Scroll to:

Grain contiguity of tungsten carbide and hardness of nanostructured and ultrafine-grained WC–(Co)–VC–Cr3C2cemented carbides fabricated by spark plasma and liquid phase sintering

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-2-51-61

Abstract

This study investigates the dependencies between contiguity and hardness in nanostructured and ultrafine-grained tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides and tungsten carbide samples fabricated using spark plasma sintering (SPS) and liquid phase sintering (LPS). The main microstructural parameters were determined: average WC grain size, grain contiguity, and mean free path in cobalt. The average WC grain size in tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides produced by spark plasma sintering does not exceed 0.2 µm, classifying them as nanostructured materials. In cemented carbides obtained by liquid phase sintering and tungsten carbide fabricated using spark plasma sintering, the average WC grain size ranges from 0.2 to 0.5 µm, which corresponds to ultrafine-grained materials. The applicability of existing models developed for medium- and fine-grained cemented carbides was analyzed to describe the dependencies of contiguity on the cobalt volume fraction in the obtained ultrafine-grained and nanostructured materials. It was found that an exponential dependence adequately describes this relationship for the samples sintered in this study. The applicability of the theoretical hardness dependence on key microstructural parameters was also analyzed. The hardness of the obtained alloys was lower than predicted by the theoretical dependence based on the Hall–Petch law. The highest hardness (HV = 2260 ± 30) among all the samples was observed in the nanostructured WC–5Co–0.4VC–0.4Cr3C2 alloy produced by spark plasma sintering. The hardness of ultrafine-grained sintered tungsten carbide was slightly lower (HV = 2250 ± 20).

Keywords

For citations:

Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A., Shichalin O.O., Buravlev I.Yu., Burkov A.A., Vlasova N.M., Chernyakov E.V., Khe V.K., Chigrin P.G. Grain contiguity of tungsten carbide and hardness of nanostructured and ultrafine-grained WC–(Co)–VC–Cr3C2cemented carbides fabricated by spark plasma and liquid phase sintering. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(2):51-61. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-2-51-61

Introduction

Tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides (WC–Co) are the most widely used tool materials in the industry for cutting applications due to their combination of hardness, strength, heat resistance, oxidation resistance, and wear resistance. The microstructure of cemented carbides is primarily characterized by the cobalt phase volume fraction (VCo) and the average WC grain size (d). In industrial practice, the most commonly used materials include medium-grained (MG) (d = 1.3–2.5 µm), fine-grained (FG) (d = 0.8–1.3 µm), and submicron-grained (SM) (d = 0.5–0.8 µm) cemented carbides. Further improvement in the operational durability of cemented carbides, which significantly depends on their hardness, remains an important task. Hardness can be increased either by reducing the cobalt content or by decreasing the average WC grain size. The latter approach is considered more promising, as it allows increasing hardness without a significant reduction in fracture toughness.

In recent decades, ultrafine-grained (UFG) cemented carbides with grain sizes reduced to 0.2–0.5 µm have gained widespread attention, offering enhanced hardness and wear resistance. Additionally, recent years have seen intensive research into the fabrication of nanostructured (NS) cemented carbides, in which the average WC grain size does not exceed 0.2 µm. It has been confirmed that these materials demonstrate high hardness, with values reported as HV = 1941 [1; 2], 1620 [3], 2356 [4], 1836 [5], and 2100 [6], resulting in improved wear resistance under abrasive wear [7] and cutting conditions. This has already led to their increasing production and application as tool and wear-resistant materials in industry. Further progress in this field requires the development of models capable of accurately describing the structure and properties of UFG and NS cemented carbides.

The main challenge in sintering such materials is grain growth caused by high temperature and prolonged sintering times. Previous studies have shown that UFG cemented carbides can be fabricated via liquid phase sintering (LPS) in vacuum [1–3; 7] or under pressure [8], using grain growth inhibitors (VC, Cr3C2 , etc.). However, these conditions are insufficient to produce nanostructured cemented carbides. In recent years, researchers have increasingly employed spark plasma sintering (SPS) [4; 9–11] for the fabrication of nanostructured and ultrafine-grained cemented carbides. During SPS, powder consolidation occurs under the action of pulsed electric currents and discharge plasma generated by spark discharges between powder particles. This process strongly enhances diffusion-controlled densification, significantly reducing the sintering time and preventing grain growth.

Maximizing hardness by reducing the cobalt content has also led to the development of sintered WC [12–16], which can only be densified to a sufficient density (>99 %) under applied pressure. SPS technology is the most effective method for producing sintered WC, as it combines the application of pressure with rapid heating, both of which help prevent excessive grain growth.

A large number of studies have investigated the microstructure and mechanical properties (primarily hardness) of UFG and NS cemented carbides, as well as sintered tungsten carbide. One of the key microstructural characteristics in these studies is contiguity, which quantifies the fraction of the specific WC grain surface area involved in WC/WC grain contacts [17]:

| \[C = \frac{{{S_{{\rm{WC/WC}}}}}}{{{S_{{\rm{WC/WC}}}} + {S_{{\rm{WC/Co}}}}}},\] | (1) |

where SWC/WC and SWC/Co denote the interfacial areas of WC/WC and WC/Co grain boundaries, respectively.

Contiguity affects the mean free path (λ) in the cobalt binder, hardness, fracture toughness, and other properties. Numerous empirical and theoretical dependencies describe the dependence of contiguity on the cobalt volume fraction in conventional tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides [4; 7; 10; 11]. However, the applicability of these dependencies to ultrafine-grained and nanostructured cemented carbides has not been confirmed.

Several models have been developed to describe the relationships between key microstructural parameters (d, VCo , C and λ) and hardness in medium-grained, fine-grained, and submicron-grained cemented carbides. Currently, there is particular interest in investigating the applicability of the dependence of hardness on key microstructural parameters [18–20] for describing the hardness of UFG and NS cemented carbides, as well as sintered tungsten carbide.

The aim of this study was to analyze the dependencies between contiguity and hardness and the microstructural parameters in UFG and NS tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides produced by liquid phase sintering and spark plasma sintering.

Materials and methods

Three nanostructured tungsten-cobalt cemented carbide samples containing 4, 5, and 10 %1 cobalt, as well as one sintered tungsten carbide (WC) sample, were fabricated using the powder metallurgy method via spark plasma sintering (SPS). Additionally, four UFG cemented carbide samples containing 6, 8, 10, and 15 % cobalt were produced using LPS technique. In cemented carbides obtained by LPS, the cobalt content must be at least 6 %, as lower cobalt concentrations make it difficult to achieve sufficient density while simultaneously limiting grain growth.

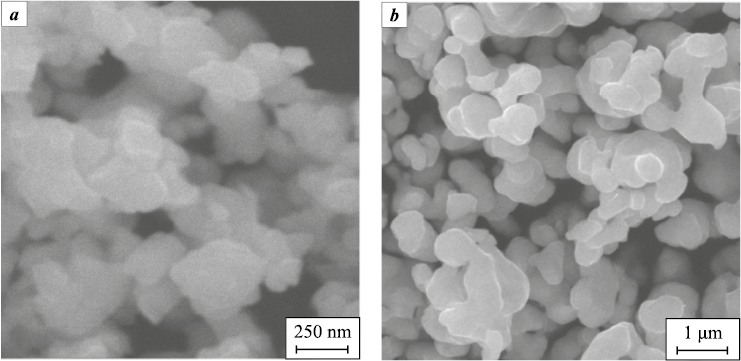

All materials were produced using nanosized tungsten carbide powder (Hongwu, China, d = 80–100 nm, purity 99.95 %) and cobalt powder (grade PK-1, Russia, GOST 9721–79, d = 1–30 µm) (Fig. 1). To suppress WC grain growth, chemically pure vanadium carbide (VC) and chromium carbide (Cr3C2 ) powders, supplied by Reohim (Russia), were added to the powder mixtures as grain growth inhibitors.

Fig. 1. Images of the initial commercial powders: tungsten carbide (a) and cobalt (b), |

The powder mixtures (Table 1), each weighing 50 g, were prepared by mixing for 1 h in a PM-400 planetary ball mill (Retsch, Germany) at a rotation speed of 250 rpm, with a ball-to-powder mass ratio of 10:1, followed by drying at 100 °C. Prior to SPS, cylindrical compacts were pre-pressed from each powder mixture (mixtures 1–4) under a pressure of 20 MPa. For mixtures 5–8, a 10 % rubber solution in gasoline was added as a plasticizer, in an amount ensuring that the granules prepared for pressing contained 1 % rubber after drying. After secondary drying to remove gasoline, four compacts were pressed from each powder mixture, with dimensions of 24×8×8 mm and a mass of 12 g.

Table 1. Compositions of cemented carbide samples, cobalt volume fraction,

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mixtures 1–4 were sintered using SPS in a graphite cylindrical die with an inner diameter of 10.5 mm on an SPS-515S system (Dr. Sinter LAB, Japan), under aconstant pressure of 57.3 MPa and a heating rate of 87.5 °C/min. To achieve the highest density, the cemented carbide samples were held at the maximum sintering temperature of 1200 °C for 5 min, while the tungsten carbide samples were held at tmax = 2000 °С for 10 min. The temperature and dwell time were selected based on previous experience with spark plasma sintering of nanostructured cemented carbides [5; 10; 15], aiming to prevent WC grain growth and avoid cobalt extrusion from the samples under applied pressure. The sintering parameters for tungsten carbide were taken from [15] to ensure the highest possible density. The compacts obtained from mixtures 5–8 underwent liquid phase sintering in a Carbolite STF vacuum furnace (Carbolite Gero, UK) at tmax = 1450 °С for 1 h to achieve high density, following the recommendations in [1–3; 7]. The compositions of the fabricated samples, sintering techniques, and maximum sintering temperatures are presented in Table 1. The cobalt volume fraction (VCo ) in the microstructure of tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides was calculated using the known densities of tungsten carbide (15.65 g/cm3) and cobalt (8.7 g/cm3), taking into account the mass concentrations of the components (see Table 1).

The density of the samples was measured by hydrostatic weighing using Vibra scales (Shinko, Japan). The surfaces of the sintered samples were ground and polished for further microstructural analysis using a Vega scanning electron microscope (Tescan Orsay Holding, Czech Republic). WC grain boundaries were revealed by etching according to Standard Method 3 of ASTM B657-92. The etchant consisted of equal parts (by weight) of 10 % potassium ferricyanide and 10 % sodium hydroxide solutions. The average WC grain size (d) and the mean free path in cobalt (λ) were determined using the linear intercept method in accordance with ASTM E112-24. The experimental WC grain contiguity was determined using the intercept method according to the formula

| \[C = \frac{{{N_{{\rm{WC/WC}}}}}}{{{N_{{\rm{WC/WC}}}} + {N_{{\rm{WC/Co}}}}}},\] | (2) |

where NWC/WC and NWC/Co are the numbers of intersections of a random test line with WC/WC and WC/Co grain boundaries, respectively.

Equations (1) and (2) are equivalent [2]. The hardness of the samples was measured using an HVS-50 hardness tester (Time Group Inc., China) under a load of 30 kgf.

Results and discussions

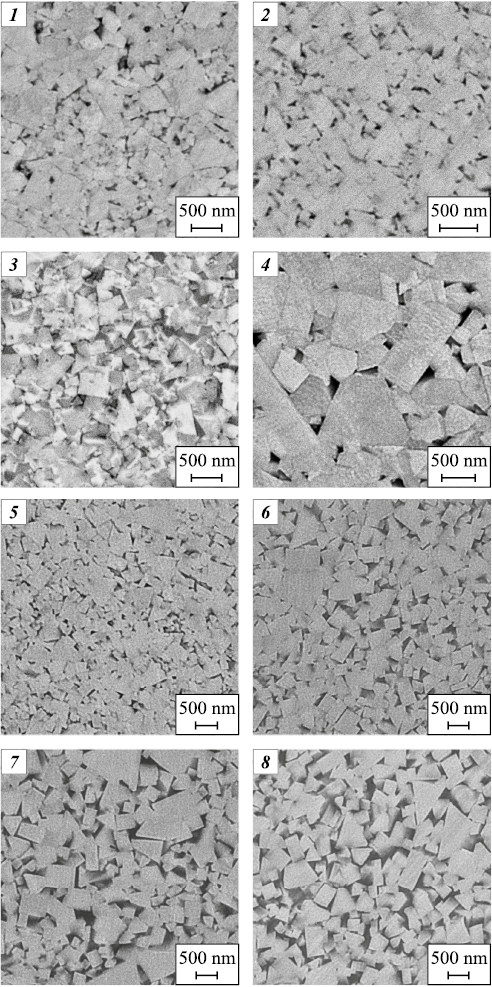

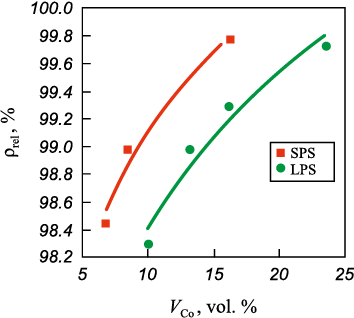

Fig. 2 presents the microstructures of materials fabricated using spark plasma sintering and liquid phase sintering. The density of the sintered cemented carbides (Fig. 2, samples 1–3) increases from 98.4 to 99.5 % as the cobalt content rises from 4 to 10 wt. %, which is attributed to the higher plasticity of cobalt (Fig. 3). Further increasing the density by raising the SPS temperature above 1200 °C is limited by the need to prevent grain growth and the extrusion of the cobalt phase from the samples. The use of a relatively low sintering temperature and the addition of grain growth inhibitors made it possible to limit the grain size to 0.17–0.19 µm (samples 1–3, Table 2). Therefore, all tungsten-cobalt cemented carbide samples sintered by SPS can be classified as nanostructured. In these samples, the grain faceting is not pronounced, since grain growth was insufficiently intensive.

Fig. 2. Microstructures of the samples fabricated using spark plasma sintering (1–4)

Fig. 3. Dependence of the relative density

Table 2. Characteristics of the sintered samples

|

The relative density of tungsten carbide produced by SPS reached 99.9 %, which is ensured by the high sintering temperature (2000 °C) and prolonged holding time (Table 2). The resulting WC is classified as an ultrafine-grained material, as its average grain size does not exceed 0.5 µm (see Fig. 2, sample 4), despite the presence of grain growth inhibitors.

The maximum temperature and holding time during LPS are limited only by grain growth. An increase in cobalt concentration from 6 to 15 % leads to a rise in the density of all fabricated samples (see Fig. 3, Table 2). During LPS, intense grain growth occurs through recrystallization via the liquid phase. As a result, the average WC grain size in samples 5–8 is significantly larger than that in the SPS-processed samples (Fig. 2, samples 1–4). The tungsten carbide grains in these alloys acquire a characteristic faceted shape.

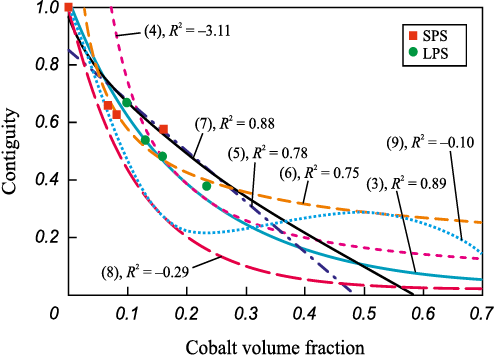

It can be expected that the contiguity values of materials obtained by SPS and LPS in vacuum will also deviate from existing empirical relationships [4; 7; 10; 11]. To describe contiguity, the authors of [21] proposed using exponential and power-law dependencies:

| \[C = 1.03{e^{ - 5{V_{{\rm{Co}}}}}},\] | (3) |

| \[C = 0.074V_{{\rm{Co}}}^{ - {\rm{1}}}.\] | (4) |

In [22], linear and power-law dependencies were presented:

| C = 0.85 – 1.8VCo , | (5) |

| \[C = 0.2V_{{\rm{Co}}}^{ - {\rm{0}}{\rm{.45}}}.\] | (6) |

The authors of [17] described the results of contiguity measurements using a scanning electron microscope, employing a power-law relationship:

| \[C = 1 - 1,43V_{{\rm{Co}}}^{0,63}.\] | (7) |

The authors of [23] proposed an additional exponential dependence and a quadratic function-based equation to describe contiguity in their experimental data [23]:

| \[C = {e^{ - 8.4{V_{{\rm{Co}}}}}},\] | (8) |

| \[C \cong 1 - \frac{{{V_{{\rm{Co}}}}}}{{\left( {{\rm{1}} - {V_{{\rm{Co}}}}} \right)\left( {5.975V_{{\rm{Co}}}^{\rm{2}} - 0.691{V_{{\rm{Co}}}} + 0.214} \right)}}.\] | (9) |

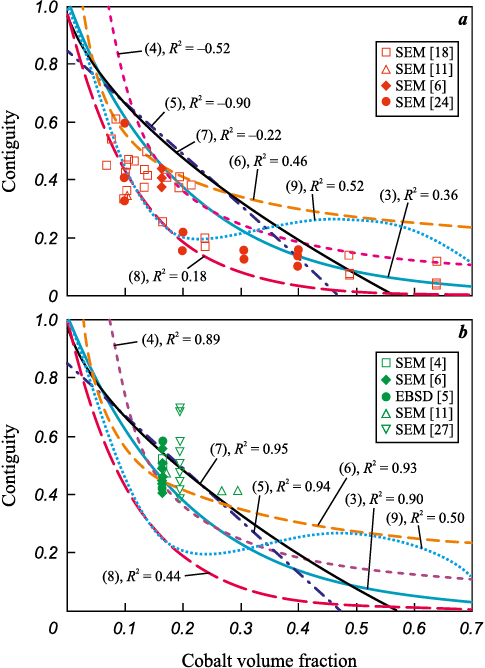

Fig. 4 presents the experimental contiguity values of the obtained materials alongside the theoretical relationships (3)–(9). For each equation, the coefficient of determination was calculated to assess the deviation of the experimental data from the theoretical predictions. It can be observed that the relationships (3), (5), (6), and (7) provide the best fit, with determination coefficients in the range of 0.75–0.89, which is significantly higher than the threshold value (0.5), and are superior to the remaining equations (4), (8), and (9). This may be attributed to the fact that the contiguity of WC grains in UFG and NS cemented carbides is higher than in conventional cemented carbides. A possible reason for this is that cobalt atoms are not always able to completely fill the intergranular space between WC grains when the intergranular distance approaches the lattice parameter of cobalt (≈0.4 nm). In such cases, the length of WC/WC contacts increases, while the length of the WC/Co phase boundary decreases. It is important to note that the limited resolution of scanning electron microscopes makes it difficult to observe such microstructural features.

Fig. 4. Dependence of the experimental contiguity values on the cobalt volume fraction in the microstructure of ultrafine-grained cemented carbide fabricated using SPS and LPS in this study |

To confirm this effect, an additional analysis was performed to assess the applicability of these relationships (Figs. 4 and 5) for describing the microstructures of ultrafine-grained cemented carbides compared to conventional cemented carbides based on literature data [4; 5; 11; 18; 23–26]. It should be noted that all contiguity measurements in the cited studies were performed using images obtained by conventional scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The use of electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) enables the identification of a greater number of WC/WC grain boundaries, thus providing a more accurate assessment of contiguity [6; 19–23; 25–28]. However, applying this method to UFG and NS tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides is challenging due to its limited resolution. Moreover, the existing relationships between hardness, strength, contiguity, and other microstructural parameters have been established based on SEM-derived data. Consequently, contiguity values obtained via EBSD are not applicable to these models.

Fig. 5. Dependence of the experimental contiguity values |

From Fig. 5, a, it can be seen that only dependence (9) satisfactorily describes (R2 = 0.52 > 0.50) the contiguity of conventional tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides, based on a sufficiently large dataset (87 values) from 10 different studies. Dependence (9) is positioned lower than relationships (3), (5), (6), and (7), which describe ultrafine-grained and nanostructured cemented carbides. Fig. 5, b presents contiguity values for UFG and NS cemented carbides, extracted from the same literature sources. It is evident that the dataset is incomplete due to the uneven representation of different cobalt concentrations, making it impossible to reliably assess the applicability of these dependencies for describing the contiguity of UFG and NS tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides. However, from Fig. 5, b, it follows that the contiguity values of UFG and NS cemented carbides fall in the upper range, close to dependencies (3)–(7) and far from (8)–(9), which are positioned lower. This suggests that the literature data also confirm that the contiguity of UFG and NS cemented carbides is higher than that of conventional cemented carbides.

All existing models describing the hardness of cemented carbides are based on the theory of mutual dislocation motion blocking in the cobalt matrix and the carbide skeleton [11; 18; 29]. The influence of microdefects on the hardness of cemented carbides has not been sufficiently studied [11]. The most widely accepted and commonly used model for describing the hardness of conventional cemented carbides is the one proposed by [18–20], which serves as the null hypothesis for all researchers developing new models [30–33]. This model is based on the rule of mixtures and the hypothesis of mutual dislocation motion blocking in the carbide framework and cobalt layers:

| HV = HVWC VWCC + HVCo (1 – VWCC). | (10) |

The hardness of the carbide framework (HVWC ) and cobalt layers (HVCo ) is determined using the Hall–Petch law [11; 18; 29]:

| \[H{V_{{\rm{WC}}}} = 1382 + \frac{{23,1}}{{\sqrt {d/1000} }},\] | (11) |

| \[H{V_{{\rm{Co}}}} = 304 + \frac{{12,7}}{{\sqrt {\lambda /1000} }}.\] | (12) |

where d is the average WC grain size, µm; λ is the mean free path in cobalt, µm.

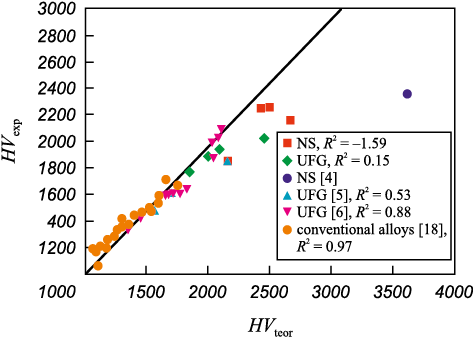

Fig. 6 shows that the experimental hardness values of all samples are lower than the theoretical estimates calculated using equations (10)–(12) based on microstructural parameters (see Table 2). This discrepancy is likely related to deviations in the hardness of the alloy constituents (WC and Co) from the values predicted by the Hall–Petch relationships (11) and (12). The most significant deviation is observed in nanostructured alloys 1–3. The hardness values of ultrafine-grained cemented carbides reported by other researchers [5; 6], the highest of which does not exceed 2100 HV, are satisfactorily described by the relationship (10) (R2 = 0.53 and 0.88). However, the hardness of the nanostructured alloy (2356 HV) reported in [4] was found to be 50 % lower than the calculated value (3517 HV). The deviations of experimental hardness values from theoretical predictions in nanostructured cemented carbides, as confirmed in this study, are likely due to the activation of non-dislocation deformation mechanisms.

Fig. 6. Comparison of experimental and theoretical hardness values |

Due to their smaller grain size, all samples (Fig. 6) exhibited significantly higher hardness values (HV = 1770÷2260), compared to conventional cemented carbides (HV = 1063÷1630). As a result, such tool materials are expected to demonstrate superior operational performance, including wear resistance and machining precision. The hardness of samples 5–8, produced via liquid phase sintering, was lower than that of the SPS-sintered samples (samples 1–4). This can be attributed to their higher cobalt content and larger average WC grain size. Due to its small carbide grain size (0.17 µm) and high WC content, nanostructured cemented carbide sample 2 (WC–5Co–0.4VC–0.4Cr3C2 ) exhibited the highest hardness (HV = 2260 ± 30). The SPS-sintered tungsten carbide, with a larger average grain size (0.5 µm), demonstrated slightly lower hardness (HV = 2250 ± 20).

Conclusions

Nanostructured tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides with an average grain size of d ~ 0.2 µm can be fabricated via spark plasma sintering of nanopowders with grain growth inhibitors at 1200 °C. Increasing the cobalt volume fraction from 6.8 wt. % to 16.3 wt. % leads to an increase in the relative density of sintered nanostructured cemented carbides from 98.4 to 99.5 % while having little effect on the WC grain size. Using liquid phase sintering at 1450 °C for 1 h, alloys with a density ranging from 98.3 to 99.9 % and d = 0.24–0.28 µm can be obtained from powders containing 6–15 wt. % Co. An increase in cobalt concentration results in higher density (due to an increased pore-filling rate) and larger grain size due to recrystallization via the liquid phase. Spark plasma sintering of nanopowdered tungsten carbide at 2000 °C enables the fabrication of an ultrafine-grained ceramic material with an average grain size of 0.5 µm and a maximum relative density of 99.9 %.

Measuring contiguity in nanostructured tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides is challenging due to their small grain size. The dependence of contiguity in sintered nanostructured and ultrafine-grained cemented carbides on the cobalt volume fraction was best described by a known exponential relationship C = 1.03exp(–5VCo ). Analysis of literature data has shown that many previously developed contiguity dependencies for conventional medium-grained, fine-grained, and submicron-grained cemented carbides are not applicable for describing nanostructured and ultrafine-grained materials, as their predicted values underestimate the experimental data.

The tungsten-cobalt cemented carbides obtained in this study exhibited significantly higher hardness than conventional medium-grained, fine-grained, and submicron-grained cemented carbides, primarily due to their smaller WC grain size. However, the experimental hardness values of the sintered cemented carbides were lower than theoretical predictions based on the Gurland and Lee model [18], which is derived from the Hall–Petch relationship. This discrepancy is likely due to the activation of non-dislocation deformation mechanisms. Due to its small WC grain size and high tungsten carbide content, sample 2 (WC–5Co–0.4VC–0.4Cr3C2) with an average WC grain size of 0.17 µm exhibited the highest hardness (HV = 2260 ± 30). The SPS-sintered tungsten carbide, with a larger WC grain size of 0.5 µm, exhibited a comparable hardness (HV = 2250 ± 20).

References

1. Dvornik M.I., Zaitsev A.V. Сhange in strength, hardness and cracking resistance in transition from medium-grained to ultrafine hard alloy. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings. 2017;(2):39–46. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2017-2-39-46

2. Dvornik M.I., Zaitsev A.V. Variation in strength, hardness, and fracture toughness in transition from medium-grained to ultrafine hard alloy. Russian Journal of Non-Ferrous Metals. 2018;59(5):563–569. https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821218050024

3. Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A. Production of WC–15Co ultrafine-grained hard alloy from powder obtained by VK15 alloy waste spark erosion in water. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings. 2020;14(3):4–16. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2020-3-4-16

4. Peng Y., Wang H., Zhao C., Hu H., Liu X., Song X. Nanocrystalline WC–Co composite with ultrahigh hardness and toughness. Composites Part B: Engineering. 2020;197:108161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108161

5. Zhao S., Song X., Wei C., Zhang L., Liu X., Zhang J. Effects of WC particle size on densification and properties of spark plasma sintered WC–Co cermet. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2009;27(6):1014–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2009.07.017

6. Zhao S., Wei C. Quantitative relationships between microstructure parameters and mechanical properties of ultrafine cemented carbides. Acta Metallurgica Sinica. 2011;47(9):1188–1194.

7. Dvornik M., Mokritskiy B., Zaytsev A. Comparative analysis of microabrasive wear resistance of traditional hard alloys and submicron hard alloy WC–8Co–1Cr3C2 . Voprosy materialovedeniya. 2015;(1):45–51. (In Russ.).

8. Fedorov D.V., Semenov O.V., Rumyantsev V.I., Ordanyan S.S. Peculiarities of compacting during sintering of VH8M alloy with addition of nanosized tungsten carbide. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings. 2014;(3):26–30. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2014-3-26-30

9. Wu Y., Lu Z., Qin Y., Bao Z., Luo L. Ultrafine/nano WC–Co cemented carbide: Overview of preparation and key technologies. Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2023;27:5822–5839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.10.315

10. Siwak P. Indentation induced mechanical behavior of spark plasma sintered WC–Co cemented carbides alloyed with Cr3C2 , TaC–NbC, TiC, and VC. Materials. 2021; 14(1):217–234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14010217

11. Jia K., Fischer T., Gallois B. Microstructure, hardness and toughness of nanostructured and conventional WC–Co composites. Nanostructured materials. 1998;10(5):875–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0965-9773(98)00123-8

12. Sun J., Zhao J., Huang Z., Yan K., Shen X., Xing J., Gao Y., Jian Y., Yang H., Li B. A review on binderless tungsten carbide: Development and application. Nano-Micro Letters. 2020;12(1):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0346-1

13. Kim H.-C., Shon I.-J., Garay J., Munir Z. Consolidation and properties of binderless sub-micron tungsten carbide by field-activated sintering. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2004;22(6):257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2004.08.003

14. Kim H.-C., Yoon J.-K., Doh J.-M., Ko I.-Y., Shon I.-J. Rapid sintering process and mechanical properties of binderless ultra fine tungsten carbide. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2006;435–436:717–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2006.07.127

15. Huang B., Chen L., Bai S. Bulk ultrafine binderless WC prepared by spark plasma sintering. Scripta Materialia. 2006;54(3):441–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCRIPTAMAT.2005.10.014

16. Dopita M., Salomon A., Chmelik D., Reichelt B., Rafaja D. Field assisted sintering technique compaction of ultrafine-grained binderless WC hard metals. Acta Physica Polonica A. 2012;122(3):639–642. http://dx.doi.org/10.12693/APhysPolA.122.639

17. Mingard K. P., Roebuck B. Interlaboratory measurements of contiguity in WC–Co hardmetals. Metals. 2019; 9(3):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/MET9030328

18. Lee H.-C., Gurland J. Hardness and deformation of cemented tungsten carbide. Materials science and engineering. 1978;33(1):125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5416(78)90163-5

19. Chermant J., Osterstock F. Elastic and plastic characteristics of WC–Co composite materials. Journal of Materials Science. 1976;11(3):106–109.

20. Gurland J. A structural approach to the yield strength of two-phase alloys with coarse microstructures. Materials Science and Engineering. 1979;40(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5416(79)90008-9

21. Exner H., Fischmeister H. Structure of sintered tungsten carbide-cobalt alloys. Archiv für das Eisenhüttenwesen. 1966;(37):409–415.

22. Roebuck B., Bennett E.G. Phase size distribution in WC/Co hardmetal. Metallography. 1986;19(1):27–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0800(86)90005-4

23. Luyckx S., Love A. The dependence of the contiguity of WC on Co content and its independence from WC grain size in WC–Co alloys. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2006;24(1-2):75–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2005.04.012

24. Nakamura M., Gurland J. The fracture toughness of WC–Co two-phase alloys – A preliminary model. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 1980;11(1):141–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02700449

25. Mingard K., Roebuck B., Bennett E., Gee M., Nordenstrom H., Sweetman G., Chan P. Comparison of EBSD and conventional methods of grain size measurement of hardmetals. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2009;27(2):213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJRMHM.2008.06.009

26. Tarrago J.M., Coureaux D., Torres Y., Wu F., Al-Dawery I., Llanes L. Implementation of an effective time-saving two-stage methodology for microstructural characterization of cemented carbides. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2016;55:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJRMHM.2015.10.006

27. Mandel K., Krüger L., Schimpf C. Study on parameter optimisation for field-assisted sintering of fully-dense, near-nano WC–12Co. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2014;45:153–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.04.009

28. Pellan M., Lay S., Missiaen J. M., Norgren S., Angseryd J., Coronel E., Persson T. Effect of binder composition on WC grain growth in cemented carbides. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2015;98(11):3596–3601. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.13748

29. Liu X., Zhang J., Hou C., Wang H., Song X., Nie Z. Mechanisms of WC plastic deformation in cemented carbide. Materials & Design. 2018;150:154–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2018.04.025

30. Xu Z.-H., Ågren J.A modified hardness model for WC–Co cemented carbides. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2004;386(1-2):262–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2004.07.061

31. Cha S.I., Lee K.H., Ryu H.J., Hong S.H. Analytical modeling to calculate the hardness of ultra-fine WC–Co cemented carbides. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 2008;489(1-2):234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2007.12.036

32. Makhele-Lekala L., Luyckx S., Nabarro F. Semi-empirical relationship between the hardness, grain size and mean free path of WC–Co. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2001;19(4-6):245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-4368(01)00022-1

33. Kresse T., Meinhard D., Bernthaler T., Schneider G. Hardness of WC–Co hard metals: Preparation, quantitative microstructure analysis, structure-property relationship and modeling. International Journal of Refractory Metals & Hard Materials. 2018;(75):287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2018.05.003

About the Authors

M. I. DvornikRussian Federation

Maksim I. Dvornik – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Senior Research Scientist, Head of the Powder Metallurgy Laboratories

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

E. A. Mikhailenko

Russian Federation

Elena A. Mikhailenko – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.) Senior Research Scientist of the Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

O. O. Shichalin

Russian Federation

Oleg O. Shichalin – Cand. Sci. (Chem.) Senior Research Scientist of the Institute of Science-Intensive Technologies and Advanced Materials

10 Ajax Bay, Russky Island Vladivostok 690922, Russia

I. Yu. Buravlev

Russian Federation

Igor Yu. Buravlev – Cand. Sci. (Chem.) Deputy Director for Development of the Institute of Science-Intensive Technologies and Advanced Materials

10 Ajax Bay, Russky Island Vladivostok 690922, Russia

A. A. Burkov

Russian Federation

Aleksandr A. Burkov – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher, Head of the Laboratory of Physical and Chemical Fundamentals of Material’s Technology

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

N. M. Vlasova

Russian Federation

Nuriya M. Vlasova – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Research Scientist of the Powder Metallurgy Laboratories

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

E. V. Chernyakov

Russian Federation

Evgeny V. Chernyakov – Laboratory Assistant of the Powder Metallurgy Laboratories

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

V. K. Khe

Russian Federation

Vladimir K. Khe – Junior Research Scientist of the Laboratories of Construction and Instrumental Materials

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

P. G. Chigrin

Russian Federation

Pavel G. Chigrin – Cand. Sci. (Chem.) Senior Research Scientist of the Laboratory of Physical and Chemical Fundamentals of Material’s Technology

153 Tikhookeanskaya Str., Khabarovsk 680042, Russia

Review

For citations:

Dvornik M.I., Mikhailenko E.A., Shichalin O.O., Buravlev I.Yu., Burkov A.A., Vlasova N.M., Chernyakov E.V., Khe V.K., Chigrin P.G. Grain contiguity of tungsten carbide and hardness of nanostructured and ultrafine-grained WC–(Co)–VC–Cr3C2cemented carbides fabricated by spark plasma and liquid phase sintering. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2025;19(2):51-61. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2025-2-51-61