Scroll to:

Investigation of the properties of WC–5TiC–10Co cutting inserts produced using a 3D-printed plastic mold

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-5-55-65

Abstract

Cutting inserts made from the WC–5TiC–10Co hard alloy were produced by sintering blanks that were pressed in a plastic mold made from polylactide on a 3D printer using a layer-by-layer deposition method. The effect of pressing pressure and plasticizer (rubber) content in the powder mixture on the density of the blanks was studied. As the pressing pressure increased from 50 to 200 MPa, the density of the blanks rose by only 2–6 %. When the plasticizer concentration in the powder mixture increased from 1 to 6 %, the blank density increased by 28–32 %. It was found that the density values of the cutting insert blanks obtained in a plastic mold differed only slightly from those of standard blanks produced in a steel mold. After sintering in a vacuum furnace at 1450 °C, the density, carbon content, porosity, microstructure, surface roughness, hardness, and fracture toughness of all the sintered cutting inserts, standard samples, and the commercial equivalent were investigated. It was shown that the formation of free carbon as a result of rubber decomposition leads to a decrease in the density of the finished products, and therefore, their hardness. The relative density (98.7 %) of the cutting insert produced in the plastic mold at a pressing pressure of 50 MPa from powder containing 1 % rubber exceeded the density of the commercial cutting insert (98.5 %). The obtained cutting insert demonstrated high hardness (1400 HV) and fracture toughness (13.5 MPa·m1/2). The cutting insert made from the WC–5TiC–10Co alloy is not inferior to the commercial T5K10 hard alloy insert in terms of flank wear rate during turning of a steel workpiece.

For citations:

Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A., Burkov A.A., Chernyakov E.V. Investigation of the properties of WC–5TiC–10Co cutting inserts produced using a 3D-printed plastic mold. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2024;18(5):55-65. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-5-55-65

Introduction

Hard alloys based on WC and TiC are widely used in metalworking [1]. Industrial production of hard alloy products is based on sintering blanks obtained by cold pressing in steel or hard alloy molds. These molds ensure the necessary density and high precision, possess high productivity, and have a long service life, but are limited in terms of product shape and require significant costs for their manufacturing. In recent years, additive technologies have been employed to produce complex-shaped hard alloy products from structural materials [2–4]. However, these methods face certain challenges. For example, producing high-density hard alloy products using selective laser sintering is complicated by changes in chemical composition [4–15], while blanks for sintering obtained by binder jetting (BJ) [4; 16–23], fused filament fabrication (FFF) [24], and gel-based 3D printing (3DGP) [25; 26] have reduced density due to the lack of pressure.

An alternative method involves using plastic molds manufactured on a 3D printer for slip casting of hard alloy and ceramic blanks, which are later sintered using conventional methods [27; 28]. When using these methods, the volumetric fraction of the plasticizer must be significantly increased (over 50 vol. %). Removing the plasticizer from the blanks creates pores, reducing the density of the products made using these methods. Studies have shown that WC–15Co hard alloy blanks can be produced by pressing at pressures up to 120 MPa in plastic molds made by layer-by-layer deposition [29]. The resulting alloy samples match the density and characteristics of those obtained by pressing in conventional steel molds. Expanding the applicability of this method requires broadening the range of materials used and increasing pressing conditions.

The goal of this study was to investigate the effect of plasticizer concentration and pressing pressure (up to 200 MPa) in plastic molds on the density, microstructure, hardness, and fracture toughness of cutting inserts made from the WC–5TiC–10Co hard alloy. The wear resistance of the obtained samples was also compared with a commercial equivalent.

Research methodology

To assess the effect of plasticizer concentration and pressing pressure on the properties of the experimental samples, 200 g of WC–5TiC–10Co powder was prepared by mixing powders from the Kirovgrad Hard Alloy Plant: WC (73.3 %, WC3), (Ti,W)C (16.7 %, TWC3), and Co (10 %, PK1U)) in a PM-400 planetary mill (Retsch, Germany) for 120 min at 350 rpm. The ball-to-powder mass ratio was 3:1. After mixing, the powder was divided into four equal parts, each of which was supplemented with 1, 2, 4, and 6 wt. % rubber as a solution. The resulting mixtures were pressed after drying and granulation.

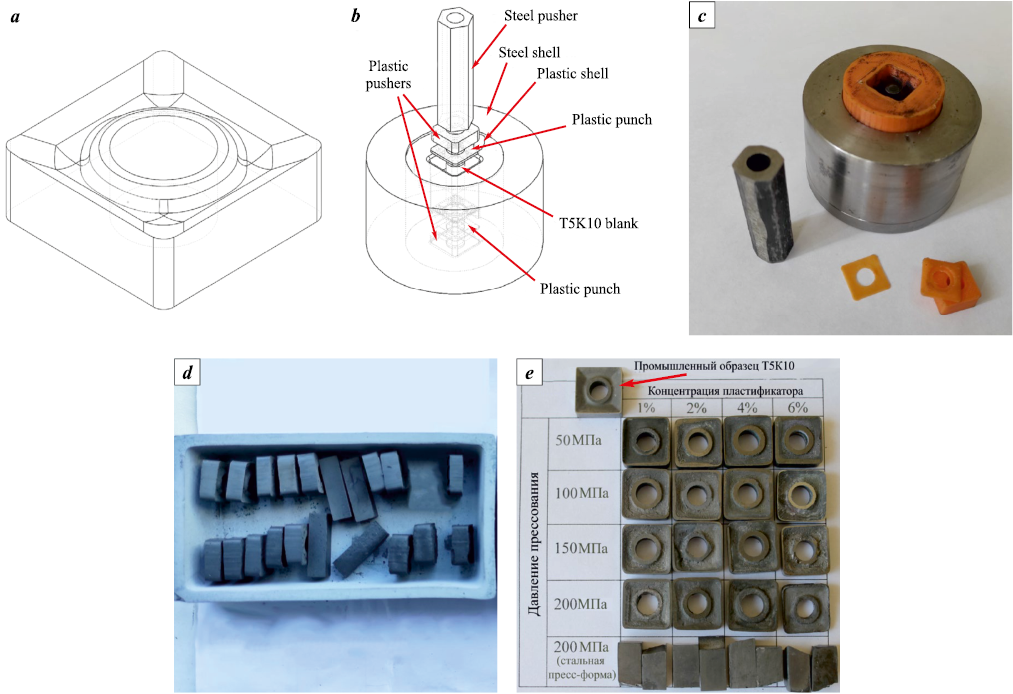

The plastic mold for pressing the SNUM-120408 cutting insert blanks (Fig. 1, c) was made of polylactide (PLA, produced by Bestfilament, Tomsk) using layer-by-layer deposition technology on a Flash Forge Dreamer 3D printer (China). The filling was 100 %, with a first layer thickness of 0.27 mm and subsequent layers of 0.1 mm. The printing temperature was 200 °C. The compressive strength, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio of the plastic, according to test results, were 70 MPa, 1.54 GPa, and 0.38, respectively [29; 30]. A steel shell, steel rod, and steel pusher were used to ensure high pressing pressures (up to 200 MPa) in the plastic mold (Fig. 1, b, c).

Fig. 1. 3D model of the cutter (a), mold diagram (b), mold (c), blanks after pressing (d), |

From each batch of powder, four samples weighing 8 g each were pressed in plastic molds at pressures of 50, 100, 150, and 200 MPa, and one rectangular blank measuring 24×8×8 mm was pressed in a steel mold at 200 MPa for comparison. A total of 20 different samples were obtained (Fig. 1, e). After pressing, the density of the obtained blanks was measured. The blanks were sintered after plasticizer removal (Fig. 1, d) at a maximum temperature of 1450 °C. After sintering, the samples were ground and polished for microstructure analysis. Hardness, fracture toughness, and strength (only for rectangular samples) were measured, and wear resistance tests were conducted during the turning of steel 45 using the cutting insert produced at a pressing pressure of 50 MPa from a powder mixture containing 1 % rubber, compared with the commercial SNUM-120408 insert made from the T5K10 alloy by KZTS.

Pressing and testing of the punches and sintered samples were conducted on an IP-250M test press (ZIPO LLC, Armavir) at a loading rate of 0.5 kN/s. The pressing force required to achieve pressures of 50, 100, 150, and 200 MPa was calculated based on the punch area (191 mm2) and the friction force against the walls of the matrix (11 % of the force). The density of the powder compacts and sintered samples was determined by hydrostatic weighing on Vibra scales (Shinko, Japan). The relative densities of the powder compacts and sintered samples were calculated based on the known densities of the WC–5TiC–10Co alloy (12.95 g/cm3) and rubber (0.9 g/cm3). Plasticizer removal and sintering were performed in a Carbolite STF vacuum furnace (Carbolite Gero, UK). Strength testing of rectangular samples was carried out according to standard methodology (ISO 3327:2009). Carbon content in the powders was measured on an EMIA 320V2 analyzer (Horiba Ltd., Japan) after the removal of the plasticizer by heating along with other samples. The microstructure of the sintered hard alloy products was examined using optical (Altami, St. Petersburg) and scanning electron microscopes (Tescan Orsay Holding, Czech Republic). The average grain diameter was calculated using standard methodology (ASTM E112-13). The Vickers hardness of all samples was determined using an HVS-50 hardness tester (Time Group Inc., China) (with an accuracy of 2 %) at a load of P = 294 N. Fracture toughness (K1c ) was calculated based on the total crack length (Σl) from the hardness tester indenter using the Palmqvist method (ISO 28079) at a load of P = 294 N according to the Shetty equation:

| \[{K_{1c}} = 0.0028\sqrt {HV\frac{P}{{\Sigma l}}} .\] | (1) |

The performance characteristics of the obtained cutting insert (1 % rubber, pressure of 50 MPa) and the commercial insert were determined during rough turning (cutting speed of 100 ± 10 m/min, depth of 1.5 mm, feed of 0.2 mm/rev, duration of 3.5 min, length of 330 m) and finishing (cutting speed of 125 ± 15 m/min, depth of 0.2 mm, feed of 0.05 mm/rev, duration of 10.5 min, length of 1320 m) of a cylindrical workpiece with a diameter of 50 to 60 mm made of steel 45 on a 16K20 lathe (Krasny Proletary Plant, Moscow). The profiles of the rear surfaces of the cutting inserts and steel workpieces were examined using a Tr-200 profilometer (Time Group Inc., China).

Results and discussion

The observed ability of polylactide punches to withstand a pressing pressure of 70 MPa, exceeding the yield strength of this material, is explained by the fact that, according to the von Mises criterion, under such a load, the resulting equivalent stress decreases due to the presence of the second and third principal stresses within the steel shell (Fig. 1, b, c). Additionally, friction between the punch, the matrix walls, and the pusher leads to a reduction (by 11 ± 5 %) in the pressure exerted on the blank. The dependence of the relative density of the blanks (ρ) on the pressure (P) (Fig. 2, a) is well described by the known relationship [31]:

| ρ = A + B lnP. | (2) |

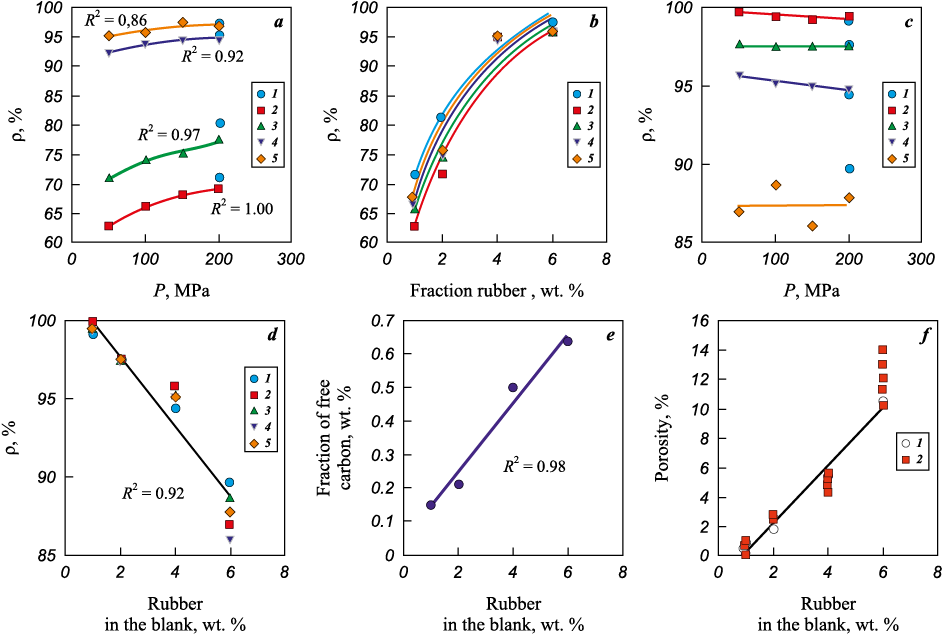

Fig. 2. Dependence of the density of compacts (а, b) and sintered samples (c, d) |

The parameter B characterizes the rate of density increase with increasing pressure. Thus, as the pressing pressure increases from 50 to 200 MPa, the density of the blanks increases by 2–6 % for different plasticizer concentrations (Fig. 2, a), in full agreement with the relationship (2). The relatively small density increase with increasing pressure should prevent uneven density distribution during blank pressing. The coefficient A in equation (2) shows the density achieved at the initial stage of pressing at relatively low pressure, which depends on the plasticizer content and other parameters of the mixture. The relative density of the blanks pressed at 50 MPa increases from 62 to 95 % as the plasticizer concentration increases from 1 to 6 % (Fig. 2, b).

An increase in the plasticizer fraction from 1 to 6 % leads to a 28–32 % increase in blank density at various pressing pressures (Fig. 2, b), which is significantly greater than the density increase caused by increasing the pressing pressure (Fig. 2, a). The density of all the obtained blanks exceeded the density of blanks manufactured using other 3D printing methods by 20–45 % [19; 21–23; 28; 32]. This is primarily due to the fact that in 3D printing, direct compaction occurs only under the influence of gravity and surface tension forces. Fig. 2, a and b show that the density of the blanks obtained in a steel mold at 200 MPa is no different from the density of the blanks obtained in a plastic mold at the same pressure and plasticizer content.

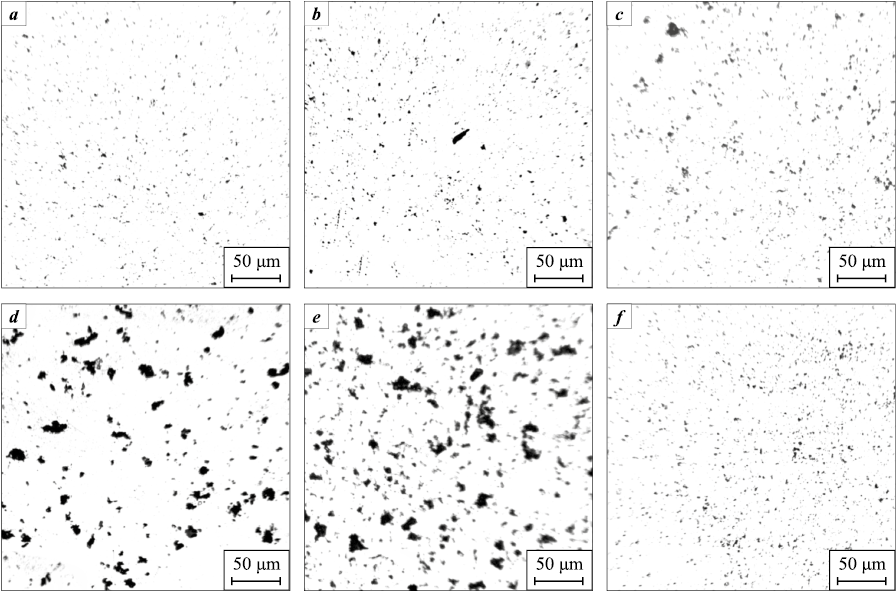

For the sintered samples, it was found that changes in pressing pressure have almost no effect on their density (Fig. 2, c). Increasing the rubber concentration from 1 to 6 % leads to a decrease in the density of the products from 99.3–99.8 to 86.0–88.6 % (Fig. 2, d), which is due to the increase in free carbon concentration formed during rubber decomposition. Analysis showed that the amount of free carbon in the sintered samples increases linearly from 0.15 to 0.64 % as the rubber concentration in the blanks rises from 1 to 6 % (Fig. 2, e), corresponding to the formation of approximately 0.1 % free carbon per 1 % rubber. The increase in the porosity of the samples correlates well with the increase in free carbon content (Fig. 2, f), meaning the pores detected in the microstructure are actually inclusions of free carbon. The porosity values obtained by analyzing their share in the microstructure surface area (Fig. 3, a–e) also fit this pattern (Fig. 2, f). It should be noted that the relative density (99.8 %) of the sample pressed at 50 MPa from powder containing 1 % rubber is equal to the density of the commercial cutting insert (99.8 %).

Fig. 3. Microstructures of samples sintered after pressing at pressing at 50 MPa (а, c–e) |

The sintered samples also do not fall behind in relative density compared to the best WC–Co alloy samples with cobalt content up to 15 %, obtained by direct SLM and SLS methods (densities, %: 96 [5], 96.1 [11], 97.3 [16], 92.4 [17], 98 [33], 97.4 [34]). There is a slight lag in relative density compared to the samples produced by sintering blanks obtained by BJ (100 % [23], 100 % [24]) and FFF methods (>99 % [35]). Considering that the density of the blanks obtained by BJ and FFF methods (20–45 %) is significantly lower than the density of the blanks obtained in this study (65–95 %) (Fig. 2, a, b), it can be assumed that the slight lag in density of the obtained sintered samples (1 %) is due to the lower sinterability of the WC–TiC–Co alloy compared to WC–Co alloys and the less advanced sintering method (LPS).

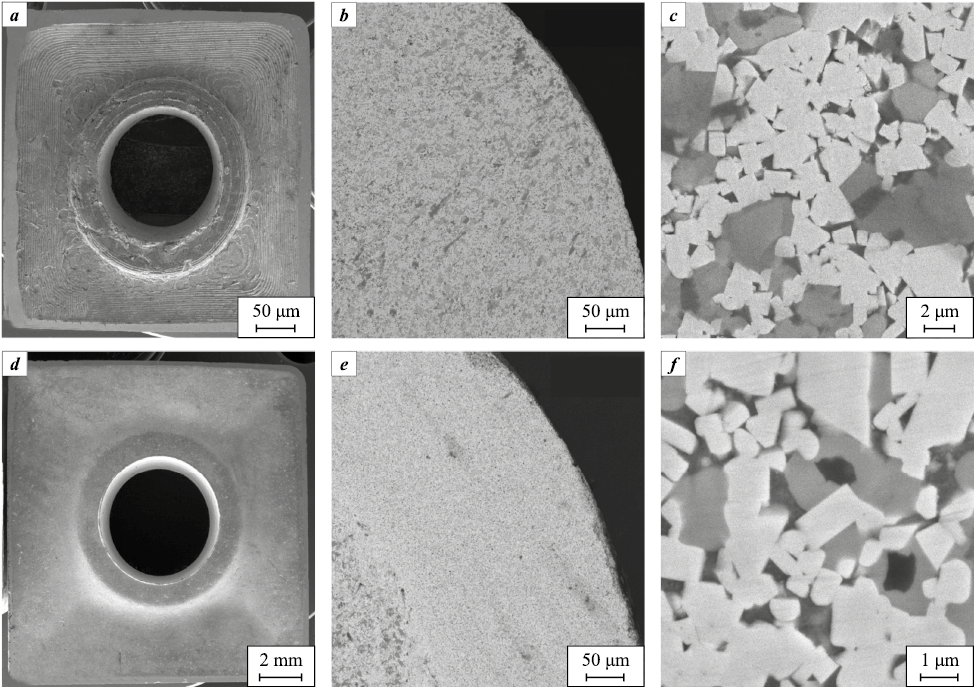

The projections of the obtained and commercial cutting inserts are similar to each other (Fig. 4, a, d). The surface of the insert sintered after pressing in a plastic mold is distinguished by the characteristic traces of layers obtained during 3D printing. In addition, the microstructure of the obtained sample shows defects formed during the separation of the plastic punch from the blank. The side surface does not have such defects. There are no large defects on the polished section that would differentiate the obtained sample (Fig. 4, b) from the commercial counterpart (Fig. 4, e). Microstructure analysis showed that the obtained sample (Fig. 4, c) has a larger carbide grain size (average WC grain diameter davg = 1.26 µm) compared to the commercial counterpart (Fig. 4, f) (davg = 0.88 µm). It can be expected that the other samples also have a larger average grain diameter.

Fig. 4. Macrostructures (а, d) and microstructures (b, c, e, f) of the WC–5TiC–10Co hard alloy |

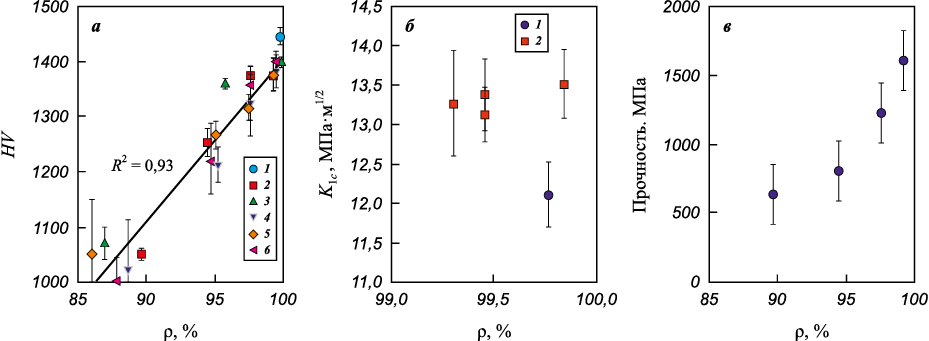

The hardness of the samples pressed in the plastic mold increases from 1010 to 1400 HV as their density rises from 85.0 to 98.7 % (Fig. 5, a). Measurements showed that the fracture toughness of these samples is largely independent of their density (Fig. 5, b). The presented dependencies (Fig. 5, a, b) show that the commercial cutting insert has higher hardness (1450 ± 10 HV) and lower fracture toughness (12.1 ± 0.4 MPa·m\(^{1/2}\)). According to the analysis of sintered samples obtained by pressing in a steel mold, their strength increases with rising density (Fig. 5, c).

Fig. 5. Dependence of hardness (a), fracture toughness (b), and strength (c) |

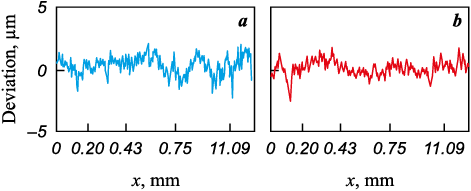

Profile measurements of the cutting inserts (Fig. 6) showed that the roughness of the experimental tool was predictably higher than that of the commercial cutting insert (see Table), due to surface micro-irregularities formed during pressing. These irregularities resulted from the adhesion of plastic to the blank and the replication of imperfections in the plastic mold’s surface, which were introduced during 3D printing.

Fig. 6. Profile of the side surface of the experimental (b)

Results of testing cutting inserts when turning steel 45

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

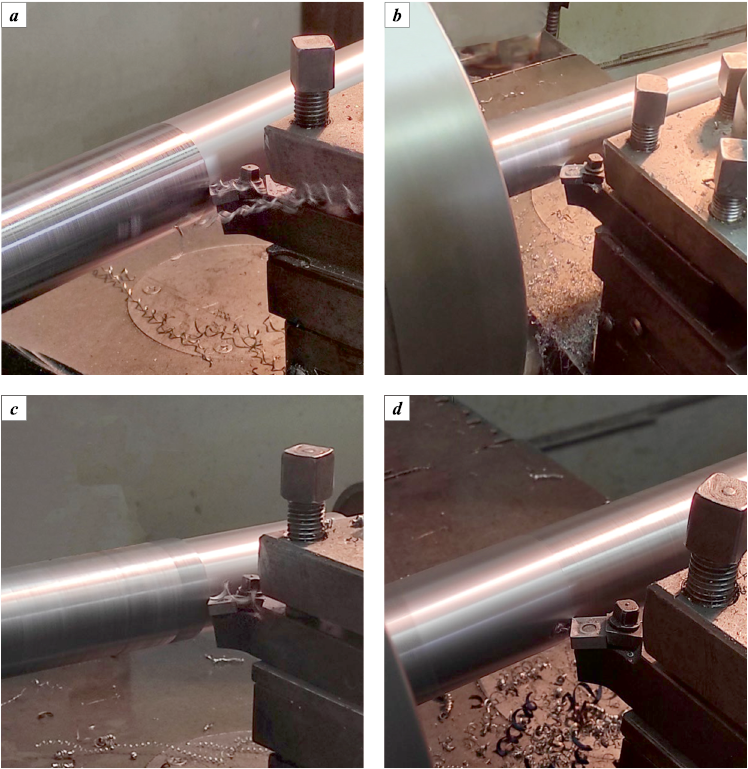

Hardness and roughness are the primary factors influencing the performance of both the experimental (Fig. 7, a, b) and commercial (Fig. 7, c, d) cutting inserts, made from the same material, during rough (Fig. 7, a, c) and finishing (Fig. 7, b, d) turning. The increased roughness and lower hardness of the experimental insert resulted in 5–7 % higher surface roughness on the workpieces after both rough and finishing turning compared to the commercial insert (see Table).

Fig. 7. Rough (а, c) and finishing (b, d) turning using the experimental (а, b) |

Adhesive wear of the WC–5TiC–10Co alloy cutting inserts during carbon steel turning, where continuous chips are formed (Fig. 7, a, c), predominates over other types of wear. In this process, the composition of the cutting inserts plays the most significant role, and since the composition is the same in both cases, differences in hardness have less impact. The wear on the rear edge of the experimental cutting insert during both rough and finishing turning was 5–6 % higher than that of the commercial counterpart. In this case, the main cause was the difference in hardness.

Conclusions

The experimental results confirmed that using a polylactide mold produced by additive manufacturing, complemented by a steel shell and pusher, enables the pressing of hard alloy blanks at pressures up to 200 MPa. The density of the cutting insert blanks pressed in these molds from WC–5TiC–10Co is only slightly different from the density of blanks produced in steel molds at the same pressure. As pressing pressure increases, the density of the blanks grows only by 2–6 %, while increasing the plasticizer concentration in the initial powder mixture by 1 to 6 % results in a more significant density increase of 28–32 %.

The pressing pressure has little impact on the density of sintered cutting inserts. As the plasticizer concentration increases (from 1 to 6 %), the free carbon concentration rises (from 0.15 to 0.64 %), which leads to a decrease in the relative density, hardness, and strength of the samples. Cutting inserts made from WC–5TiC–10Co powder with 1 % plasticizer have similar density and porosity to commercial T5K10 inserts. However, they exhibit lower hardness (1400 ± 10 HV) and higher fracture toughness (135 ± 0.4 MPa·m\(^{1/2}\) ) compared to commercial samples (1447 ± 15 HV and 121 ± 0.4 MPa·m\(^{1/2}\)) of the same alloy, primarily due to the larger average WC grain size. The wear rate of the experimental cutting insert is 5–7 % higher than that of the commercial tool, due to its lower hardness and higher surface roughness.

References

1. Anisimenko G.E., Lopatin Yu.M. New hard alloys for indexable multifaceted inserts. Obrabotka metallov (Tekhnologii, oborudovanie, instrumenty). 2008;4(41):25–33. (In Russ.).

2. Aramian A., Razavi N., Sadeghian Z., Berto F. A review of additive manufacturing of cermets. Additive Manufacturing. 2020;33:101130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101130

3. Yang Y., Zhang C., Wang D., Nie L., Wellmann D., Tian Y. Additive manufacturing of WC–Co hardmetals: A review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2020;108:1653–1673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-05389-5

4. Chen C., Huang B., Liu Z., Li Y., Zou D., Liu T., Chang Y., Chen L. Additive manufacturing of WC–Co cemented carbides: Process, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Additive Manufacturing. 2023:10341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103410

5. Chen J., Huang M., Fang Z.Z., Koopman M., Liu W., Deng X., Zhao Z., Chen S., Wu S., Liu J., Qi W., Wang Z. Microstructure analysis of high density WC–Co composite prepared by one step selective laser melting. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2019;84:104980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.104980

6. Li C.W., Chang K.C., Yeh A.C. On the microstructure and properties of an advanced cemented carbide system processed by selective laser melting. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2019;782:440–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.12.187

7. Gu D., Meiners W. Microstructure characteristics and formation mechanisms of in situ WC cemented carbide based hardmetals prepared by Selective Laser Melting. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2010;527(29–30):7585–7592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2010.08.075

8. Domashenkov A., Borbély A., Smurov I. Structural modifications of WC/Co nanophased and conventional powders processed by selective laser melting. Materials and Manufacturing Processes. 2017;32(1):93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2016.1176195

9. Fortunato A., Valli G., Liverani E., Ascari A.. Additive manufacturing of WC–Co cutting tools for gear production. Lasers in Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2019;6:247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40516-019-00092-0

10. Khmyrov R.S., Shevchukov A.P., Gusarov A.V., Tarasova T.V. Phase composition and microstructure of WC–Co alloys obtained by selective laser melting. Mechanics & Industry. 2017;18(7):714. https://doi.org/10.1051/meca/2017059

11. Ku N., Pittari III J.J., Kilczewski S., Kudzal A. Additive manufacturing of cemented tungsten carbide with a cobalt-free alloy binder by selective laser melting for high-hardness applications. Journal of the Minerals, Metals and Materials Socity (JOM). 2019;71(4):1535–1542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-019-03366-2

12. Zhang L., Hu C., Yang Y., Misra R.D.K., Kondoh K., Lu Y. Laser powder bed fusion of cemented carbides by developing a new type of Co coated WC composite powder. Additive Manufacturing. 2022;55:102820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102820

13. Suzuki A., Shiba Y., Ibe H., Takata N., Kobashi M. Machine-learning assisted optimization of process parameters for controlling the microstructure in a laser powder bed fused WC/Co cemented carbide. Additive Manufacturing. 2022;59:103089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.103089

14. Maurya H.S., Kosiba K., Juhani K., Sergejev F., Prashanth K.G. Effect of powder bed preheating on the crack formation and microstructure in ceramic matrix composites fabricated by laser powder-bed fusion process. Additive Manufacturing. 2022;58:103013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.103013

15. Padmakumar M. Additive manufacturing of tungsten carbide hardmetal parts by selective laser melting (SLM), selective laser sintering (SLS) and binder jet 3D printing (BJ3DP) techniques. Lasers in Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2020;7(3):338–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40516-020-00124-0

16. Mostafaei A., De Vecchis P.R., Kimes K.A., Elhassid D., Chmielus M. Effect of binder saturation and drying time on microstructure and resulting properties of sinter-HIP binder-jet 3D-printed WC–Co composites. Additive Manufacturing. 2021;46:102128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.102128

17. Mariani M., Goncharov I., Mariani D., De Gaudenzi G.P., Popovich A., Lecis N., Vedani M. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of WC–Co consolidated by binder jetting additive manufacturing. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2021;100:105639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2021.105639

18. Cramer C.L., Wieber N.R., Aguirre T.G., Lowden R.A., Elliott A.M. Shape retention and infiltration height in complex WC–Co parts made via binder jet of WC with subsequent Co melt infiltration. Additive Manufacturing. 2019;29:100828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.100828

19. Cramer C.L., Nandwana P., Lowden R.A., Elliott A.M. Infiltration studies of additive manufacture of WC with Co using binder jetting and pressureless melt method. Additive Manufacturing. 2019;28:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2019.04.009

20. Enneti R.K., Prough K.C., Wolfe T.A., Klein A., Studley N., Trasorras J.L. Sintering of WC–12%Co processed by binder jet 3D printing (BJ3DP) technology. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2018;71:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2017.10.023

21. Kim H., Kim J.I., Do Kim Y., Jeong H., Ryu S.S. Material extrusion-based three-dimensional printing of WC–Co alloy with a paste prepared by powder coating. Additive Manufacturing. 2022;52:102679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102679

22. Tang J.Y., Lu L.M., Li Z., Za X., Wu Y.C. Shape retention of cemented carbide prepared by Co melt infiltration into un-sintered WC green parts made via BJ3DP. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials, 2022;107:105904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2022.105904

23. Wolfe T., Shah R., Prough K., Trasorras J.L. Coarse cemented carbide produced via binder jetting 3D printing. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2023;110:106016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2022.106016

24. Lengauer W., Duretek I., Fürst M., Schwarz V., Gonzalez-Gutierrez J., Schuschnigg S., Kukla C., Kitzmantel M., Neubauer E., Lieberwirth C., Morrison V. Fabrication and properties of extrusion-based 3D-printed hardmetal and cermet components. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2019:82:141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.04.011

25. Carreño-Morelli E., Alveen P., Moseley S., Rodriguez-Arbaizar M., Cardoso K. Three-dimensional printing of hard materials. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2020;87:105110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.105110

26. Zhang X., Guo Z., Chen C., Yang W. Additive manufacturing of WC–20Co components by 3D gel-printing. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2018;70:215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2017.10.005

27. Kim H., Kim J.I., Ryu S.S., Jeong H. Cast WC–Co alloy-based tool manufacturing using a polymeric mold prepared via digital light processing 3D printing. Materials Letters. 2022;306:130979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2021.130979

28. Liu K., Zhou C., Chen F., Sun H., Zhang K. Fabrication of complicated ceramic parts by gelcasting based on additive manufactured acetone-soluble plastic mold. Ceramics International. 2020;46(16):25220–25229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.06.313

29. Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A., Burkov A.A., Kolzun D.A., Shichalin O.O. 3D printed plastic molds utilization for WC–15Co cemented carbide cold pressing. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2023;106312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2023.106312

30. Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A., Burkov A.A., Kol’zun D.A. Dependence of the density, hardness, strength and sizes of WC–15Co hard alloy samples on the plasticizer content in samples got using a 3D printed mold. Perspektivnye materialy. 2024;(3):33–44. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.30791/1028-978X-2024-3-33-44

31. Niesz D.E. A review of ceramic powder compaction. KONA Powder and Particle Journal. 1996;14:44–51. https://doi.org/10.14356/kona.1996009

32. Xu Z.K., Meenashisundaram G.K., Ng F.L. High-density WC–45Cr–18Ni cemented hard metal fabricated with binder jetting additive manufacturing. Virtual and Physical Prototyping. 2022;17(1):92–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452759.2021.1997006

33. Konyashin I., Hinners H., Ries B., Kirchner A., Kloeden B., Kieback B., Nilen R.W.N., Sidorenko D. Additive manufacturing of WC–13%Co by selective electron beam melting: Achievements and challenges. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2019;84:105028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.105028

34. Fries S., Vogelpoth A., Kaletsch A., Broeckmann C. Influence of post heat treatment on microstructure and fracture strength of cemented carbides manufactured using laser-based additive manufacturing. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2023;111:106085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2022.106085

35. Zhao Z., Liu R., Chen J., Xiong X. Additive manufacturing of cemented carbide using analogous powder injection molding feedstock. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2023;111:106095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2022.106095

About the Authors

M. I. DvornikRussian Federation

Maksim I. Dvornik – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Senior Researcher, Head of the Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

E. A. Mikhailenko

Russian Federation

Elena A. Mikhailenko – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher, Laboratory of Powder Metallurg

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

A. A. Burkov

Russian Federation

Aleksandr A. Burkov – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher, Head of the Laboratory “Physical and Chemical Bases of Materials”

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

E. V. Chernyakov

Russian Federation

Evgeny V. Chernyakov – Laboratory Assistant, Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

Review

For citations:

Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A., Burkov A.A., Chernyakov E.V. Investigation of the properties of WC–5TiC–10Co cutting inserts produced using a 3D-printed plastic mold. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2024;18(5):55-65. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-5-55-65