Scroll to:

Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC composition using sodium azide and various carbon sources

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-6-44-55

Abstract

The main properties of the highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC composition are presented, demonstrating the potential for using nitride-carbide composite materials across various industries. An in-situ process was employed to synthesize composite ceramics by chemically producing nitride and carbide nanoparticles directly within the composite volume. The study details the development of the technology for synthesizing the highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC composition using the azide SHS method during the combustion of mixtures of Ti, C, and sodium azide (NaN3) powders with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, (C2F4)n ) serving as an activating and carbiding additive. Thermodynamic calculations of these reactions showed that the adiabatic temperatures were sufficiently high to sustain a self-propagating combustion mode. Experimental investigations into the microstructure and phase composition of the combustion products are also presented. The synthesized compositions consist of highly dispersed equiaxed particles, which include a mixture of nanosized (less than 100 nm) and submicron (100–500 nm) particles of titanium carbide and nitride, as well as silicon nitride fibers with diameters of 50–200 nm and lengths of up to 5 μm. The use of PTFE as a partial replacement for carbon in the mixture during azide SHS eliminated, in most cases, the limitations of traditional approaches for achieving various ratios of target phases of Si3N4 and TiC. This enabled the synthesis of highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC powder compositions with a phase composition closely aligned with theoretical calculations. Thus, the application of the azide SHS method proved effective for obtaining highly dispersed ceramic powder compositions, including Si3N4–TiC and Si3N4–TiN–TiC.

Keywords

For citations:

Titova Yu.V., Yakubova A.F., Belova G.S. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC composition using sodium azide and various carbon sources. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2024;18(6):44-55. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-6-44-55

Introduction

Silicon nitride ceramics exhibit excellent mechanical and thermal properties, making them an ideal material for high-temperature applications such as aerospace structural components and turbine engines [1]. Their microstructure after sintering resembles that of composites reinforced with β-Si3N4 whiskers, which act as reinforcing elements [2–4]. Adequate fracture toughness, high hardness, and good wear resistance are critical characteristics for advanced ceramics, which find applications in cutting tools and automotive components such as cam rollers and ball bearings in diesel engines [5–7]. Recently, silicon nitride ceramics have attracted significant interest due to their high mechanical properties, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance [8–12]. Thermal shock resistance is a key property for their high-temperature applications. However, most studies on silicon nitride nanocomposites focus on optimizing fracture toughness and flexural strength. To expand the application areas of silicon nitride ceramics, improvements in shock resistance and high-temperature creep resistance are essential [13].

Considerable efforts have been made to improve the mechanical properties of Si3N4 by controlling the microstructure or creating various types of composites. During the densification process, β-Si3N4 fibers significantly increase fracture toughness as cracks interact with these large grains [14].

Tensile strength is widely recognized as one of the most important factors for enhancing the thermal stability of ceramics [15; 16]. Incorporating second-phase particles into a ceramic matrix can enhance the mechanical properties of ceramics. Studies have also shown that the addition of a secondary phase can improve crack initiation and propagation resistance in various ways [17–20]. For example, adding TiC particles to a silicon nitride matrix enhances mechanical performance, thermal shock behavior, and fatigue resistance, with an optimal TiC content of 10 wt. % [13]. Other researchers [21–23] have also reported the influence of TiC particles on the Si3N4 matrix.

Moreover, silicon nitride is extremely hard and non-conductive, making machining with conventional diamond tools challenging and costly, significantly increasing the final cost of ceramic components. Consequently, new electrically conductive composites based on silicon nitride have been developed for more cost-effective electrical discharge machining by incorporating certain amounts of electrically conductive particles such as TiC, TiN, or TiCN into the ceramic matrix [24; 25]. For instance, a Si3N4 + TiN composite with critical TiN content can be machined using inexpensive electrical discharge machining [26].

A Si3N4–TiC nanocomposite with high mechanical properties was obtained by hot pressing with the addition of 10 wt. % nanosized Si3N4 particles and 15 wt. % TiC to a submicron Si3N4 matrix, using Al2O3 and Y2O3 as sintering aids. Layered composites demonstrated high strength, fracture toughness, and wear resistance due to the presence of compressive surface stresses in the layers. A ceramic nanocomposite Si3N4–TiC was fabricated using a Si3N4 micro-matrix with nanosized Si3N4 and TiC particles. Cutting tools made from this ceramic exhibited better wear resistance than those made from sialon. Wear occurred mainly through abrasion and adhesion, whereas sialon cutting tools predominantly experienced abrasion, adhesion, thermal cracking, and delamination [27; 28].

The addition of secondary phases, namely the production of composites with ceramic matrices, offers many significant advantages, such as improved fracture toughness compared to unreinforced ceramics [29; 30]. Moreover, recent studies have shown that in-situ phase formation provides additional opportunities compared to composites produced using traditional ex-situ methods. The main advantages of in-situ manufacturing methods include enhanced mechanical properties, the ability to achieve unique microstructures, process simplicity, and inexpensive raw materials [27].

One promising in-situ technology is the self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) process, which enables the production of a wide range of refractory compounds, including nitrides and carbides, by utilizing the heat released during combustion in simple, compact equipment with short processing times [30].

To produce highly dispersed (d < 1 μm) Si3N4–TiC powder compositions, the authors of this article investigated the use of azide synthesis, a variation of SHS where sodium azide (NaN3) powder serves as the nitriding agent, and various activating halide salts are used alongside elemental reactants. This approach results in relatively low combustion temperatures, the formation of numerous intermediate vapor-gas reaction products, and final by-products consisting of condensed and gaseous phases. These by-products separate the target powder particles and prevent their agglomeration into larger particles.

The study summarizes the results of azide SHS synthesis of Si3N4–TiC ceramic compositions with various nitride-to-carbide phase ratios of Si3N4:TiC = 4:1, 2:1, 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4, according to the following stoichiometric equations, using halide salts such as Na2SiF6 and (NH4 )2SiF6 [33; 34].

Si–Ti–NaN3–Na2SiF6–C system

| 11Si + Ti + 4NaN3 + Na2SiF6 + C = 4Si3N4 + TiC + 6NaF, | (1) |

| 5Si + Ti + 4NaN3 + Na2SiF6 + C = 2Si3N4 + TiC + 6NaF + 2N2 , | (2) |

| 2Si + Ti + 4NaN3 + Na2SiF6 + C = Si3N4 + TiC + 6NaF + 4N2 , | (3) |

| 2Si + 2Ti + 4NaN3 + Na2SiF6 + 2C = Si3N4 + 2TiC + 6NaF + 4N2 , | (4) |

| 2Si + 4Ti + 4NaN3 + Na2SiF6 + 4C =Si3N4 + 4TiC + 6NaF + 4N2 . | (5) |

Si–Ti–NaN3–(NH4 )2SiF6–C system

| 11Si + Ti + 6NaN3 + (NH4)2SiF6 + C = 4Si3N4 + TiC + 6NaF + 4H2 + 2N2 , | (6) |

| 5Si + Ti + 6NaN3 + (NH4)2SiF6 + C = 2Si3N4 + TiC + 6NaF + 4H2 + 6N2 , | (7) |

| 2Si + Ti + 6NaN3 + (NH4)2SiF6 + C = Si3N4 + TiC + 6NaF + 4H2 + 8N2 , | (8) |

| 2Si + 2Ti + 6NaN3 + (NH4)2SiF6 + 2C = Si3N4 + 2TiC + 6NaF + 4H2 + 8N2 , | (9) |

| 2Si + 4Ti + 6NaN3 + (NH4)2SiF6 + 4C = Si3N4 + 4TiC + 6NaF + 4H2 + 8N2 . | (10) |

In these stoichiometric reactions, the composition of the reaction products is expressed in moles. When converted to weight percent (wt. %), the following ratios are obtained for the expected theoretical composition of the target Si3N4–TiC compositions after the removal of the water-soluble byproduct salt, NaF, from the condensed reaction products:

| (1), (6) | 4Si3N4 + TiC = 90.4 % Si3N4 + 9.6 % TiC, |

| (2), (7) | 2Si3N4 + TiC = 82.4 % Si3N4 + 17.6 % TiC, |

| (3), (8) | Si3N4 + TiC = 70.1 % Si3N4 + 29.9 % TiC, |

| (4), (9) | Si3N4 + 2TiC = 53.9 % Si3N4 + 46.1 % TiC, |

| (5), (10) | Si3N4 + 4TiC = 36.9 % Si3N4 + 63.1 % TiC. |

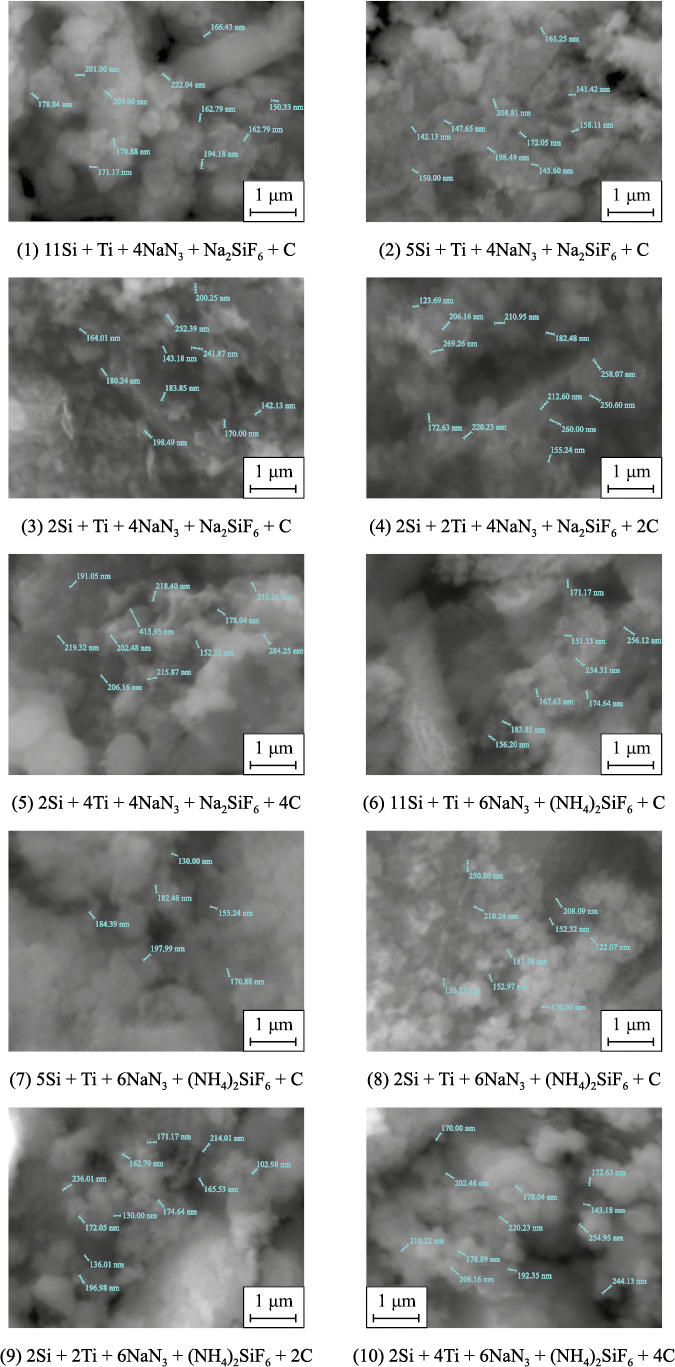

The results of the phase composition analysis of the washed solid combustion products from reactions (1)–(10), determined experimentally, are presented in Table 1. In most cases, the products consist of a highly dispersed powder with a complex composition, appearing as submicron equiaxed particles ranging in size from 100 nm to 1 μm (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Experimental phase composition of washed solid products from azide SHS

Fig. 1. Microstructure of combustion products from charges according to equations (1)–(10) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From the data in Table 1, it is evident that the experimental phase composition of the products from azide SHS differs significantly from the expected theoretical composition of Si3N4–TiC powder compositions. The content of the target carbide phase TiC is significantly lower than its theoretical value (ranging from 2.7 to 19.9 %), the amount of Si3N4 is excessive, and an undesirable secondary phase, titanium nitride, is present (ranging from 1.9 to 19.2 %). These results can be attributed to the fact that very fine and lightweight particles of technical carbon may be partially or completely removed from the burning, highly porous bulk charge sample by gases released during the decomposition of sodium azide and halide salts, preventing their participation in the formation of titanium carbide. As a result, silicon nitride forms in larger quantities, and titanium nitride forms due to an excess of nitrogen (since combustion in a nitrogen atmosphere is essential for in-situ nitride formation in SHS compositions), while titanium carbide forms in smaller amounts than predicted by the initial stoichiometric reaction equations and thermodynamic calculations. Additionally, the synthesized compositions may contain impurities of unreacted free silicon (up to 1.9 %) or carbon (up to 1.5 %).

To address these shortcomings, several directions for further research on applying the SHS process to produce highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC compositions can be pursued. The simplest approach is to use polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE (C2F4 )n ) as an activating and carbon-containing additive in the charge, promoting the formation of TiC, as successfully demonstrated in previous studies [35; 36].

In this context, the aim of the present study was to maximize the convergence of the theoretical and experimental compositions of the Si3N4–TiC powder composition by modifying the initial reactant composition with full or partial replacement of carbon with PTFE and optimizing the conditions of the azide SHS process.

Research methodology

To synthesize the target Si3N4–TiC composition with phase molar ratios ranging from 2:1 to 1:4, chemical reaction equations involving full (11)–(14) and partial (15), (16) substitution of carbon with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) were used:

| 12Si + 2Ti + 4NaN3 + C2F4 + 3.25N2 = 4Si3N4 + 2TiC + 4NaF + 1.25N2 , | (11) |

| 6Si + 2Ti + 4NaN3 + C2F4 = 2Si3N4 + 2TiC + 4NaF + 2N2 , | (12) |

| 3Si + 2Ti + 4NaN3 + C2F4 = Si3N4 + 2TiC + 4NaF + 4N2 , | (13) |

| 3Si + 4Ti + 8NaN3 + 2C2F4 = Si3N4 + 4TiC + 8NaF + 10N2 , | (14) |

| 3Si + 2Ti + 0.32NaN3 + 1.84C + 0.08C2F4 +1.52N2 = Si3N4 + 2TiC + 0.32Na, | (15) |

| 3Si + 4Ti + 0.64NaN3 + 3.68C + 0.16C2F4 +1.04N2 = Si3N4 + 4TiC + 0.64NaF. | (16) |

To achieve the Si3N4–TiC composition with the maximum titanium carbide phase content (Si3N4:TiC = 1:4), carbiding mixtures with increased PTFE content were also used:

| 3Si + 4Ti + 0.8NaN3 + 3.6C + 0.2C2F4 + 0.8N2 = Si3N4 + 4TiC + 0.8NaF, | (17) |

| 3Si + 4Ti + 1.6NaN3 + 3.2C + 0.4C2F4 = Si3N4 + 4TiC + 1.6NaF + 0.4N2 , | (18) |

| 3Si + 4Ti + 2.4NaN3 + 2.8C + 0.6C2F4 = Si3N4 + 4TiC + 2.4NaF + 1.6N2 . | (19) |

Thermodynamic calculations were conducted using the Thermo software [37] to predict the feasibility of combustion reactions by determining thermal effects (enthalpies), adiabatic temperatures, and the compositions of synthesis products.

The following raw materials were used in the experiments:

– silicon powder, grade Kr0 (main substance content ≥98.8 wt. %, average particle size d = 5 μm;

– titanium powder, grade PTOM-1 (98.0 wt. %, d = 30 μm);

– sodium azide powder, analytical grade (≥98.71 wt. %, d = 100 μm);

– carbon black, grade P701 (≥99.7 wt. %, d = 70 nm, agglomerates up to 1 μm);

– polytetrafluoroethylene, grade PN-40 (≥99.0 %, d = 40 μm).

Combustion of the starting reactant mixtures (charge) with a bulk relative density of 0.4 was conducted in a paper crucible with a diameter of 30 mm and a height of 45 mm. The experiments were performed in a laboratory SHS-Az reactor with a volume of 4.5 L, equipped with two thermocouples, under a nitrogen pressure of 4 MPa. The thermocouples were used to measure combustion temperatures and calculate the combustion rate. The pressure variation in the reactor during the combustion process was monitored with a pressure gauge.

The synthesized product was weighed and compared to the theoretical yield calculated from reactions (11)–(19). The combustion product was washed with water to remove water-soluble impurities, and the pH of the wash water was measured to assess the presence of free sodium in the combustion product and the completeness of the chemical reaction. The phase composition of the synthesized combustion products was determined using an automated ARL X’trA X-ray diffractometer (Thermo Scientific, Switzerland). CuKα radiation was employed with continuous scanning over the angular range of 2θ = 20–80° at a scan rate of 2°/min. The resulting spectra were processed using the WinXRD software package. The surface topography and powder particle morphology were examined using a JSM-6390A scanning electron microscope (Jeol, Japan) equipped with a Jeol JED-2200 energy-dispersive spectroscopy attachment.

Results and discussion

The results of thermodynamic calculations for reactions (11)–(19) performed using the Thermo software are presented in Tables 2–4.

Table 2. Thermodynamic analysis results for reactions (11)–(14)

Table 3. Thermodynamic analysis results for reactions (15), (16)

Table 4. Results of thermodynamic analysis of reactions (17)–(19)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From the presented data, it is evident that all reactions exhibit high adiabatic temperatures sufficient for the realization of the SHS process in a combustion mode. The reaction products contain all the phases corresponding to the right-hand sides of equations (11)–(19), including the target phases of silicon nitride (Si3N4 ) and titanium carbide (TiC), the water-soluble byproduct salt NaF, and minor impurities of free silicon (Si) and titanium (Ti).

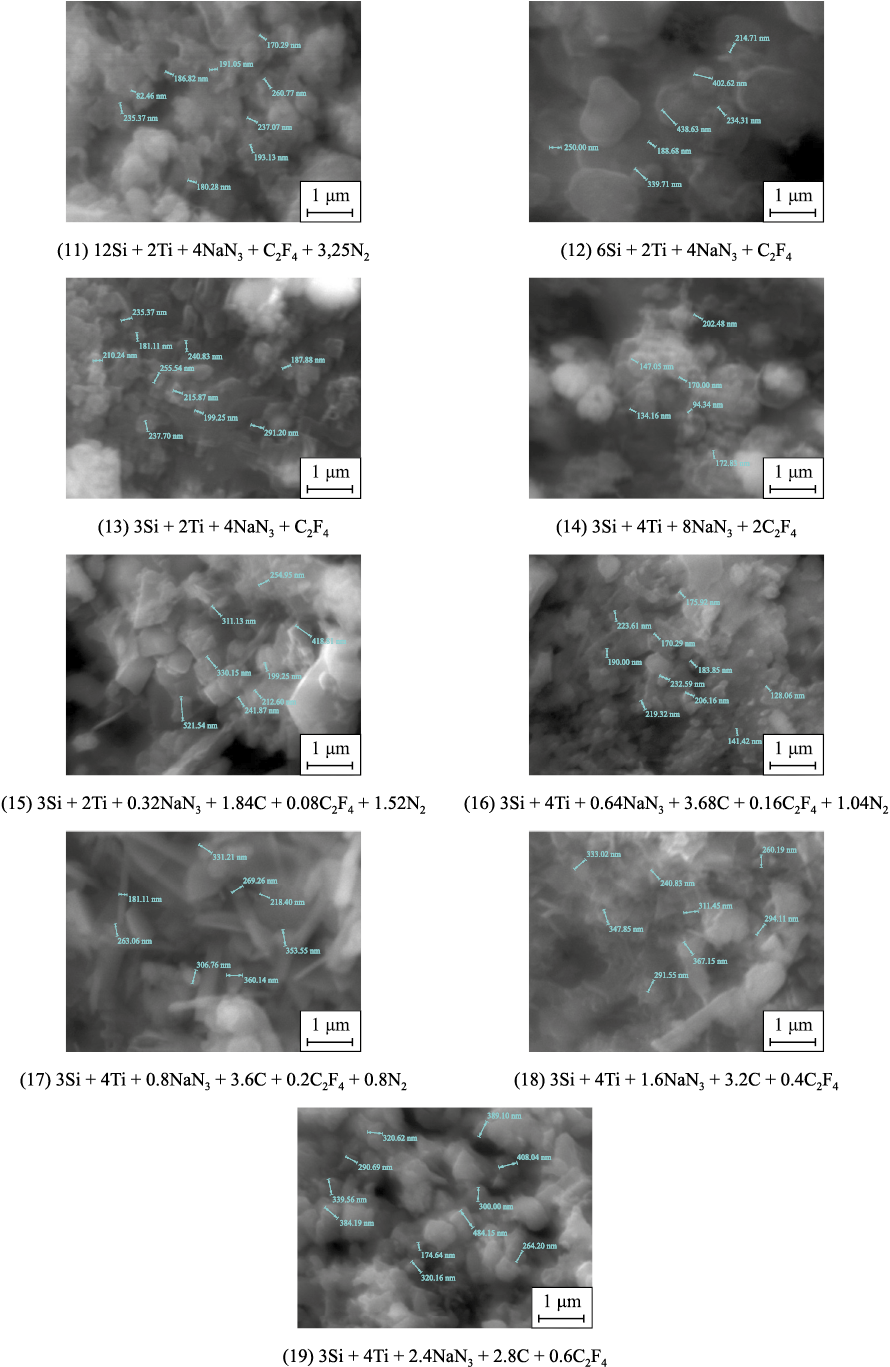

The results of the microstructural analysis of the combustion products of the initial powder mixtures (charges) from reactions (11)–(19) after washing with water to remove the byproduct salt NaF are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Microstructure of combustion products from charges according to equations (11)–(19) |

As shown in Fig. 2, the combustion products of charges from reactions (11)–(19) consist of highly dispersed equiaxed particles, comprising a mixture of nanosized (less than 100 nm) and submicron (100–500 nm) particles of titanium carbide and titanium nitride, as well as silicon nitride fibers with diameters of 50–200 nm and lengths of up to 5 μm.

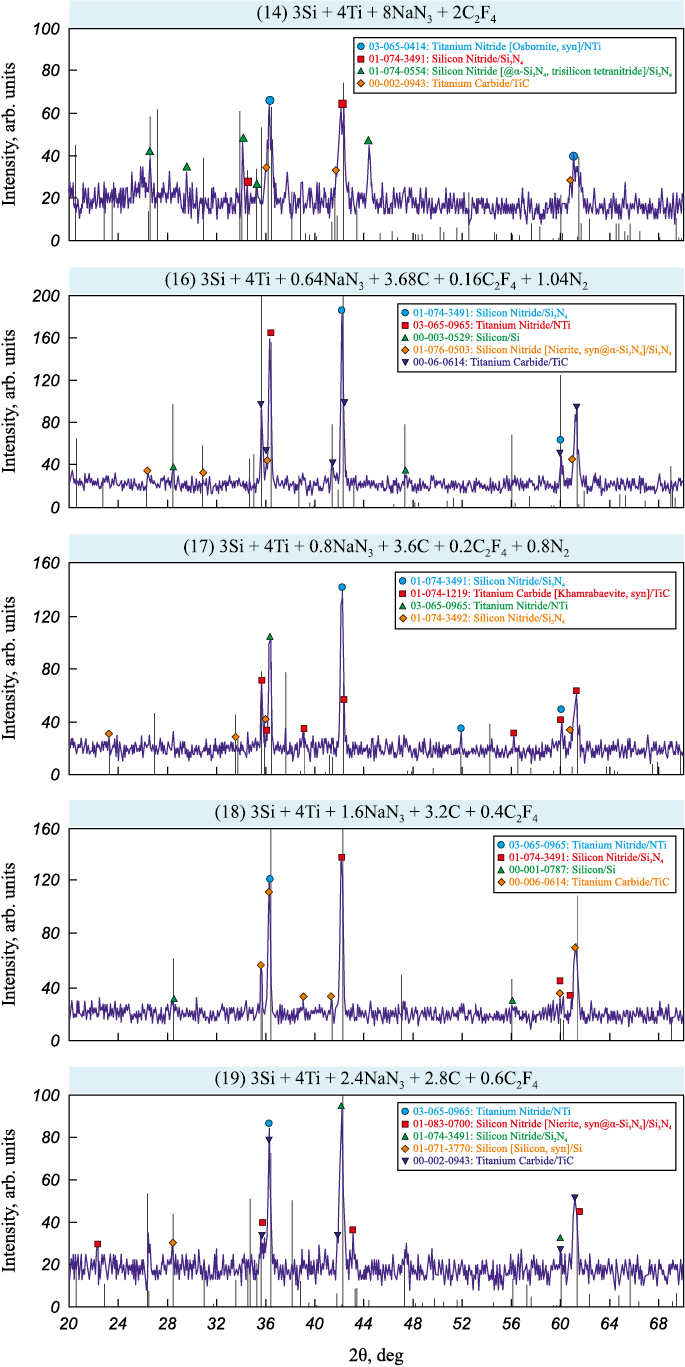

The results of X-ray phase analysis for the washed combustion products of systems with the maximum titanium carbide phase content (Si3N4 :TiC = 1:4) are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. X-ray diffraction patterns of combustion products from charges (14), (16)–(19) |

The results of quantitative processing of the XRD spectra presented in Fig. 3 are summarized in Table 5. These results show the phase content in the washed combustion products of charges with the maximum titanium carbide phase fraction (Si3N4:TiC = 1:4) under various conditions: full replacement of carbon black with PTFE (reaction 14), carbiding mixtures with minimal PTFE content (reaction 16), and carbiding mixtures based on reactions (17)–(19) to synthesize the Si3N4–TiC composition. The experimental data are compared with theoretical phase compositions of target products Si3N4 and TiC based on the stoichiometric equations (11)–(19).

Table 5. Theoretical and experimental phase compositions

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From the data in Table 5, it is evident that using PTFE as a carbon source for synthesizing nitride-carbide compositions via azide SHS is a promising research direction. A comparison of the experimental phase compositions of combustion products from charges (11)–(14) with theoretical values indicates that full replacement of carbon black with PTFE is not advisable, although the titanium carbide phase content increases compared to azide SHS without PTFE. For example, the titanium carbide content in the combustion products of charge (5): 2Si + 4Ti + 4NaN3 + Na2SiF6 + 4C with the maximum TiC content (Si3N4:TiC = 1:4), is 19.9 wt. %. With full replacement of carbon black by PTFE in charge: 3Si + 4Ti + 8NaN3 + 2C2F4 ) the titanium carbide content increases to 31.0 wt. %. However, partial replacement of carbon black and its combined use with PTFE as a carbon source allows the titanium carbide content to reach 52.3 wt. % in the combustion products of charge (16): 3Si + 4Ti + 0.64NaN3 + 3.68C + 0.16C2F4 + 1.04N2 .

The best results were obtained using carbiding mixtures with increased PTFE content according to equations (17)–(19), where the TiC content in the experimental products ranged from 58.6 to 61.7 wt. %. Furthermore, the use of PTFE reduced the content of the secondary phase, titanium nitride, to 2.0–4.0 wt. % in the products of carbiding mixtures (17)–(19).

Conclusion

The presented results demonstrate that the SHS technology can make a significant contribution to the development of methods for producing highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC nitride-carbide compositions. The SHS process is attractive for its simplicity and cost-effectiveness and is one of the promising in-situ chemical methods for the direct synthesis of ceramic powders within the desired composition from a mixture of inexpensive starting reagents.

Traditional azide SHS using NaN3 and gasifying halide fluorides, such as Na2SiF6 and (NH4)2SiF6 , is characterized by comparatively low combustion temperatures, the formation of large amounts of intermediate vapor and gaseous reaction products, as well as final byproduct condensed and gaseous products that separate the target powder particles. This enabled the synthesis of a highly dispersed (<1 μm) Si3N4–TiC powder composition, with Si3N4 predominantly in the α-modification phase during the combustion of all studied mixtures.

However, in all cases of traditional azide SHS application, the amount of TiC phase synthesized in the experiments was significantly lower than expected. Additionally, all synthesized compositions contained the TiN phase, with its content exceeding that of titanium carbide in mixtures without PTFE additives. Furthermore, the synthesized compositions may include impurities of unreacted free silicon (up to 3.0 wt. %).

The use of PTFE as an activating and carbiding additive with partial replacement of carbon in the mixtures (15)–(19) in azide SHS eliminated, in most cases, the shortcomings of the traditional approach for various ratios of target phases Si3N4 and TiC. This allowed for the synthesis of highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC powder compositions with a phase composition significantly closer to the calculated theoretical composition.

References

1. Schioler L.J. Heat engine ceramics. American Ceramic Society Bulletin. 1985;64(2):268–294.

2. Ding S., Zeng Y.P., Jiang D. Oxidation bonding if porous silicon nitride ceramics with high strength and low dielectric constant. Materials Letters. 2007;6(11-12):2277–2280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2006.08.067

3. Huang Zh., Chen F., Su R., Wang Zh., Li J., Shen Q., Zhang L. Electronic and optical properties of Y-doped Si3N4 , by density functional theory. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2015;637(15):376–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.02.213

4. Kim S., Park B.G. Tuning tunnel barrier in Si3N4-based resistive memory embedding SiO2 , for low-power and high-density cross-point array applications. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2016;663:256–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.12.107

5. Qi G., Zhang C., Hu H. High strength three-dimensional silica fiber reinforced silicon nitride-based composites via poly hydridomethylsilazane pyrolysis. Ceramics International. 2007;33(5):891–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2006.01.018

6. Barta J., Manela M., Fischer R. Si3N4 and Si2N2O for high performance randomes. Materials Science and Engineering. 1985;71:265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5416(85)90236-8

7. Riley F.L. Silicon nitride and related materials. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2000;83(2):245–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01182.x

8. Niihara K. New design concept of structural ceramic–ceramic nanocomposites. Journal of the Ceramic Society of Japan. 1991;99(10):974–982. https://doi.org/10.2109/jcersj.99.974

9. Hirai H., Hondo K. Shock-compacted Si3N4 nano-crystalline ceramic. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 1994;77(2):487–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1994.tb07018.x

10. Vaben R., Stover D. Processing and properties of nanophase nonoxide ceramics. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2001;301(1):59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5093(00)01389-7

11. Steritzke M. Review: Structural ceramic nanocomposites. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 1997; 17(9):1061–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-2219(96)00222-1

12. Gasch M.J., Wan J., Mukherjee A.K. Preparation of a Si3N4/SiC nanocomposite by high-pressure sintering of polymer precursor derived powders. Scripta Materialia. 2001;45(9):1063–1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(01)01140-X

13. Tian Ch., Liu N., Lu M. Thermal shock and thermal fatigue behavior of Si3N4–TiC nano-composites. International Journal of Refractory Metals & Hard Materials. 2008;26(5):478–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2007.11.004

14. Ziegler G. Thermal properties and thermal shock resistance of silicon nitride. In: Progress in nitrogen ceramics. F.L. Riley Ed. Boston: Martinus Nihoff Publ., 1983. Р. 565–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-6851-6

15. Hirosaki N., Okamoto Y., Akimune Y., Mitomo M. Sintering of Y2O3–Al2O3 doped β-Si3N4 powder and mechanical properties of sintered materials. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 1978;61(3-4):114–118. https://doi.org/10.2109/JCERSJ.102.790

16. Clarke D.R., Thomas G. Microstructure of Y2O3 fluxed hot-pressed silicon nitride. Acta Metallurgica et Materialia. 1995;43(3):923–930. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1978.tb09251.x

17. Hirano T., Niihara K. Thermal shock resistance of Si3N4/SiC nanocomposites fabricated from amorphous Si–C–N precursor powders. Materials Letters. 1996; 26(6):285–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-577X(96)80001-2

18. Pettersson P., Johnsson M. Thermal shock properties of alumina reinforced with Ti(C,N) whiskers. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2003;23(2):309–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-2219(02)00177-2

19. Ebrabimi M.E., Chevalier J., Fantozzi G. Slow crack growth behavior of alumina ceramics. Journal of Materials Research. 2000;15(1):142–147. https://doi.org/10.1557/JMR.2000.0024

20. Hirata T., Katsunori A., Yamamotto H. Sintering behavior of Cr2O3–Al2O3 ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2000;20(2):195–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-2219(99)00161-2

21. Szafran M., Bobryk E., Kukla D., Olszyna A. Si3N4–Al2O3–TiC–Y2O3 composites intended for the edges of cutting tools. Ceramics International. 2000;26(6):579–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-8842(99)00098-X

22. Ling B., Ge Ch., Shen W., Mao X., Zhang K. Densification, microstructure, and fracture behavior of Si3N4–TiC composites by spark plasma sintering. Rare Metals. 2008;27(3):315–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0521(08)60136-9

23. Buljan S.T., Zilberstein G. Effect of impurities on microstructure and mechanical properties of Si3N4–TiC composites. In: Tailoring Multiphase and Composite Ceramics. US. Springer, 1986. Р. 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-2233-7_23

24. Martin C., Cales B., Vivier P., Mathieu P. Electrical discharge machinable ceramic composites. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 1989;109:351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-5093(89)90614-X

25. Gogotsi G. Particulate silicon nitride-based composites. Journal of Materials Science. 1994;29(10):2541–2556. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00356803

26. Wang C.M. Microstructure development of Si3N4-TiN composite prepared by in situ compositing. Journal of Materials Science. 1995;30(12):3222–3230. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01209241

27. Singh V., Bansal A., Jindal M., Sharma P., Singla A.K. Slurry erosion resistance, morphology, and machine learning modeling of plasma-sprayed Si3N4 + TiC + VC and CrNi based ceramic coatings. Ceramics International. 2024;50(16):27961–27973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.05.092

28. Ye Ch., Yue X., Ru H., Long H., Gong X. Effect of addition of micron-sized TiC particles on mechanical properties of Si3N4 matrix composites. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2017;709:165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.03.124

29. Xing Y., Deng J., Feng X., Yu Sh. Effect of laser surface texturing on Si3N4/TiC ceramic sliding against steel under dry friction. Materials and Design. 2013;52:234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2013.05.077

30. Han J.-C., Chen G.-Q., Du Sh.-Y., Wood J.V. Synthesis of Si3N4–TiN–SiC composites by combustion reaction under high nitrogen pressures. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2000;20(7):927–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-2219(99)00230-7

31. Bichurov G.V. Halides in SHS azide technology of nitrides obtaining. In: Nitride Ceramics: Combustion synthesis, properties, and applications. Weinheim: Wiley, 2015. Р. 229–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527684533.ch8

32. Amosov A.P., Titova Yu.V., Belova G.S., Maidan D.A., Minekhanova A.F. SHS of highly dispersed powder compositions of nitrides with silicon carbide. Review. Powder Metallurgy and Functional Coatings. 2022;16(4):34–57. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2022-4-34-57

33. Titova Yu.V., Belova G.S., Yakubova A.F. Application of combustion of Ti–Si–NaN3–Na2SiF6–C powder mixture for the synthesis of highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC ceramic composition. In: Proceeding of the International Conference on Physics and Chemistry of Combustion and Processes in Extreme Environments (Samara, Russia, 2–6 July 2024). Samara: Publishing OOO “Insoma-Press”. 2024. Р. 60.

34. Titova Y.V., Belova G.S., Yukubova A.F. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of Si3N4–TiC composition using sodium azide. In: Proceeding of 9th International Congress on Energy Fluxes and Radiation Effects (EFRE-2024). Tomsk: Academizdat, 2024. Р. 583.

35. Nersisyan G.A., Nikogosov V.N., Kharatyan S.L. Thermal regimes for carbidizing wave propagation in the system titanium-halogen-containing polymer. Combustion Explosion and Shock Waves. 1992;28(3):251–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00749638

36. Kharatyan S.L., Nersisyan H.H. Chemically activated SHS in synthesis of refractory carbide powders. Key Engineering Materials. 2002;217:83–92. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.217.83

37. Rogachev A.S., Mukasyan A.S. Combustion for material synthesis. New York: CRC Press., 2014. 422 р.

About the Authors

Yu. V. TitovaRussian Federation

Yuliya V. Titova – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor at the Department of Metallurgy, Powder Metallurgy, Nanomaterials

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

A. F. Yakubova

Russian Federation

Alsu F. Yakubova – Postgraduate Student, Department of Metallurgy, Powder Metallurgy, Nanomaterials

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

G. S. Belova

Russian Federation

Galina S. Belova – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor at the Department of Metallurgy, Powder Metallurgy, Nanomaterials

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

Review

For citations:

Titova Yu.V., Yakubova A.F., Belova G.S. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of highly dispersed Si3N4–TiC composition using sodium azide and various carbon sources. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2024;18(6):44-55. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-6-44-55