Scroll to:

Development of novel antifriction composite materials through reinforcement of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys with highly dispersed titanium carbide ceramic phase

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-2-39-50

Abstract

Composite materials based on aluminum alloys reinforced with a highly dispersed titanium carbide phase demonstrate enhanced antifriction properties, allowing them to be classified as promising tribotechnical materials. One of the most accessible and efficient methods for producing such composites is Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis (SHS), which relies on the exothermic reaction between titanium and carbon precursors directly in the aluminum melt. This process enables the synthesis of a carbide phase with particle sizes ranging from 100 nm to 2 μm. The present study investigates the set of performance and processing characteristics of composites obtained via SHS of titanium carbide in melts of the industrial piston alloys AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N, aiming to assess their potential application as antifriction materials for manufacturing engine pistons. A comparative analysis was conducted on both the base alloys and the composite materials produced from them, after heat treatment including quenching and artificial aging under heat treatment conditions ensuring maximum hardness. The results demonstrated that in the AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC composite, the wear rate decreased by a factor of 2.4, the friction coefficient decreased by a factor of 2.7, and scuff resistance improved by a factor of 1.7 compared to the matrix alloy. In the AK10M2N–10 % TiC composite, the wear rate decreased by a factor of 17 and the friction coefficient decreased by a factor of 4, while maintaining the same level of scuff resistance as the matrix alloy. Both materials exhibited thermal self-heating during friction, a thermal linear expansion coefficient at 300 °C, heat resistance at 250 °C, fluidity, and linear shrinkage comparable to those of the matrix alloys (with variations within 10 %). The obtained data support the recommendation of these composites for use in the production of cast engine pistons as replacements for the original alloys.

Keywords

For citations:

Luts A.R. Development of novel antifriction composite materials through reinforcement of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys with highly dispersed titanium carbide ceramic phase. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(2):39-50. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-2-39-50

Introduction

Antifriction materials with enhanced wear resistance are an essential component of modern mechanical engineering. These materials should have a low friction coefficient, exhibit plasticity, and ensure good running-in to the counterbody, while maintaining sufficient strength properties. Traditionally, babbitts and copper-based alloys such as brass and bronze have been widely used for these purposes. However, modern tribological assembly operating conditions necessitate reducing both the weight and cost of such materials, which has led to the increased adoption of aluminum-based antifriction materials. Replacing copper alloys with aluminum ones reduces the weight of a part of the same volume by a factor of 2.5–3.0 and significantly lowers casting costs. Aluminum alloys are easier to melt due to their lower melting point, are simpler to machine, and still possess sufficient strength and corrosion resistance. Furthermore, their high thermal conductivity helps maintain the lubricating layer at higher sliding speeds and under higher pressures [1–3].

The first aluminum-based antifriction alloys intended for bearings were developed according to the Sharpie principle, where the soft, plastic aluminum-based matrix contained intermetallic compounds (CuAl2 , FeAl3 , NiAl3 , Mg2Si, etc.) that carried the primary load and formed a favorable microrelief capable of retaining the lubricant film. Later, to prevent excessive wear of shafts, low-melting tin and lead were introduced into the alloys, forming soft structural components that migrated to the surface during operation to create a protective film. This allowed such materials to be used under conditions of boundary and dry friction [4].

The most widely used alloys for manufacturing monometallic bearings are Al–Sn–Cu system alloys, such as AO3-7 and AO9-2, while bimetallic bearings utilize AO20-1, where strength is achieved through a thin antifriction layer (0.5–1.0 mm) applied onto a strong steel backing. However, despite their good antifriction properties, these alloys lack high mechanical properties, so research in this area continues.

One approach to addressing the insufficient mechanical properties of antifriction alloys involves their modification to enhance strength characteristics by refining the grain structure [5]. However, the effect of such refinement is usually limited. For this reason, researchers more often pursue the development of complexly alloyed materials containing a range of intermetallic phases that strengthen the matrix [6–9]. Specifically, there are reports of aluminum-based antifriction materials produced by introducing Cu, Si, Zn, and Ti, as well as 8–12 % Sn1 and 2–4 % Pb into the alloy composition. Such materials meet all the requirements for sliding bearings and surpass conventional antifriction alloys like AO20-1, AO10S2, AO11S3, and bronze BrO4Ts4S17 in terms of performance [10]. A similar technology is used to produce an alloy containing Cu, Si, Zn, Mg, Ti, along with 5–11 % Sn and 2–4 % Pb. In addition to the slightly different chemical composition, this process also involves heat treatment – annealing the castings at 250–300 °C for 10–12 h. This treatment halts natural aging processes and improves both the antifriction and mechanical properties of monometallic sliding bearings [11]. However, a study [12] examining a similar Al–Cu–Si–Sn–Pb–Bi system as an antifriction alloy points out that adding more than 1 % lead and bismuth to aluminum alloys is impractical. During conventional melting and casting, there is a high risk of segregation of these elements, and their contribution to precipitation hardening through quenching and aging is insignificant. Based on this, the author of [13] recommends a base composition of Al–4 % Cu–5 % Si–6 % Sn, which offers comparable properties to expensive bronzes and should undergo the following heat treatment: holding at 500 °C for 6 h, quenching in water, and aging at 175 °C for 6 h. This treatment promotes spheroidization of the silicon phase, significantly improving both strength and wear resistance. Overall, the development of complexly alloyed materials is undoubtedly a promising direction. However, the high cost of tin and the ambiguous effect of lead and bismuth currently limit their widespread adoption.

A key trend in recent years in the production of antifriction materials is a new approach – the development of cast composite materials (CM) of this type, achieved by introducing or forming not only intermetallic phases but also ceramic phases within aluminum alloys [14–16]. Initially, silicon carbide was primarily used as the ceramic filler due to its low cost. However, studies revealed that at high temperatures and prolonged exposure, silicon carbide tends to degrade, forming undesirable phases [17]. As a result, titanium carbide has recently become the preferred filler. Firstly, titanium carbide exhibits the greatest similarity in lattice parameters to the face-centered cubic (FCC) aluminum matrix, ensuring good wettability and a modifying effect. Secondly, it is characterized by higher hardness, elastic modulus, and thermodynamic stability [18].

The first research efforts in this area in the Russian Federation were carried out using matrix alloys of the Al–Si system – the so-called silumins [19–23]. For example, in [24], antifriction composites were proposed based on AK12 and AK12M2MgN alloys, reinforced with intermetallic phases of the Al3Me type (where Me = V, Ti, Cr, Hf, Zr, Sc), introduced ceramic particles of SiC or TiC, and modified with nanoscale additives (shungite, diamond (C), TiCN, etc.). It was found that composite materials containing 5 and 10 % TiC as the reinforcing phase demonstrate lower friction coefficients and reduced wear rates compared to materials reinforced with SiC.

The advantage of using titanium carbide as a reinforcing phase was also demonstrated in a later study [25], where ready-made ceramic particles of Al2O3 , B4C, SiC, or TiC were mechanically introduced into the melts of matrix alloys belonging to various alloying systems (Al–Si–Mg, Al–Si–Cu, Al–Mg, Al–Cu–Mg, Al–Sn–Cu, etc.). Two particle size groups were investigated: d ≤ 40 μm and d = 40–100 μm. The resulting composites were then applied to steel surfaces using electric arc or plasma-powder cladding. Based on the comparison results, the authors concluded that the optimal filler is a composition with 10 % TiC and a particle size of 40–100 μm, as it provides the greatest increase in coating wear resistance – up to 10 times – and reduces the friction coefficient by 60 % compared to conventional antifriction alloys AO20-1 and B83.

Internationally, researchers are also actively developing antifriction composite materials by introducing titanium carbide into various aluminum alloys [26–30]. Reported concentrations range from as low as 0.07–0.18 vol. % [31] to more substantial levels of 5–15 wt. % [32; 33]. Studies indicate that reductions in wear rate and friction coefficient become more pronounced as the titanium carbide content increases. It is also reported that the improvement in wear resistance of CM in the presence of titanium carbide is retained at elevated temperatures of 150 and 200 °C [34]. The results of these studies have already been implemented in production. For example, the American company Martin Marietta successfully uses Al/TiCp composites to manufacture engine pistons and connecting rods [35].

Most of the ongoing research and industrial production of composite materials reinforced with titanium carbide is currently carried out using the conventional and technologically simple method of mechanically introducing pre-synthesized particles into the melt. However, the practical implementation of this method is associated with several challenges. First, the wettability of particles by the melt largely depends on the stoichiometry of TiCх , which has a wide stability range (0.55 < C/Ti ≤ 1). As the carbon content х increases, wettability decreases. Therefore, introducing a stoichiometric compound with maximum mechanical properties requires a melt temperature of at least 1400 K [36]. Second, the introduction of highly dispersed titanium carbide particles poses a challenge. Despite their higher cost, such particles have a more pronounced effect [37; 38]. For example, study [39] demonstrated that the wear resistance of Al–5 % Cu alloys containing 0.5 % of nanosized TiC particles is 16.5 % higher than that of a composite with 5 % TiC particles of micron size at the same temperature. This substantial improvement in antifriction properties is explained by the fact that, in highly dispersed particles, the number of atoms in the surface layer is comparable to the number in the particle volume, leading to fundamentally new effects and activating different strengthening mechanisms [40; 41]. However, the mechanical introduction of highly dispersed titanium carbide particles into the melt is extremely difficult, as they tend to agglomerate and exhibit poor wettability [42; 43].

These challenges can be avoided by applying a fundamentally different technological approach, namely, forming a highly dispersed carbide phase directly in the melt using the Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis (SHS) method. This involves initiating an exothermic reaction between the corresponding initial powder reagents in the heated matrix melt. Research in this area has been actively conducted by scientists in China [44–46], South Korea [47], India [48; 49], and other countries. However, the published results do not always confirm that the phase composition of the resulting materials, the amount of carbide phase, and the particle sizes meet the optimal levels required to ensure high antifriction properties.

At Samara State Technical University, intensive research has recently been carried out in this field. These efforts have led to the development of a technologically accessible method for producing composite materials, which includes four sequential stages [50; 51]:

1) heating the matrix alloy to 900 °С;

2) introducing an SHS charge into the melt, consisting of titanium and carbon powders taken in a stoichiometric ratio, as well as Na2TiF6 flux to facilitate the initiation of their exothermic interaction;

3) holding for 5 min to complete the chemical transformations, followed by melt stirring;

4) casting the composite material and its solidification.

The proposed technology features a lower melt temperature compared to mechanical mixing and a shorter process cycle, which already helps reduce production costs. Moreover, it guarantees the synthesis and uniform distribution of a highly dispersed titanium carbide phase that is fully wetted by the melt. This phase is produced directly from affordable industrial-grade titanium and carbon powders of micron size, which is also economically advantageous. The proposed method has been tested on aluminum alloys from the most common alloying systems (Al–Mg, Al–Cu, Al–Si), and it has been proven that stoichiometric titanium carbide with particle sizes ranging from 100 nm to 2 μm can be successfully synthesized in these melts. This made it possible to improve several mechanical and tribological properties of the developed composite materials [52; 53]. However, for further industrial implementation, it is necessary to consider the specific operating conditions of particular components and evaluate the required properties in combination. One of the most in-demand applications for antifriction materials is the production of cast engine pistons, which are currently made primarily from heat-resistant aluminum alloys such as AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N.

In this context, the objective of the present study was to comprehensively analyze the performance and processing characteristics of AM4.5Kd–10%TiC and AK10M2N–10%TiC composite materials produced via in-melt SHS to assess their feasibility for use as antifriction materials in engine piston manufacturing.

Materials and methods

The matrix melts were prepared using the casting alloys AM4.5Kd (GOST 1583–93) and AK10M2N (GOST 30620–98), produced by Sammet LLC, Russia. The charge mixture consisted of titanium powder (TPP-7, TU 1715-449-05785388) and carbon powder (P-701, GOST 7585–86), taken in a stoichiometric ratio to ensure the SHS reaction proceeds according to the equation: Ti + C = TiC. This mixture was combined with Na2TiF6 salt (GOST 10561–80), added in an amount of 5 % of the total charge weight. The prepared portions of the charge, wrapped in aluminum foil, were introduced into the melts of the specified alloys, heated to 900 °C in a graphite crucible placed in a PP-20/12 melting furnace (Russia). After the SHS reaction was completed and the melt was stirred, the melt containing TiC particles was cast into a metal mold to produce cast composite samples with a diameter of 20 mm and a height of approximately 150 mm. Cylindrical specimens with a diameter and height of 20 mm were then machined from these castings for further testing. All specimens underwent quenching and artificial aging to achieve maximum hardness, according to the following heat treatment conditions:

– AM4.5Kd: holding for 1 h at 545 °C, quenching, aging for 6 h at 170 °С (НВ = 136);

– AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC: holding for 1 h at 545 °C, quenching, aging for 4 h at 170 °С (НВ = 142);

– AK10M2N: holding for 2 h at 515 °C, quenching, aging for 2 h at 190 °С (НВ = 152);

– AK10M2N–10 % TiC: holding for 1 h at 515 °C, quenching, aging for 2 h at 190 °С (НВ = 171).

All heat treatment processes were performed in a SNOL laboratory chamber furnace (Russia) with a maximum operating temperature of 1300 °С.

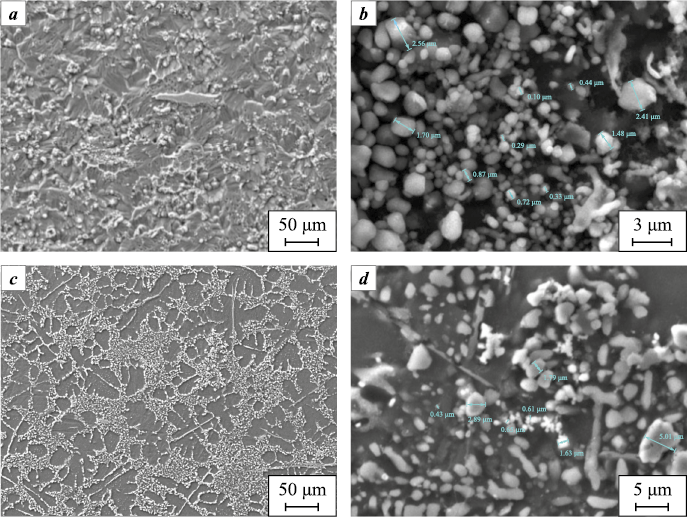

The microstructures of the heat-treated composite materials are shown in Fig. 1. According to X-ray phase analysis, in addition to titanium carbide, the AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC specimen contains 2 % of the Al2Cu phase, while the AK10M2N–10 % TiC specimen contains 2 % Al2Cu, 1 % Al3Ni, and 10 % Si.

Fig. 1. Microstructures of composite materials AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC(a, b) |

Tribological tests were performed using the Universal-1B testing system (Russia) under a ring-on-flat configuration with a lubricating medium of GL-5 transmission oil.

The thermal linear expansion coefficient (TLEC) was determined using a mechanical dilatometer on rods with an initial length of 60 mm under the following conditions: test duration – 5 h, thermocouple – type K (Chromel-Alumel), temperature range – up to 300 °C, temperature step – 25 °C. TLEC values (α, K\(^–\)1) were calculated using the formula

| \[\alpha = \frac{{{l_2} - {l_1}}}{{{l_1}({t_2} - {t_1})}},\] | (1) |

where t1 and t2 are the initial and final temperatures of the specimen, K; l1 and l2 are the corresponding specimen lengths at t1 and t2 , mm.

Short-term high-temperature strength was evaluated by compression testing at temperatures of 150 °C and 250 °C using an Instron 8802 universal testing machine (USA) equipped with a 3119-406 thermal chamber, under a load of 100 kN and a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min.

Casting properties were evaluated using the Nekhendi–Kuptsov combined casting test mold. Melts of both the alloys and composite materials, heated to 710 °C, were poured into the preheated mold (200–250 °C). Fluidity was determined based on the height of the U-shaped cast bar. Linear shrinkage (εlin , %) was calculated using the formula

| \[{\varepsilon _{{\rm{lin}}}} = \frac{{{L_{\rm{m}}} - {L_{{\rm{cast}}}}}}{{{L_{{\rm{cast}}}}}} \cdot 100{\rm{ }}\% ,\] | (2) |

where Lm = 152 mm is thelength of the vertical cavity in the mold; Lcast is the actual length of the vertical cast bar measured at t = 20 °C, mm.

Results and discussion

The antifriction properties were investigated under conditions simulating the operating environment of the piston–piston pin friction pair in an internal combustion engine at a normal load of 400 N. The rotation speed of the counterbody was 600 rpm, and the test duration was 60 min or until complete seizure occurred.

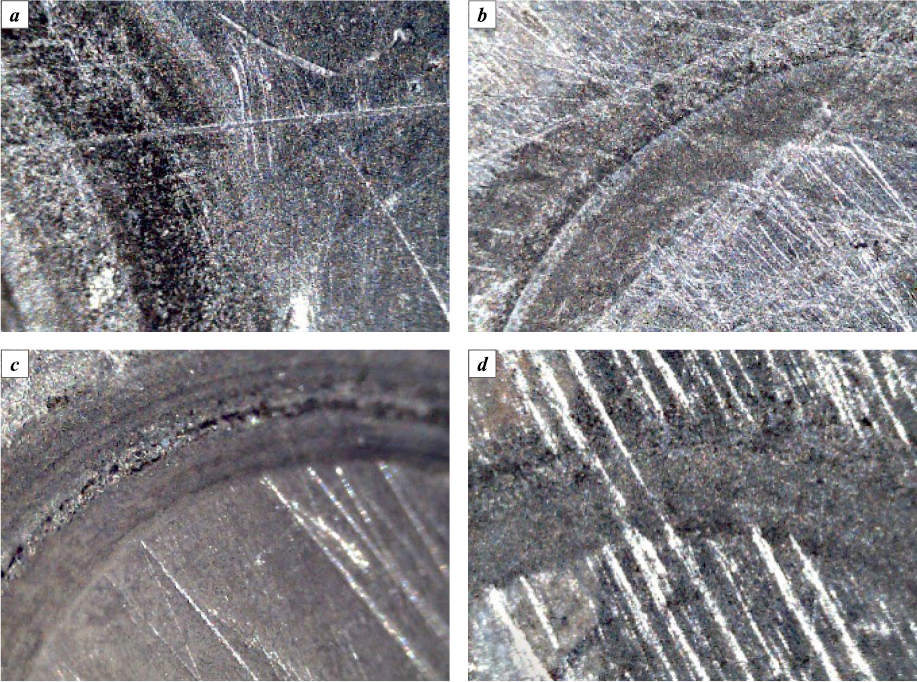

The appearance of the friction surfaces of the base alloys and the corresponding composite materials after testing is shown in Fig. 2. Analysis of the surfaces of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys indicates the presence of seizure and abrasive wear, as well as the formation of deep grooves along the sliding direction. In contrast, the surfaces of the composite materials exhibited better conformability to the counterbody and the absence of pronounced scuff marks.

Fig. 2. Appearance of friction surfaces after testing (100×) |

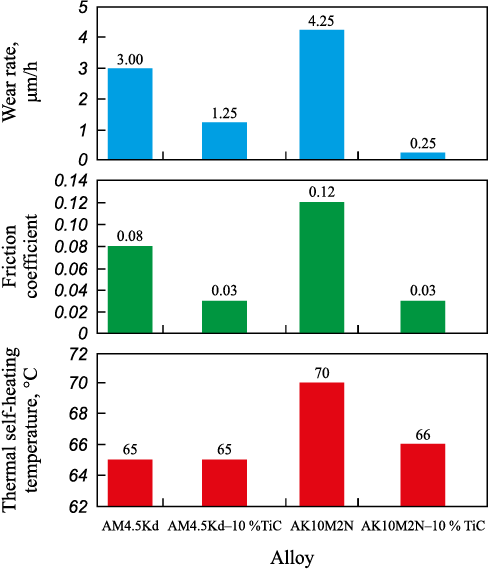

Further analysis of the friction force profiles confirmed that the presence of the titanium carbide phase significantly improved wear resistance. In the AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC composite, the wear rate decreased by a factor of 2.4, and the friction coefficient decreased by a factor of 2.7 compared to the matrix alloy. For AK10M2N–10 % TiC, the wear rate decreased by a factor of 17 and the friction coefficient decreased by a factor of 4. At the same time, the level of thermal self-heating during testing remained unchanged in both systems (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Tribological characteristics of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys |

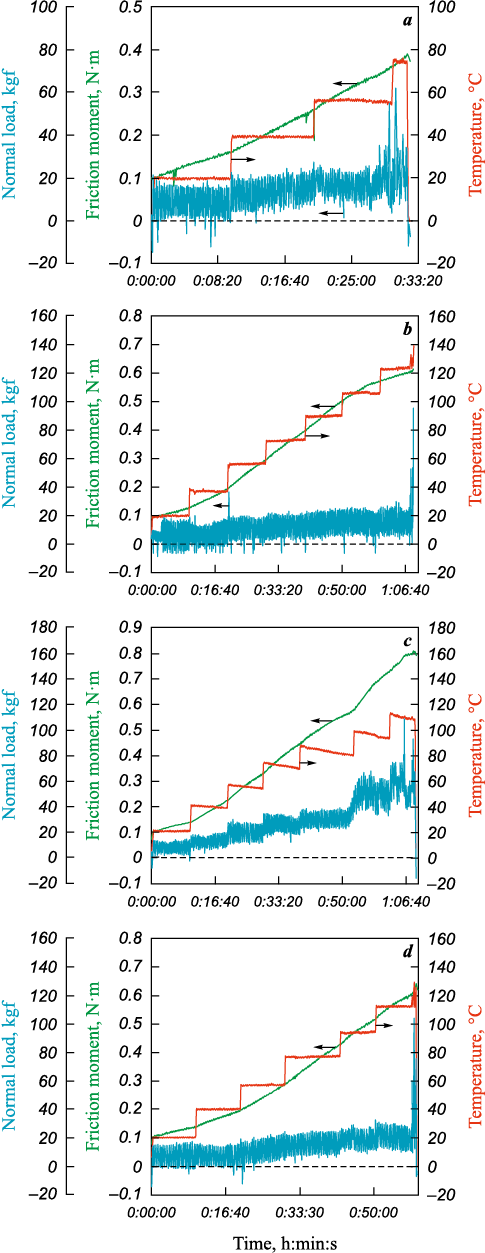

To determine the maximum permissible load, scuff resistance tests were carried out under gradually increasing load conditions. Each load stage lasted 10 min, with a load increment of 100 N, and the maximum applied load reached 1300 N. The results showed that seizure in AM4.5Kd occurred at a load of 700 N, while for the AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC composite, seizure was only observed at 1200 N – an increase by a factor of 1.7 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Friction force profiles of specimens under increasing loads |

For the AK10M2N and AK10M2N–10 % TiC specimens, complete seizure occurred at the same load of 1100 N. However, for the matrix alloy, friction coefficient fluctuations were recorded at loads above 800 N, whereas the composite specimen maintained a stable friction coefficient up to the maximum load (see Fig. 4). These results confirm the enhanced scuff resistance of both composite materials.

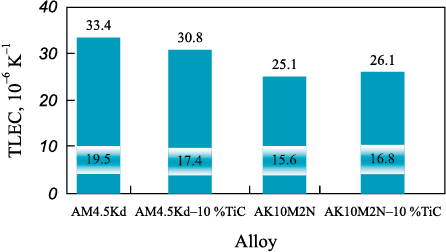

In addition to antifriction properties, another critical performance characteristic for piston materials is the ability to maintain stable linear dimensions under heating [54]. Therefore, this study also evaluated the thermal linear expansion coefficients (TLEC) of both the base alloys and the composites at temperatures of 20 and 300 °C. The analysis of the results shown in Fig. 5 reveals a slight increase in TLEC with heating for all specimens. However, the thermal expansion of the composite materials in both systems remained close to that of the matrix alloys, confirming their comparable level of thermal stability. The obtained TLEC values are consistent with the data from [55], where a composite material based on Al–5 % Cu–0.8 % Mn reinforced with 5 % B4C (particle size 5 μm) produced by mechanical mixing followed by pressure crystallization was investigated. Its TLEC was found to be 17.2·10\(^–\)6 K\(^–\)1 in the 20–100 °C range and 19.8·10\(^–\)6 K\(^–\)1 in the 20–200 °C range. That study also demonstrated that cyclic heating of the specimens did not affect the stability of these TLEC values.

Fig. 5. ТКЛР сплавов АМ4,5Кд, АК10М2Н |

The obtained data are highly significant, as it is known that the intrinsic thermal linear expansion coefficient (TLEC) of titanium carbide is higher than that of, for example, silicon carbide ((6.52–7.15)·10\(^–\)6 K\(^–\)1 and (4.63–4.7)·10\(^–\)6 K\(^–\)1, respectively). This could have potentially had a negative effect on the TLEC of the composite. Moreover, study [56] showed that increasing the particle size of the SiC fraction from 50 to 320 μm reduced the TLEC of the Al–Mg–Cu–Si–65 vol. % SiC composite material by 15–20 %. The authors attributed this to the fact that smaller silicon carbide inclusions create a larger number of interphase boundaries with unstable structures, which facilitates thermal expansion. From this perspective, the highly dispersed particles in the developed composites should also form a very large number of interphase boundaries, which could theoretically result in a significant increase in TLEC. However, this effect is not observed. Apparently, this is due to the similarity between the lattice parameters of titanium carbide and the aluminum matrix, as well as the high quality of adhesive bonding at the interphase boundaries.

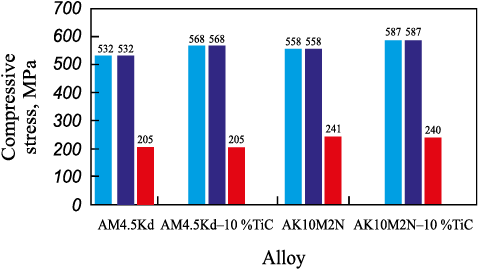

Since engine piston castings made from AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys operate at elevated temperatures (up to 250 °C) under predominantly compressive stresses, another important functional characteristic – short-term high-temperature strength – was also studied. Compression tests were carried out at elevated temperatures under a load of up to 100 kN (Fig. 6). Compared to the base alloys, both composites showed slightly higher high-temperature strength at 20 and 150 °C, which can be explained by the refractory nature of the carbide phase. At 250 °C, the composites demonstrated strength comparable to the matrix alloys, which is associated with the onset of partial melting along the matrix grain boundaries.

Fig. 6. Short-term high-temperature strength of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys |

In study [55], the temperature distribution in an operating engine piston was calculated, showing that the maximum piston temperature reaches 225 °C, with compressive stresses not exceeding 120 MPa. That same study also reported that the compressive strength of the Al–5 % Cu–0.8 % Mn–5 % B4C composite at 260 °C is 149 MPa. Comparing these results shows that the composites containing 10 % TiC provide a significantly higher safety margin for high-temperature strength under operating conditions typical for engine pistons.

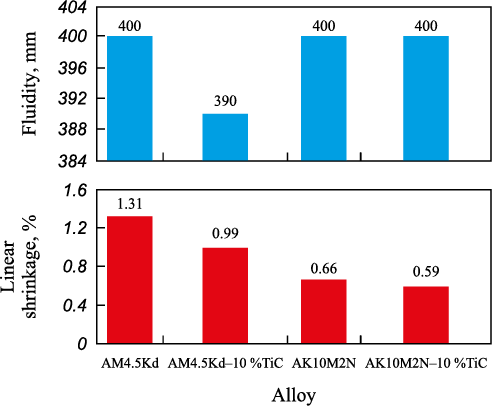

In addition to performance properties, the processing characteristics of AM4.5Kd- and AK10M2N-based composites are also critically important. The most relevant casting properties – fluidity and shrinkage – were evaluated using the Nekhendi–Kuptsov combined casting test mold (Fig. 7). During solidification, all specimens demonstrated high resistance to hot cracking. The composites of both systems also showed a general trend toward reduced linear shrinkage, which is presumably due to a slight increase in melt viscosity caused by the presence of carbide phase particles. At the same time, the high dispersity of these particles does not significantly hinder melt flow. As a result, the AM4.5Kd-based composites exhibited only a minor decrease in fluidity (>90 % of the matrix alloy’s value), while the fluidity of the AK10M2N-based composites remained virtually unchanged.

Fig. 7. Casting properties of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys |

It is generally assumed that the casting properties of composite materials deteriorate as the volume fraction of the carbide phase increases. However, study [17] examined the casting properties of AK9ch- and AK12MMgN-based composites containing 10–20 vol. % SiC, and it was found that at SiC contents of 10–15 vol. %, the composites retained high fluidity and lower linear shrinkage compared to the matrix alloys. Only at 20 vol. % SiC did fluidity decrease due to a sharp increase in melt viscosity. The high casting performance of composites containing titanium carbide particles can also be attributed to differences in TLEC. Titanium carbide has a thermal expansion coefficient that is an order of magnitude lower than aluminum ((6.52–7.15)·10\(^–\)6 K\(^–\)1 versus 2.4·10\(^–\)5 K\(^–\)1, respectively). Therefore, the presence of numerous highly dispersed block-shaped particles does not create significant resistance to melt flow, thus preserving adequate casting properties.

Conclusion

The comprehensive research conducted in this study demonstrated that synthesizing a highly dispersed titanium carbide phase directly in the melts of piston aluminum alloys AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N enables the production of new composite materials – AM4.5Kd–10 % TiC and AK10M2N–10 % TiC. These materials exhibit improved antifriction properties compared to the matrix alloys, while maintaining comparable thermal expansion during heating, high-temperature strength, and casting properties. These results provide grounds to recommend the developed composites for use in the production of cast engine pistons.

References

1. Bushe N.A., Dvoskina V.A., Rakov K.M., Gulyaev A.S. Bearings made of aluminum alloys. Moscow: Transport, 1974. 256 p. (In Russ.).

2. Mironov A.E., Kotova (Karacharova) E.G. Development of new grades of cast aluminum antifriction alloys to replace bronze in friction units. Izvestiya Samarskogo nauchnogo tsentra Rossiiskoi akademii nauk. 2011;13(4); 1136–1140. (In Russ.).

3. Menezes P.L., Ingole S.P., Nosonovsky M., Kailas S.V., Lovell M.R. Tribology for scientists and engineers. From basics to advanced concepts. NY: Springer, 2013. 948 p. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1945-7

4. Mironov A.E., Belov N.A., Stolyarova O.O. Aluminum alloys for antifriction purposes: Monograph. Moscow: MISIS, 2016. 222 p. (In Russ.).

5. Malikova E.V. Study of the possibility of modifying aluminum-tin alloy AO20-1. Vestnik TGU. 1997;2(3): 335–336. (In Russ.).

6. Neuhaus P., Roth A., Steeg M. Antifriction alloy based on aluminum: Patent 1254 (Republic Kazakhstan). 1994. (In Russ.).

7. Mironov A., Gershman I., Gershman E., Podrabinnik P., Kuznetsova E., Peretyagin P., Peretyagin N. Properties of journal bearing materials that determine their wear Resistance on the example of aluminum-based alloys. Materials. 202;14(3):535. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14030535

8. Gershman I., Mironov A., Podrabinnik P., Kuznetsova E., Gershman E., Peretyagin P. Relationship of secondary structures and wear resistance of antifriction aluminum alloys for journal bearings from the point of view of self-organization during friction. Entropy. 2019;21(11):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21111048

9. Mironov A.E., Antyukhin G.G., Gershman E.I., Podrabinnik P.A., Kuznetsova E.V., Peretyagin N.Yu. New antifriction aluminum alloys for cast monometallic plain bearings. Bench tests. Vestnik nauchno-issledovatel’skogo instituta zheleznodorozhnogo transporta. 2020;79(4):217–223. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.21780/2223-9731-2020-79-4-217-223

10. Mironov A.E., Gershman I.S., Ovechkin A.V., Kotova E.G., Koshelev M.A., Gershman E.I. Antifriction alloy based on aluminum and the method of its manufacture: Patent 2577876 (RF). 2016. (In Russ.).

11. Mironov A.E., Gershman I.S., Gershman E.I. Casting antifriction alloy based on aluminum for monometallic plain bearings and the method of its manufacture: Patent 2571665 (RF). 2015. (In Russ.).

12. Stolyarova O.O. Justification of the composition and structure of casting antifriction aluminum alloys alloyed with low-melting metals: Abstract of the Diss. Сand. Sci. (Eng.). Moscow: MISIS, 2016. 27 р. (In Russ.).

13. Stolyarova O.O., Muravyova T.I., Zagorsky D.L., Belov N.A. Microscopy in the study of the surface of antifriction multicomponent aluminum alloys. Fizicheskaya mezomekhanika. 2016;19(5):105–114. (In Russ.).

14. Rohatgi P.K., Tabandeh-Khorshid M., Omrani E., Lovell M.R., Menezes P.L. Tribology of metal matrix composites. In: Tribology for Scientists and Engineers. NY: Springer, 2013. Р. 233–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-1945-7_8

15. Wazeer A., Mukherjee A., Das A., Sengupta B., Mandal G., Sinha A. Mechanical properties of aluminium metal matrix composites: Advancements, opportunities and perspective. In: Structural Composite Materials. Composites Science and Technology. Singapore: Springer, 2024. Р. 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5982-2_9

16. Rao J.K., Madhusudhan R., Rao T.B. Recent progress in stir cast aluminum matrix hybrid composites: overview on processing, mechanical and tribological characteristics, and strengthening mechanisms. Journal of Bio- and Tribo-Corrosion. 2022;8:74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-022-00670-4

17. Aksenov A.A. Optimization of the composition and structure of composite materials on aluminum and copper bases, obtained by liquid-phase methods and mechanical alloying: Abstract of Dissertation of Dr. Sci. (Eng.). Moscow: MISIS, 2007. 51 р. (In Russ.).

18. Pan S., Jin K., Wang T., Zhang Z., Zheng L., Umehara N. Metal matrix nanocomposites in tribology: Manufacturing, performance, and mechanisms. Friction. 2022;10: 1596–1634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40544-021-0572-7

19. Kurganova Yu.A., Kolmakov A.G. Structural metal matrix composite materials: textbook. M.: MSTU im. N.E. Bauman, 2015. 141 p.

20. Prusov E.S., Panfilov A.A., Kechin V.A. Role of powder precursors in production of composite alloys using liquid-phase methods. Russian Journal of Non-Ferrous Metals. 2017;58(3):308–316. http://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821217030154

21. Prusov E.S., Deev V.B., Aborkin A.V., Ri E.K., Rakhuba E.M. Structural and morphological characteristics of the friction surfaces of in-situ cast aluminum matrix composites. Journal of Surface Investigation. 2021;15(6):1332–1337. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1027451021060410

22. Mikheyev R.S., Chernyshova T.A. Aluminum-matrix composite materials with carbide hardening for solving problems of new technology. Moscow: RFFI, 2013. 353 р. (In Russ.).

23. Mikheev R.S., Kobernik N.V., Kalashnikov I.E., Bolotova L.K., Kobeleva L.I. Tribological properties of antifriction coatings based on composite materials. Perspektivnyye materialy. 2015;3:48–54. (In Russ.).

24. Kalashnikov I.E. Development of methods for reinforcing and modifying the structure of aluminum-matrix composite materials: Abstract of the Dissertation of Dr. Sci. (Eng.). Moscow: A.A. Baikov Institute of Metallurgy of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2011. 50 р. (In Russ.).

25. Mikheev R.S. Promising coatings with improved tribotechnical characteristics made of composite materials based on non-ferrous alloys: Abstract of the Dissertation of Dr. Sci. (Eng.). Moscow: A.A. Baikov Institute of Metallurgy of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2018. 45 р. (In Russ.).

26. Lakshmikanthan A., Angadi S., Malik V., Saxena K.K., Prakash C., Dixit S., Mohammed K.A. Mechanical and tribological properties of aluminum-based metal-matrix composites. Materials. 2022;15:6111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15176111

27. Samal P., Vundavilli P.R., Meher A., Mahapatra M.M. Recent progress in aluminum metal matrix composites: A review on processing, mechanical and wear properties. Journal of Manufacturing Processes. 2020;59:131–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2020.09.010

28. Kareem A., Qudeiri J.A., Abdudeen A., Ahammed T., Ziout A. A Review on A 6061 metal matrix composites produced by stir casting. Materials. 2021;14(1):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14010175

29. Prasad C., Gali A. Microstructure, mechanical, and tribological properties of TiC- and Ni-reinforced AA6061 matrix composite fabricated through stir casting. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals. 2024;77:2625–2636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12666-024-03345-5

30. Lekatou A., Karantzalis A.E., Evangelou A., Gousia V., Kaptay G., Gacsi Z., Baumali P., Simon A. Aluminium reinforced by WC and TiC nanoparticles (ex-situ) and aluminid particles (in-situ): Microstructure, wear and corrosion behavior. Materials and Design. 2015;65:1121–1135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2014.08.040

31. Tyagi R. Synthesis and tribological characterization of in situ cast Al–TiC composites. Wear. 2005;259(1-6): 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2005.01.051

32. Liu G., Amara A.A., Eskin D., McKay B. Manufacture of nano-to-submicron-scale TiC particulate reinforced aluminium composites by ultrasound-assisted stir casting. In: Light Metals 2023. TMS 2023. The Minerals, Metals and Materials Series. Springer, 2023. P. 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22532-1_47

33. Venkateshwar Reddy P., Rajendra Prasad P., Mohana Krishnudu D., Venugopal Goud E. An investigation on mechanical and wear characteristics of Al 6063/TiC metal matrix composites using RSM. Journal of Bio- and Tribo-Corrosion. 2019;5:90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-019-0282-0

34. Jerome S. Synthesis and evaluation of mechanical and high temperature tribological properties of in-situ Al–TiC composites. Tribology International. 2010;43(11):2029–2036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2010.05.007

35. Sethi V. Effect of aging on abrasive wear resistance of silicon carbide particulate reinforced aluminum matrix composite. USA: University of Cincinnaty, 2007. 114 р.

36. Froumin N., Frage N., Polak M., Dariel M.P. Wettability and phase formation in the TiCx/Al system. Scripta Materialia. 1997;37(8):1263–1267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(97)00235-2

37. Yi G., Li H., Zang C., Xiao W., Ma C. Remarkable improvement in strength and ductility of Al–Cu foundry alloy by submicron-sized TiC particles. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2022;885:143903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2022.143903

38. Yang H., Tian S., Gao T., Nie J., You Z., Liu G., Wang H., Liu X.. High-temperature mechanical properties of 2024 Al matrix nanocomposite reinforced by TiC network architecture. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2019;763:138121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2019.138121

39. Tian W.S., Zhao Q.L., Zhao C.J., Qiu F., Jiang Q.C. The dry sliding wear properties of nano-sized TiCp /Al–Cu composites at elevated temperatures. Materials. 2017; 10(8):939. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10080939

40. Sanaty-Zadeh A. Comparison between current models for the strength of particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites with emphasis on consideration of Hall–Petch effect. Material Science and Engineering: A. 2012;531(1):112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MSEA.2011.10.043

41. Zhang Z., Chen D.L. Contribution of Orowan strengthening effect in particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites. Material Science and Engineering: A. 2008;483(15):148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2006.10.184

42. Borgonovo C., Apelian D. Manufacture of aluminum nanocomposites: A critical review. Material Science Forum. 2011;678:1–22. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.678.1

43. Rana R.S., Purohit R., Das S. Review of recent studies in Al matrix composites. International Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research. 2012;2(6):1–16.

44. Li C., Yin Y., Cao G. Effect of TiC on microstructure and strength of Al–Bi–Cu alloys. Journal. of Material Engineering and Perform. 2022;31:524–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-021-06188-z

45. Tang P., Zhou Y., Lai J. Preparation, microstructure and mechanical properties of in-situ TiC/Al–Si–Fe aluminum matrix composites. Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals. 2023;76:1893–1903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12666-023-02885-6

46. Song M.S., Huang B., Zhang M.X., Li J.G. Study of formation behavior of TiC ceramic obtained by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis from Al–Ti–C elemental powders. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2009;27(3):584–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2008.09.009

47. Cho Y.H., Lee J.M., Kim S.H. Composites fabricated by a thermally activated reaction process in an Al melt using Al–Ti–C–CuO powder mixtures. Part I: Microstructural evolution and reaction mechanism. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2014;45(12):5667–5678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-014-2476-x

48. Lingaraju S.V., Hatti G., Jadhav M.R. Investigation on tribological behavior of Al7075-TiC/Graphene nano-composite using Taguchi method. Journal of Bio- and Tribo-Corrosion. 2024;10:110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-024-00908-3

49. Sujith S.V., Mahapatra M.M., Mulik R.S. An investigation into fabrication and characterization of direct reaction synthesized Al–7079–TiC in situ metal matrix composites. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Ehgineering. 2019;19(1):63–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2018.09.002

50. Li P., Kandalova E.G., Nikitin V.I., Makarenko A.G., Luts A.R., Yanfei Zh. Preparation of Al–TiC composites by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Scripta Materialia. 2003;49(7):699–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(03)00402-0

51. Amosov A.P., Luts A.R., Latukhin E.I., Ermoshkin A.A. Application of SHS processes for in situ preparation of alumomatrix composite materials discretely reinforced by nanodimensional titanium carbide particles (review). Russian Journal of Non-Ferrous Metals. 2016;57(2):117–123. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821216020024

52. Luts A.R., Sherina Yu.V., Amosov A.P., Kachura A.D. Liquid matrix SHS manufacturing and heat treatment of Al–Mg composites reinforced with fine titanium carbide. Izvestiya. Non-Ferrous Metallurgy. 2023;29(4):70–86. https://doi.org/10.17073/0021-3438-2023-4-70-86

53. Luts A.R., Sherina Yu.V., Amosov A.P., Minakov E.A., Ibatullin I.D. Selection of heat treatment and its impact on the structure and properties of AK10M2N–10%TiC composite material obtained via SHS method in the melt. Izvestiya. Non-Ferrous Metallurgy. 2024;30(2):30–43. https://doi.org/10.17073/0021-3438-2024-2-30-43

54. Nikitin K.V., Nikitin V.I., Timoshkin I.Yu. The influence of modifiers on the change in the mechanical properties of silumins. Izvestiya. Non-Ferrous Metallurgy. 2017;3: 72–76. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/0021-3438-2017-3-72-76

55. Mostafa Ahmed Lotfi Mohammed. Structure and properties of aluminum-based composites with a low coefficient of thermal expansion: Abstract of the Diss. Сand. Sci. (Eng.). Moscow: MISIS, 2018. (In Russ.).

56. Nyafkin A.N., Shavnev A.A., Kurbatkina E.I., Kosolapov D.V. Study of the influence of silicon carbide particle size on the temperature coefficient of linear expansion of a composite material based on an aluminum alloy. Trudy VIAM. 2020;86:41–49. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.18577/2307-6046-2020-0-2-41-49

About the Author

A. R. LutsRussian Federation

Alfiya R. Luts – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Assistent Professor of the Department of Metal Science, Powder Metallurgy, Nanomaterials

244 Molodogvardeyskaya Str., Samara 443100, Russia

Review

For citations:

Luts A.R. Development of novel antifriction composite materials through reinforcement of AM4.5Kd and AK10M2N alloys with highly dispersed titanium carbide ceramic phase. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(2):39-50. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-2-39-50