epoxy systems during hygrothermal aging. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2022; 139(46):53162. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.53162

32. Alessi S., Toscano A., Pitarresi G., Dispenza C., Spadaro G. Water diffusion and swelling stresses in ionizing radiation cured epoxy matrices. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2017;144:137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.08.009

33. Croll S.G. Stress and embrittlement in organic coatings during general weathering exposure: A review. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2022;172:107085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2022.107085

34. Abdelkader A.F., White J.R. Curing characteristics and internal stresses in epoxy coatings: Effect of crosslinking agent. Journal of Materials Science. 2005;40:1843–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-005-1203-9

35. Krauklis A.E., Gagani A.I., Echtermeyer A.T. Long-term hydrolytic degradation of the sizing-rich composite interphase. Coatings. 2019;9(4):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings9040263

36. Capiel G., Uicich J., Fasce D., Montemartini P.E. Diffusion and hydrolysis effects during water aging on an epoxy-anhydride system. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2018;153:165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2018.04.030

37. Göpferich A. Mechanisms of polymer degradation and erosion. Biomaterials. 1996;17(2): 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-9612(96)85755-3

38. Grujicic M., Sellappan V., Omar M.A., Seyr N., Obieglo A., Erdmann M., Holzleitner J. An overview of the polymer-to-metal direct-adhesion hybrid technologies for load-bearing automotive components. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2008;197(1-3):363–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.06.058

39. Schmidt R.G., Bell J.P. Epoxy adhesion to metals. Epoxy Resins and Composites II. Advances in Polymer Science. 2005;72:33–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0017914

40. Posner R., Ozcan O., Grundmeier G. Water and ions at polymer/metal interfaces. Design of Adhesive Joints Under Humid Conditions. Advanced Structured Materials. 2013;25:21–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37614-6_2

41. Fan X., Zhang G.Q., Van Driel W.D., Ernst L.J. Interfacial delamination mechanisms during soldering reflow with moisture preconditioning. IEEE Transactions on Components and Packaging Technologies. 2008;31(2):252–259. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCAPT.2008.921629

42. Chen F., Jin Z., Wang E., Wang L., Jiang Y., Guo P., Gao X., He X. Relationship model between surface strain of concrete and expansion force of reinforcement rust. Scientific Reports. 2021;11:4208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83376-w

43. Saarimaa V., Virtanen M., Laihinen T., Laurila K., Väisänen P. Blistering of color coated steel: Use of broad ion beam milling to examine degradation phenomena and coating defects. Surface and Coatings Technology. 2022;448:128913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2022.128913

44. Sørensen P.A., Kiil S., Dam-Johansen K., Weinell C.E. Influence of substrate topography on cathodic delamination of anticorrosive coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2009;64(2-3):142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.08.027

45. Sørensen P.A., Dam-Johansen K., Weinell C.E., Kiil S. Cathodic delamination of seawater-immersed anticorrosive coatings: Mapping of parameters affecting the rate. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2010;68(4):283–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2010.03.012

46. Jorcin J.B., Aragon E., Merlatti C., Pébère N. Delaminated areas beneath organic coating: A local electrochemical impedance approach. Corrosion Science. 2006;48(7):1779–1790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2005.05.031

47. Yang X.F., Tallman D.E., Bierwagen G.P., Croll S.G., Rohlik S. Blistering and degradation of polyurethane coatings under different accelerated weathering tests. Polymer degradation and stability. 2002;77(1):103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00085-X

48. Kotb Y., Serfass C.M., Cagnard A., Houston K.R., Khan S.A., Hsiao L.C., Velev O.D. Molecular structure effects on the mechanisms of corrosion protection of model epoxy coatings on metals. Materials Chemistry Frontiers. 2023;7(2):274–286. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2QM01045C

49. Prosek T., Nazarov A., Olivier M.G., Vandermiers C., Koberg D., Thierry D. The role of stress and topcoat properties in blistering of coil-coated materials. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2010;68(4):328–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2010.03.003

50. Effendy S., Zhou T., Eichman H., Petr M., Bazant M.Z. Blistering failure of elastic coatings with applications to corrosion resistance. Soft Matter. 2021;17(11): 9480–9498. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1SM00986A

51. Hoseinpoor M., Prošek T., Mallégol J. Mechanism of blistering of deformed coil coated sheets in marine climate. Corrosion Science. 2023;212:110962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2023.110962

52. Bi H., Sykes J. Cathodic disbonding of an unpigmented epoxy coating on mild steel under semi-and full-immersion conditions. Corrosion Science. 2011;53(10):3416–3425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2011.06.021

53. Meng F., Liu L., Liu E., Zheng H., Liu R., Cui Y., Wang F. Synergistic effects of fluid flow and hydrostatic pressure on the degradation of epoxy coating in the simulated deep-sea environment. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2021;159:106449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106449

54. Zhou Q., Wang Y., Bierwagen G.P. Flow-accelerated coating degradation: Influence of the composition of working fluids. In: Corrosion 2012 (March 11–14, 2012). Salt Lake City, UT: NACE INTERNATIONAL; 2012. C2012-01656 p.

55. Wood R.J. Tribo-corrosion of coatings: A review. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2007;40(18):5502. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/40/18/S10

56. Wang D., Sikora E., Shaw B. A study of the effects of filler particles on the degradation mechanisms of powder epoxy novolac coating systems under corrosion and erosion. Progress in Organic Coatings. 2018;121:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2018.04.026

57. Yudin P.E. Functional coatings of submersible oilfield equipment for protection against corrosion, asphalt, resin, paraffin and salt deposits: Review. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings. 2025;19(1):58–74. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-1-58-74

58. Bogatov M.V., Yudin P.E., Maidan D.A. Influence of the water absorption process on the physical and mechanical properties of the free coating film. Neftegazovoe delo. 2025;23(1):77–90. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17122/ngdelo-2025-1-77-90

About the Authors

P. E. YudinRussian Federation

Pavel E. Yudin – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor of the Department of metal science, powder metallurgy, nanomaterials of Samara State Technical University; Director of Science of Samara Scientific and Production Center, LLC

133 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443001, Russia

3B Garazhny Pr., Samara 443022, Russia

A. S. Lozhkomoev

Russian Federation

Aleksandr S. Lozhkomoev – Dr. Sci. (Eng.), Leading Researcher

2/4 Akademicheskiy Prosp., Tomsk 634055, Russia

Review

For citations:

Yudin P.E., Lozhkomoev A.S. Mechanisms of failure in anti-corrosion polymer coatings on metallic surfaces of oilfield pipelines: Review. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(6):65-82. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-6-65-82