Scroll to:

Multicriteria optimization of mechanical processing for Pb–C composite charge material

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2023-4-25-33

Abstract

This study investigates a two-stage processing approach for a charge of Pb–C composite powder material composed of lead (PS1) and graphite (GISM) powders in a high-energy mill under ambient air conditions. The study aims to determine the influence of graphite content (Cg ) and mechanical activation time (τ) on the particle size distribution of the charge. The results indicate that the particle size distribution can be effectively described using the Rosin–Rammler equation. Furthermore, a correlation between the equation's parameters and the quality of the resulting hot compacted materials, as well as an index derived from the generalized desirability function, has been identified. The study delves into the mechanism behind the formation of the Pb–C powder charge during mechanical activation, which involves the creation of loosely bound agglomerates of composite particles. These agglomerates can be easily disrupted during manual processing of the charge in a mortar. Notably, the research reveals that the extremum of the particle size distribution shifts towards smaller average sizes of the Pb–C composite particles that constitute the agglomerates. The size of these formed agglomerates is shown to depend on both the graphite content in the charge and the duration of mechanical processing. Using multicriteria optimization, the study identifies the optimal values for technological factors (τ = 1.8 ks, Cg = 0.15 wt. %) for charge preparation in the two-stage mechanical processing mode. These optimal values result in an enhanced set of physical and mechanical properties for the Pb–C hot-compacted composite material, including shear strength (σshear = 6.3 MPa), hardness (HRR = 109), and electrical conductivity (L = 1.812 Ω–1) of Pb–C. X-ray diffraction analysis conducted during the study reveals the formation of lead oxides during the mechanical activation of the Pb–C charge. Additionally, it indicates an increase in the half-width of the diffraction profile of lines (111) and (222), which subsequently decreases after the hot-compaction process. Comparative data involving the use of lead-based chip waste and lead powder-based composites are also presented in the study. These data suggest that a lower optimum graphite content is required for lead powder PS1 (Cg = 0.15 wt. %) compared to chip waste (Cg = 0.5 wt. %).

Keywords

For citations:

Vasiliev A.N., Sergeenko S.N. Multicriteria optimization of mechanical processing for Pb–C composite charge material. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2023;17(4):25-33. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2023-4-25-33

Introduction

When producing powder composite materials (CM) based on mechanically activated mixtures, sintering, and hot compaction technologies are employed. The mechanical properties of powder materials are dependent on the technological parameters of mechanical activation (MA) [1] of the charge in high-energy mills. Previous studies have established a relationship between the particle size distribution and the chemical composition of the charge, as well as the structure and properties of the powder material, and the results of cold compacting (CC) and hot compacting (HC) [2].

At Platov South-Russian State Polytechnic University (NPI), research has been conducted on the mechanical activation [1–3] of various powder mixtures in dry and liquid media (Fe–Al, Al–Si, Al–C, Fe–Mn, BrAZh, and D-16 shavings, as well as Pb shavings with the addition of graphite). During the MA of a powder charge, multi-stage processes of dispersion and agglomeration are observed, leading to the formation of composite particles with structural heredity. These processes affect the activation of compaction during sintering and the subsequent hot additional compaction of workpieces [1–4]. The kinetics of dispersion and agglomeration depend on the MA modes and the composition of the charge. The use of liquid media and the introduction of graphite prevent the formation of agglomerates due to the formation of an interparticle interface [3–7]. Preliminary studies [3] revealed that when graphite is introduced into the charge in excess of 0.5 wt. % and subsequent hot compaction of the material, cracks occur in the powder material.

For the production of electrodes for lead-acid batteries, lead-based CMs with the addition of graphite, as well as various carbon-containing additives (carbon nanotubes, fullerene black, graphene, activated carbon, etc.) are employed [8–20]. Pb–C composite material has also found applications in lithium-ion batteries [20]. The conducted studies have shown that the maximum amount of graphite in CM should not exceed 1 wt. % with an optimum content ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 wt. % [12; 14; 17; 18]. Graphite content above 1 wt. % leads to deterioration of the rheological properties of the active material paste. The introduction of graphite improves the electrical conductivity, mechanical properties, and chemical efficiency of the Pb–C composite material. Modifying the composition of CM with graphite, unlike other components, is characterized by a lower cost and increased safety [20].

The objective of this study is to perform multicriteria optimization of the graphite content in the charge and processing time, with the goal of achieving an improved set of physical and mechanical properties for hot-compacted Pb–C composite material.

Experimental

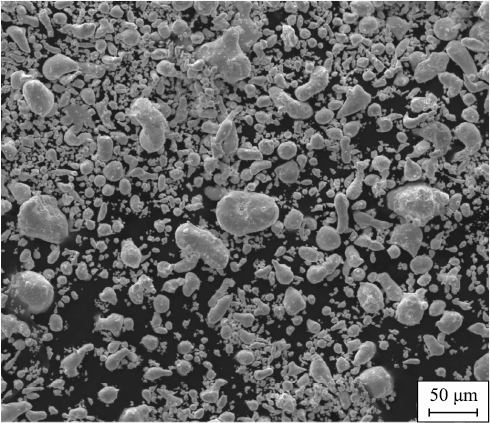

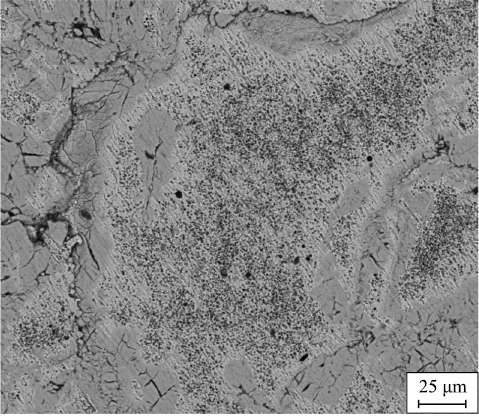

Lead powders PS1 (Specifications TU 48-6-123-91) (Fig. 1) and artificial special low-ash graphite (GISM, State Standard GOST 18191-78) were utilized as the initial materials. The two-stage technology for preparing the charge [1–4], carried out in a SAND-1 planetary ball mill (Armenia), involved mixing (τ = 1.2 ks, n = 150 s\(^-\)1) followed by subsequent mechanical activation (τ = 0.6÷3.6 ks, n = 290 s\(^-\)1). The design of experiments and the obtained results are presented in Table 1. The process layout for obtaining hot-compacted samples included preliminary cold compaction (500 MPa) of the charge, followed by heating in a furnace (Т = 473 K, τ = 0.3 ks) in an ambient air and dynamic hot compaction with extrusion elements (W = 36.6 MJ/m3) [4].

Fig. 1. SEM image of as delivered PS1 lead powder

Table 1. Design of experiments and results

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The particle size distribution of the activated charges (in accordance with State Standard GOST 18318-94) was determined both before and after manual processing in a mortar. This analysis was conducted using a sieve analyzer, model 029 (OOO Litmashpribor, Usman). Additionally, the hardness HRR (according to State Standard GOST 24622-91) of the hot-compacted composite powder material was studied using a TR 2140 device (OOO ASMA-Pribor, Svetlovodsk, Ukraine). The shear strength (δshear ) of the extruded element (dee = 3.1 mm) was determined using a UMM-5 universal machine (OOO “ASMA-Pribor”, Svetlovodsk, Ukraine). All measurements of physical, mechanical, and operational properties were carried out in comparison with a lead-based cast sample, which had a hardness of HRR = 60÷70. Electrical conductivity measurements were conducted in accordance with State Standards GOST 24606.3-82 and 4668-75 (U = 50 mV, I = 10 mА) using equipment developed at YuRGPU (NPI) [21], with a load of 30 ± 1 N.

To describe the particle size distribution of charge, the Rosin-Rammler function reduced to linear form was employed [1; 22], allowing for the determination of parameters α and β as follows:

| y = a + bx, | (1) |

where y = ln (ln В\(^-\)1); a = ln α; b = β; x = ln X; B represents the content of sieved Pb–C charge, wt. %; X stands for the particle size.

Additional grinding in a mortar was carried out to assess the degree of agglomeration of charge particles during the MA. This is characterized by the agglomeration index (AGI) [23], calculated as the ratio of the average particle sizes of the activated (d0 ) and mortar-processed (d1 ) charge:

| AGI = d0 /d1 . | (2) |

The morphology and spectral analysis of Pb–C charge particles were investigated using a “Quanta 200” scanning electron microscope (FEI Company, USA) at the Nanotechnologies Resource Sharing Center of Southern Russian State Pedagogical University (NPI). Additionally, thermogravimetric analysis in a helium atmosphere was conducted using an STA 449C synchronous thermal analyzer (NETZSCH, Germany).

Table 1 summarizes the following parameters: Сg represents the graphite content in the charge, wt. %; τ is the time of mechanical activation, ks; d0 indicates the average particle size of the charge after activation, μm; d1 signifies the average particle size of the blend after manual processing in a mortar, μm; α0 , β0 and α1 , β1 denote the parameters of the Rosin–Rammler equation for the charge, respectively, after mechanical activation and manual processing in a mortar; \(r_0^2\), \(r_1^2\) represent the determination coefficients of the Rosin–Rammler equation for the charge after mechanical activation and subsequent manual processing in a mortar, respectively.

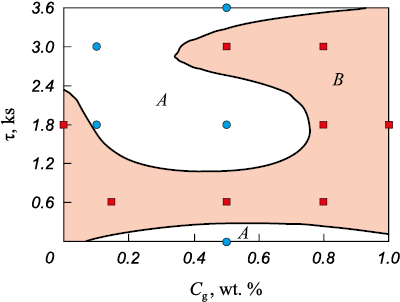

As shown in Figure 2, a range of technological parameters has been identified that ensures the production of Pb–C composite powder material without visible cracks and with cracks on the edge surface of a sample.

Fig. 2. Ranges of technological parameters ensuring |

Specifically, avoiding cracks is achieved by increasing the MA time of the charge to more than 1.8 ks and maintaining the graphite content in the charge at less than 0.5 wt. %. This combination of parameters results in the formation of hot-compacted material with a smooth surface, both on the sides and edges. Additionally, achieving a similar outcome is possible with Cg = 0.5 wt. % and in the absence of MA (τ = 0 ks), i.e., when the mixture is obtained solely through agitation.

At high graphite contents, there is an observable increase in non-metallic inclusions, which in turn reduces the plasticity of the material. Increasing the duration of MA leads to a more uniform distribution of graphite throughout the entire bulk of the charge and eliminates the occurrence of cracks during deformation of the material.

Result and discussion

An analysis of the influence of graphite content in the charge and the duration of mechanical activation has shown that as τ increases, the average particle size of the activated charge (d0 ) increases across all studied Сg . Manual processing in a mortar results in the crushing of agglomerates, leading to agglomeration index values (AGI) greater than 1. In this case, the maximum values of d0 are observed after processing in a planetary mill when both Сg and τare increased. When the graphite content in the charge is increased to 0.5 wt. % and the treatment duration is extended to 1.8 ks, the dimensions of d0 stabilize (refer to Table 1). Manual processing contributes to the breakdown of agglomerates across the entire range of studied Сg and τ. Larger average particle sizes, constituting the agglomerates (d1 ), are observed when the graphite content in the charge is 0.15 wt. %.

The addition of a higher graphite content (1 wt. %) into the charge results in an increased agglomeration index AGI, defined as the ratio of d0 to d1 [1; 2]. When the graphite content in the charge is 0.5 wt. %, and the MA duration is 1.8 ks, it results in the formation of particularly resistant agglomerates (d0 ≈ d1 , AGI = 1.16).

An increase in τ to 1.8 ks results an elevated coefficient of determination \(r_0^2\) of the Rosin–Rammler equation when reduced to linear form (1). In this instance, the calculated parameter α0 decreases. The function α0 (τ) exhibits an extreme behavior. Following manual processing in a mortar and an extended MA time, there is an observed increase in β1 .

Multicriteria optimization of process variables

In pursuit of multicriterial optimization (MCO) for the technological factors governing mechanical activation (Сg , τ), with the goal of enhancing a comprehensive set of physical and mechanical properties (ultimate shear strength σshear , hardness HRR, electrical conductivity L, and porosity P) of the Pb–C composite material, a generalized desirability function D was determined [3; 24]. This function employs the following scale: D = 0.75÷1.0 indicating an excellent level of quality; 0.68÷0.74 representing high quality; 0.6÷0.67 signifying acceptable quality; 0.5÷0.59 denoting sufficient quality; and less than 0.5 reflecting an unacceptable level.

The results of the MCO values for Cg and τ, ensuring the production of high-quality Pb–C composite material, are presented in Table 2, ordered in descending order of D values. Analysis of the MCO results has revealed that an excellent level of quality (D = 0.81) is achieved with a graphite content in the charge of 0.15 wt. % and a processing time of 1.8 ks. The experimental results and the optimized MA parameters pertain solely to the studied range of graphite contents and processing times in a SAND-1 planetary ball mill.

Table 2. Results of multicriteria optimization of technological factors

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

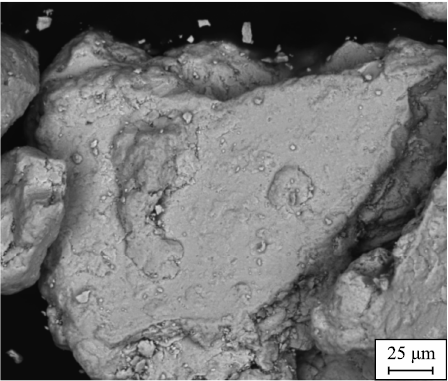

In order to determine the optimal composition of the composite material (refer to Table 2), X-ray phase analysis of the mechanically activated mixture was conducted, and the morphology of its particles was investigated (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. SEM image of the charge after mechanical activation |

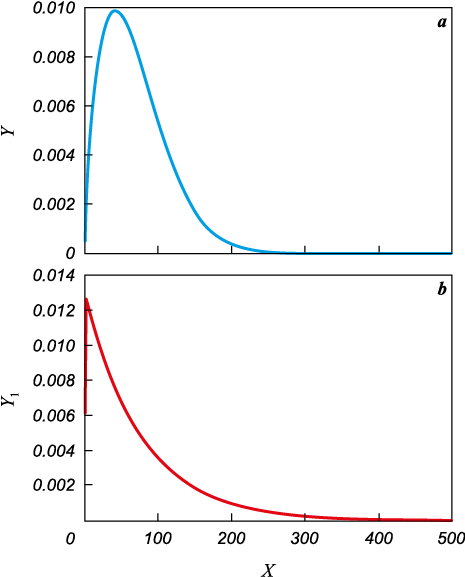

Experimental findings have confirmed the formation of agglomerates during the process of MA in a high-energy mill. These agglomerates are subsequently broken down during grinding in a mortar (Fig. 4). During manual processing in a mortar, a noticeable shift occurs in the extremum of the particle size distribution function toward smaller average sizes of Pb–C composite particles.

Fig. 4. Particle size distribution, plotted according to the Rosin-Rammler equation, |

Reducing the charge processing time from 3.0 to 1.8 ks results in a decrease in the intensity of the PbO lines due to a lower degree of oxidation of the powder material (Fig. 5). Increasing the graphite content to 0.5 wt. % with a short processing time (τ = 1.8 ks) enables a reduction in material oxidation during MA.

Fig. 5. Diffraction patterns of lead powder in the as-delivered state (а) |

Analysis of the diffraction pattern revealed that particles within the mechanically activated Pb–C charge contain PbO (Fig. 5). Mechanical activation of the powder charge results in the broadening of the profile of the lines (111) and (222) of lead due to an increase in microstresses and a reduction in the size of the mosaic blocks. Subsequent operations involving short-term heating and HC cause a decrease in the half-width of the diffraction profile of the lines (Table 3).

Table 3. Calculated half-widths of the diffraction profile of Pb lines

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When substituting lead chips and GK-3 graphite used in [3] with PS-1 and GISM lead powder, the optimal graphite content decreases from 0.5 to 0.15 wt. % at a processing time of 1.8 ks in a high-energy mill.

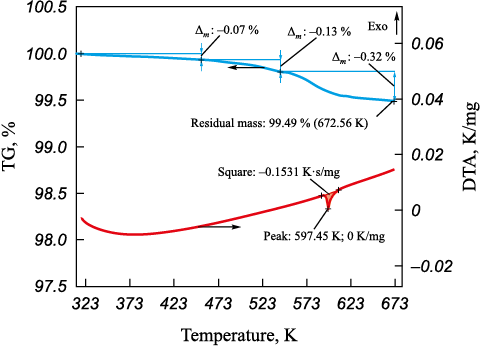

Figure 6 illustrates the microstructure of the hot-compacted composite powder material (T = 473 K, τ = 0.3 ks, medium: air, W = 36.6 MJ/m3) based on Pb–C charge (Cg = 0.15 wt. %) processed in a high-energy mill (τ = 1.8 ks), resulting in improved physical and mechanical properties, including hardness, strength, electrical conductivity, and porosity. The Pb–C charge (0.15 wt. %) that facilitates the production of hot-compacted material with increased hardness and electrical conductivity is characterized by extreme parameters of the Rosin–Rammler equation (α0 = α0min = 0.001; β0 = β0max = 1.59). Concurrently, the agglomeration index AGI = 1.16 indicates the formation of intractable agglomerates (d0 ≈ d1 ). Additionally, thermal analysis of the charge material revealed a shift (from 598 to 543 K) in the peak of the melting onset curve of the material compared to PS1 powder in its initial state due to the accumulation of material energy during the mechanical activation process (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. SEM image of hot-compacted composite powder material

Fig. 7. Thermogravimetric analysis of hot-compacted Pb–C |

Conclusions

The results of the studies have revealed several important findings. Increasing the duration of mechanical activation to optimal values (τ = 1.8 ks) leads to a higher degree of compliance of the charge’s particle size distribution with the Rosin–Rammler equation. The optimal parameters for mechanical activation of the charge (τ ~ 1.8 ks, Cg = 0.15 wt. %), which correspond to the extreme parameters of the Rosin–Rammler equation (α0 = α0min = 0,001; β0 = β0max = 1,59), result in improved values of the generalized desirability functions for the hot-compacted composite powder material (CPM).

Experimental evidence demonstrates that during mechanical processing in a high-energy mill, agglomerates are formed, but these agglomerates are subsequently broken down during manual processing in a mortar. In this scenario, the extremum of the particle size distribution function shifts toward smaller average sizes of the Pb–C composite particles that constitute the agglomerates.

When using the optimal values of technological factors (τ = 1.8 ks, Cg = 0.15 wt. %), the structure of hot-compacted Pb–C CPMs is formed, leading to improved consolidation quality of the composite material. This is characterized by the absence of identifiable interfaces on the interparticle splice surfaces and enhanced mechanical properties (HRR = 109, σshear = 6.3 MPa) and electrical conductivity (L = 1.812 Ω\(^-\)1).

References

1. Slabkii D.V., Sergeenko S.N., Popov Yu.V., Saliev A.N. X-ray diffraction analysis of powder materials based on mechanochemically activated D-16 chips with the addition of nickel powder. Tekhnologii obrabotki materialov. 2021;19(3):61–67. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.18503/1995-2732-2021-19-3-61-67

2. Sergeenko S.N. Kinetics of dispersion-agglomeration processes during mechanical activation of the charge of 110G13 powder steel. Chernye Metally. 2019;(7):47–52. (In Russ.).

3. Sergeenko S.N., Vasiliev A.N., Yatsenko A.N., Marakhovskii M.A. Multicriteria optimization of obtaining hot-compacted Pb–C composite materials based on shavings from recycled battery electrodes. Tsvetnye Metally. 2020;(11):63–69. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17580/tsm.2020.11.09

4. Streletskii A.N., Kolbanev I.V., Borunova A.B., Leonov A.V., Nishchak O.Yu., Permenov D.G., Ivanova O.P. Mechanochemical preparation of highly dispersed MeO/C composites as materials for supercapacitors and ion batteries. Colloid Journal. 2021;(83):763–773. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1061933X21060132

5. Kostikov V.I., Dorofeev Yu.G., Eremeeva Zh.V., Zherditskaya N.N., Ulyanovskii A.P., Sharipzyanova G.Kh. Features of the use of non-traditional carbon-containing components in the technology of powder steels. Message 2. Influence of non-traditional carbon-containing components on sintering processes in powder steel technology. Izvestiya Vuzov. Powder Metallurgy and Functional Coatings. 2008;(4):5–8. (In Russ.).

6. Shial S.R., Masanta M., Chairab D. Recycling of waste Ti machining chips by planetary milling: Generation of Ti powder and development of in situ TiC reinforced Ti–TiC composite powder mixture. Powder Technology. 2018;(15):232–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2018.01.080

7. Xiaopeng H., Ying H., Suhua Z., Xu S., Xuanyi P., Xuefang C. Effects of graphene content on thermal and mechanical properties of chromium-coated graphite flakes/Si/Al composites. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics. 2018;(29):4179–4189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-017-8363-7

8. Jian Gu, Jing Zhong, Kai-da Zhu, Xin-ru Wang, Sen-lin Wang. In-situ synthesis of novel nanostructured Pb–C composites for improving the performance of lead-acid batteries under high-rate partial-state-of-charge operation. Journal of Energy Storage. 2021;(33):102082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.102082

9. Zhang W., Lin H., Lu H., Liu D., Yin J., Lin Z. On the electrochemical origin of the enhanced charge acceptance of the lead-carbon electrode. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2015;(3):4399–4404. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA05891G

10. Cheng F., Liang J., Tao Z., Chen J. Functional materials for rechargeable batteries. Advanced Materials. 2011;(23): 1695–1715. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201003587

11. Marom R., Ziv B., Anerjee A., Cahana B., Luski S., Aurbach D. Enhanced performance of starter lighting ignition type lead-acid batteries with carbon nanotubes as an additive to the active mass. Journal of Power Sources. 2015;(296):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.07.007

12. Pavlov D., Nikolov P., Rogachev T. Influence of carbons on the structure of the negative active material of lead-acid batteries and on battery performance. Journal of Power Sources. 2011;(196):5155–5167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.02.014

13. Fernández M., Valenciano J., Trinidad F., Muñoz N. The use of activated carbon and graphite for the development of lead-acid batteries for hybrid vehicle applications. Journal of Power Sources. 2010;(195):4458–4469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.12.131

14. Zou X., Kang Z., Shu D., Liao Y., Gong Y., He C., Hao J., Zhong Y. Effects of carbon additives on the performance of negative electrode of lead-carbon battery. Electrochimica Acta. 2014;(151):89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2014.11.027

15. Kumar S.M., Ambalavanan S., Mayavan S. Effect of graphene and carbon nanotubes on the negative active materials of lead acid batteries operating under high-rate partial-state-of-charge operation. RSC Advances. 2014;(4): 36517. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA06920J

16. Zhao L., Zhou W., Shao Y., Wang D. Hydrogen evolution behavior of electrochemically active carbon modified with indium and its effects on the cycle performance of valve-regulated lead-acid batteries. RSC Advances. 2014;(4): 44152–44157. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA04670F

17. Long Q., Ma G., Xu Q., Ma C., Nan J., Li A., Chen H. Improving the cycle life of lead-acid batteries using three-dimensional reduced graphene oxide under the high-rate partial-state-of-charge condition. Journal of Power Sources. 2017;(343):188–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.01.056

18. Swogger S.W., Everill P., Dubey D.P., Sugumaran N. Discrete carbon nanotubes increase lead acid battery charge acceptance and performance. Journal of Power Sources. 2014;(261):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.03.049

19. Sugumaran N., Everill P., Swogger S.W., Dubey D.P. Lead acid battery performance and cycle life increased through addition of discrete carbon nanotubes to both electrodes. Journal of Power Sources. 2015;(279):281–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.12.117

20. Li Q., Xu C., Yang L., Pei K., Zhao Y., Liu X., Che R. Pb/C Composite with spherical Pb nanoparticles encapsulated in carbon microspheres as a high-performance anode for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Applied Energy Materials. 2020;(3):7416–7426. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.0c00812

21. Dorofeev Yu.G., Naumenko A.A., Radikainen L.M., Gritsenko S.I., Sergeenko S.N. Measurement of electrical resistivity of sintered products. Zavodskaya Laboratoriya (Diagnostika Materialov). 1995;(8):41–43. (In Russ.).

22. Khodakov G.S. Physics of grinding. Moscow.: Nauka, 1972. 307 р. (In Russ.).

23. Dyuzhechkin M.K., Sergeenko S.N., Popov Y.V. Features of structure and property formation for hot-deformed materials of the Al–Si and Al–Si–C systems based on mechanochemically activated charges. Metallurg. 2015;(9):86–91. (In Russ.).

24. Novik F.S. Optimization of metal technology processes by methods of planning experiments. Moscow: Mashinostroenie, 1980. 304 р. (In Russ.).

About the Authors

A. N. VasilievRussian Federation

Aleksandr N. Vasiliev – Postgraduate Student of the Department of Engineering Technology, Technological Machines and Equipment

132 Prosveshcheniya Str., Novocherkassk, Rostov Region 346428, Russia

S. N. Sergeenko

Russian Federation

Sergey N. Sergeenko – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Prof. of the Department of Engineering Technology, Technological Machines and Equipment

132 Prosveshcheniya Str., Novocherkassk, Rostov Region 346428, Russia

Review

For citations:

Vasiliev A.N., Sergeenko S.N. Multicriteria optimization of mechanical processing for Pb–C composite charge material. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2023;17(4):25-33. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2023-4-25-33