Scroll to:

Plasma-chemical synthesis of highly dispersed core–shell structures from a mechanical mixture of titanium carbide and titanium nickelide

https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-3-5-15

Abstract

In this paper, we studied the formation of ultrafine and nanocrystalline core–shell structures based on refractory compounds of titanium with nickel during plasma-chemical synthesis of a mechanical mixture of TiC and TiNi in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma. Cooling took place in an intensely swirling nitrogen flow in a quenching chamber. The derived products were separated in a vortex-type cyclone and a bag-type fabric filter. After processing, the products were subjected to encapsulation aimed at reducing the pyrophoricity for long-term storage of the resulting finely dispersed powders under normal conditions. X-ray diffraction and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy were used to study the resulting powder products of plasma-chemical synthesis, and density measurements were conducted. Additionally, to define the average particle size more accurately, the specific surface was measured using the BET method. The instrumental research revealed the presence of ultra- and nanodispersed particles with a core–shell structure in the powder products. These particles included titanium carbide-nitride compounds as a refractory core and metallic nickel as a metallic shell. In addition, the presence of complex titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N was recorded. According to direct measurements, the average particle size of the nanocrystalline fraction is 18.9 ± 0.2 nm. The obtained research results enabled us to develop a chemical model of crystallization of TiCxNy–Ni core–shell structures, which is implemented in a hardening chamber at a crystallization rate of 105 °С/s. To fabricate the model, we used the reference data on the boiling and crystallization temperatures of the elements and compounds being a part of highly dispersed compositions and recorded by X-ray diffraction, as well as the ΔG(t) dependences for TiC and TiN.

Keywords

For citations:

Avdeeva Yu.A., Luzhkova I.V., Murzakaev A.M., Ermakov A.N. Plasma-chemical synthesis of highly dispersed core–shell structures from a mechanical mixture of titanium carbide and titanium nickelide. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2024;18(3):5-15. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-3-5-15

Introduction

At present, the nanocrystalline state of matter is extensively investigated [1–5] as it has a number of unique physicochemical and physicomechanical properties determined by the high dispersion of particles. For example, the most productive methods for the formation of nanocrystalline materials include plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature gas plasma [6]. From the standpoint of fundamental research [7], “quasi-equilibrium” processes occurring during plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature gas plasma enable one to use the laws of equilibrium thermodynamics to calculate the final state of the reacting system.

The formation of core–shell structures of a given composition during synthesis of ultra- and nanodisperse materials based on refractory compounds of IV–VIA subgroups of the periodic table, with the participation of metals such as Ni and Co, makes it possible to synthesize composite powder products suitable for direct use. One of the technological examples is the use of nanomaterials, obtained during plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma and based on refractory compounds of titanium, vanadium, zirconium and other elements of IV–VIA subgroups, as modifiers for casting steels and non-ferrous alloys, as described in [8–10]. During extra-furnace steel processing, nanocrystalline materials are placed into a ladle using different methods and are rather evenly distributed throughout the molten steel or non-ferrous alloy, acting as artificial nuclei during crystallization. The metal components of composite nanocrystalline particles, therefore, serve as a buffer layer between the melt and the refractory core, protecting the latter from early solid-phase dissolution. The microquantities of such modifiers improve the physical and mechanical properties of cast materials while maintaining their specified chemical composition.

On the other hand, refractory compounds based on elements of IV–VIA subgroups of the periodic table, with high hardness values, are used as the basis for tool materials [11]. The binding phases are metals and their intermetallic compounds, which allow metal ceramic compositions to be formed, where the matrix in the form of grains of refractory compounds is impregnated with a metal melt during high-temperature sintering in vacuum with the participation of a liquid phase. The patterns of such processes for various powder compositions based on titanium carbonitride TiC0.5N0.5 were earlier described in [12–16].

The main objective of this paper is to study the patterns for the formation of ultradisperse and nanocrystalline particles with a core–shell structure during plasma-chemical synthesis of a mechanical mixture of TiC and TiNi (1:1) in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma.

Methods

Microcrystalline powders of titanium carbide (50 μm) and titanium nickelide (40 μm) were used as the initial components of the charge for plasma-chemical synthesis. The industrial plasma-chemical plant described in[6] was used for plasma-chemical synthesis. The plant productivity can reach 1 t/h, which confirms a quite reasonable cost of this technology.

The capacity of the plasma chemical plant (FSUE SRIOCCT, Saratov) was 25 kW, voltage – 200–220 V, current – 100–110 A, plasma flow speed – 55 m/s, gaseous nitrogen flow rate in the plasma reactor – 25–30 m3/h (of which plasma formation accounted for 6 m3/h and stabilization and hardening – 19–24 m3/h). The initial mechanical mixture consumption was 200 g/h.

The pneumatic transport transferred the processed ultrafine and nanocrystalline powder into a vortex-type cyclone and a bag-type fabric filter for separation. Nitrogen was used as a transport gas. After cooling, air was slowly introduced into the separation units to form a thin passivating oxide film. At the next passivation stage, the materials were encapsulated in a specialized unit of a plasma-chemical plant (capsulator), which ensures long-term storage of highly dispersed materials under normal conditions. The technique of plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma based on the plasma recondensation scheme is described in more detail in [6].

The core–shell structures processed in the form of ultrafine and nanocrystalline powders were studied by X-ray diffraction (SHIMADZU XRD 7000 X-ray diffractometer, CuKα-cathode, Japan) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR TEM) (JEOL JEM 2100 transmission electron microscope, Japan). The X-ray investigation results were processed using the WinXPOW software (ICDD database) to determine the phase composition of the resulting core–shell structures. The crystallographic parameters of the phase components were specified in the PowderCell 2.3 software package using the ICSD file located on the Springer Materials e-platform. The electron microscope images were processed to measure particle sizes in Measurer software and then in standard mathematical editors to construct distribution histograms and determine the average particle size. High-resolution images were processed in the DigitalMicrograph 7.0 software. The results of interplanar spacing measurements were compared with the ICDD database file to specify the phase composition and determine the local states of additionally detected phases.

The density of the final synthesis products was assessed using a helium pycnometer (AccuPyc II 1340 V1.09, Micromeritics, USA). The specific surface area was measured on a specific surface area analyzer (Gemini VII 2390 V1.03 (V1.03 t), USA) using the BET method. The average particle size was determined for each of the processed fractions based on the values of density and specific surface area [17].

Results and discussion

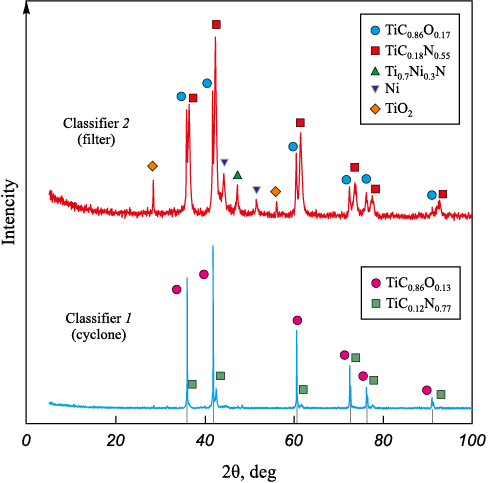

The results of X-ray investigations of fractions of core-shell structures obtained during plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma of a mechanical mixture of TiC and TiNi are presented in Fig. 1 and in the table. The refractory phase in both fractions of dispersed materials is represented by cubic compounds.

Fig. 1. X-ray diffraction patterns of highly dispersed fractions obtained from a mechanical mixture

Phase composition, density (ρ), specific surface area (Ssp) and the calculated value

|

While specifying the unit cell parameters, we revealed that during crystallization in a quenching chamber at a rate of 105 °C/s, oxycarbide and carbonitride phases of various compositions are formed in each fraction, as indicated in the table. The carbonitride composition is formed with a predominant amount of nitrogen in the non-metallic sublattice.

According to X-ray diffraction results, the cubic Ni phase (Fm-3m space group) is observed only in the fabric filter fraction, where its amount is determined to be 5 wt. % (see the Table). At the same time, the X-ray diffraction pattern of the powder composition from the filter contains complex titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N in the amount of 5 wt. %. According to the X-ray diffraction patterns (see Fig. 1), titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N, the visualization of which was presented in [18], is in a highly deformed state causing changes in intensities [19]. The resulting preferential orientation of the crystal lattice, in accordance with [20], can be ensured by the high rate of crystallization of the obtained powders. The issues related to formation and identification of Ti0.7Ni0.3N using the example of the TiN–Ni core–shell structure, studied within the framework of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, are discussed in [21]. The rutile modification of TiO2 is formed in the course of forced acidification by slow inflow of air into classifiers 1 and 2, its share being 2 wt. %.

The measurements of pycnometric density and specific surface area by the BET method, presented in the table, revealed that the core–shell structures formed differ in density values. This effect can be attributed to the quantitative content of the processed compositions.

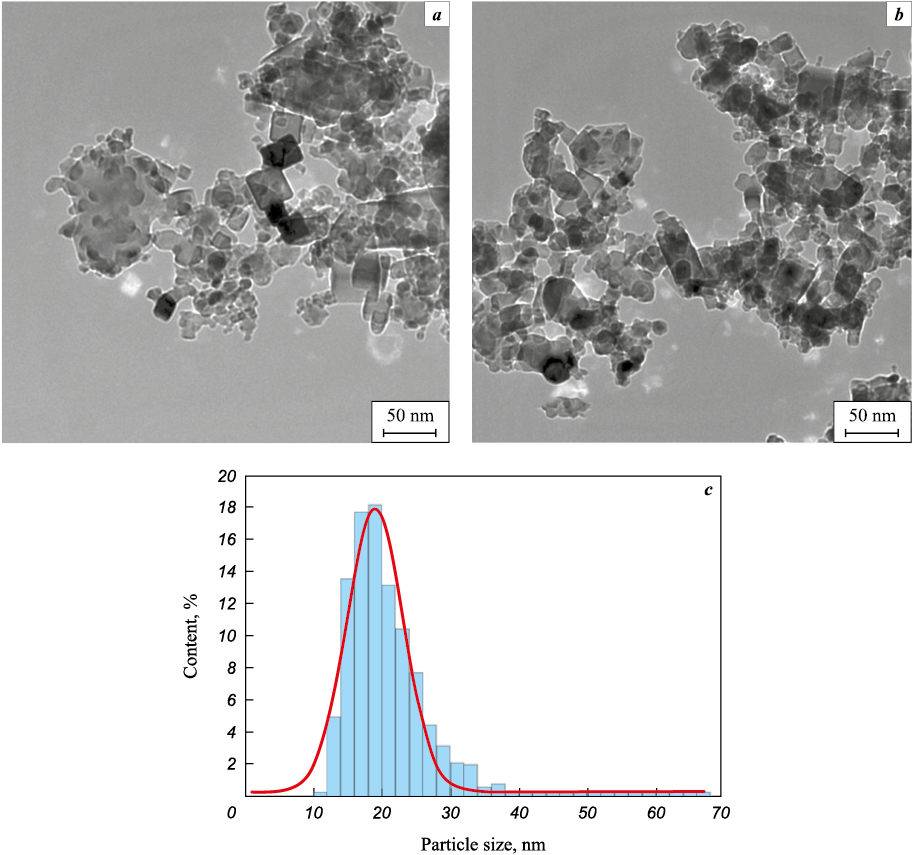

Visualization of the core–shell structure using the example of a nanocrystalline fraction from classifier 2 – a bag-type fabric filter – was confirmed by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. HR TEM of a nanocrystalline powder with a core–shell structure obtained from a powder |

Figure 2, a, b shows the general picture, which demonstrates that the fraction from the filter is really nanodispersed, since the average particle size based on the results of 767 measurements is 18.9 ± 0.2 nm; the histogram of particle size distribution is shown in Fig. 2, c.

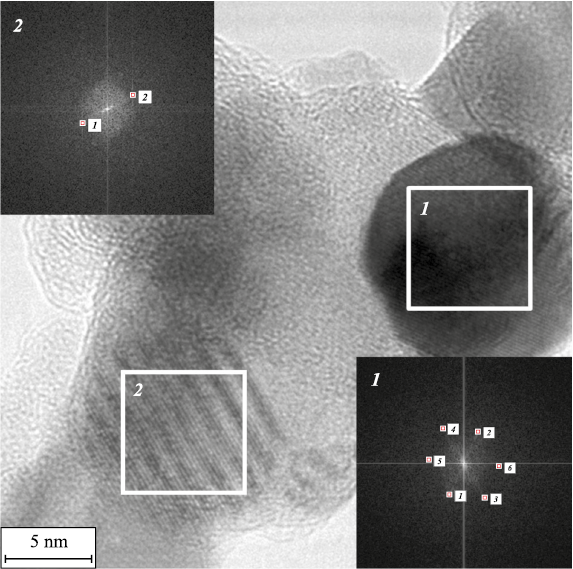

The presence of a core–shell structure is determined by the presence of high-contrast areas at the periphery of the grains, and the grains themselves have both a round and faceted shape, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. HR TEM of nanocrystalline powder particles with a core–shell structure |

Figure 3 shows the results of fixation of metallic nickel (plot 1) and titanium carbide TiC (plot 2). According to the results of measurements of interplanar spacing in plot 1, cubic metallic Ni (Fm-3m space group) is characterized by interplanar spacings d200 = 0.1797 nm, d111 = 0.2054 nm, and d–111 = 0.2087 nm. In plot 2, the identified planes belong to TiC (Fm-3m space group), d111 = 0.2533 nm.

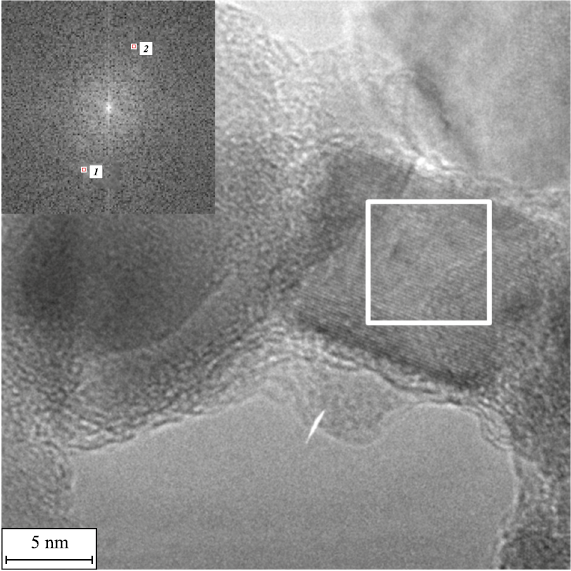

The hexagonal Ni is present in the form of a (002) plane with interplanar spacing d002 = 0.2189 nm in the section of the electron microscope image shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Localized state of hexagonal metallic Ni according to the results of HR TEM |

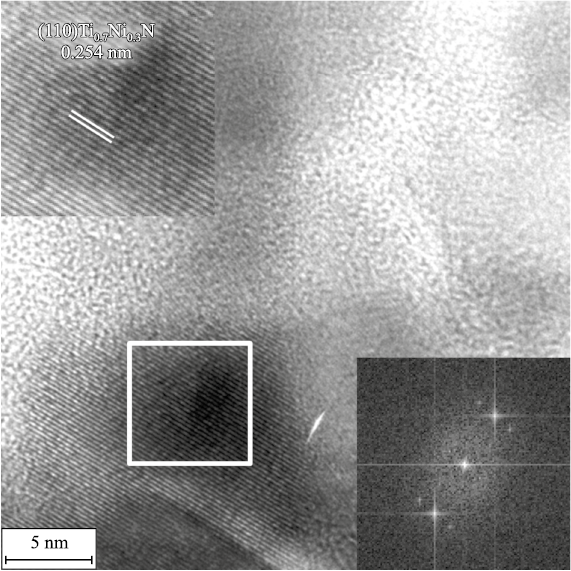

The presence of titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N of the hexagonal modification (P-6m2 space group, d100 = 0.2543 nm) along with hexagonal Ni (space group P63/mmc, d100 = 0.2250 nm) and cubic TiC (Fm-3m space group, d111 = 0.2568 nm) is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Localized state of Ti0.7Ni0.3N (P-6m2 space group) according to the results of HR TEM |

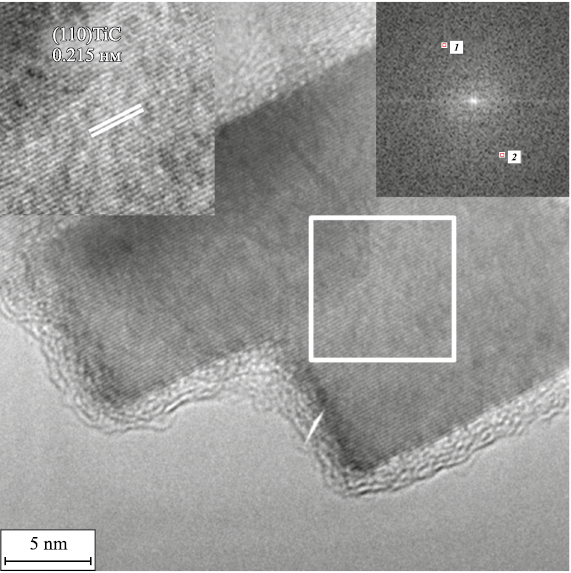

Based on the TEM studies, Fig. 6 shows an example of the presence of faceted particles of cubic titanium carbide TiC – the composition of the presented faceted particle is interpreted by the (200) TiC plane (Fm-3m space group), d200 = 0.2150 nm.

Fig. 6. Faceted nanocrystalline TiC particle coated with an amorphous layer of metallic nickel |

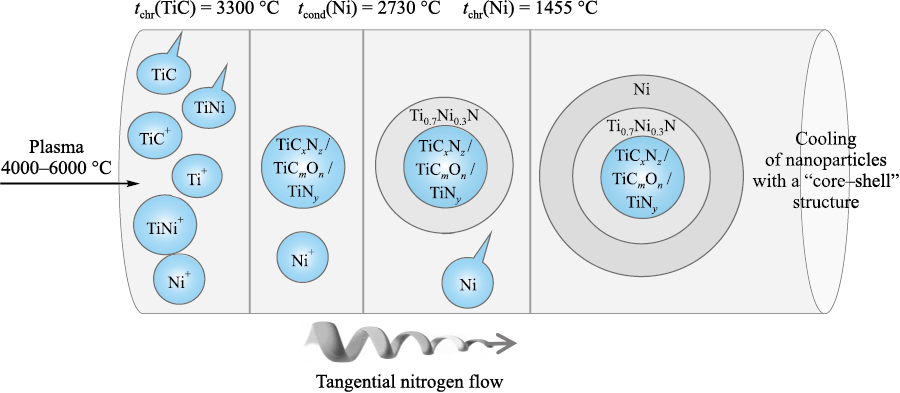

Summarizing the findings of X-ray diffraction and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, we can formulate a chemical model of the core–shell structures formed during plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma followed by crystallization in an intensely swirling nitrogen flow (Fig. 7). The model is based on the physicochemical properties of all interpreted phase components, which include boiling, condensation and crystallization temperatures [22; 23], as well as functional dependences ΔG(t) under equilibrium conditions [24]. Additionally, information on the wettability of refractory compounds [22] by molten nickel metal was utilized to justify the metallic shell on the periphery of nanocrystalline refractory particles.

Fig. 7. Chemical mechanism of formation of a core–shell structure during plasma-chemical synthesis |

Within the framework of this model, the flow of low-temperature plasma with a mechanical mixture of TiC and TiNi is separated by temperature barriers as it enters the quenching chamber filled with nitrogen. The boiling or crystallization temperatures of all phase components determined by X-ray diffraction are selected as temperature barriers.

Keeping in mind that low-temperature plasma can exist only in the temperature range of 4000–6000 °C, the first temperature barrier responsible for the crystallization of the refractory components of the emerging core–shell structures can be identified as the transition of titanium carbide from a gaseous state to a solid state described in [25–28], its temperature is 4300 °C [23]. Considering the significant excess of gaseous nitrogen in the entire volume of the quenching chamber, it can be stated that under these conditions it interacts with solid-phase TiC with the subsequent formation of carbonitride TiCxNz (see the Table). The functional dependences ΔG(t) for these processes [24] and the data on phase formation in the Ti–C–N system [29] confirm that mutual solid solutions with wide homogeneity regions can be formed. At the same time, during the crystallization of refractory components in the quenching chamber, TiNy titanium nitride nanoparticles, isomorphic to Ti–C–N compounds, can be formed on the surface.

Separately, it should be mentioned that passing the temperature range of 4300–3930 °C nickel remains in a gaseous state up to the temperature of 2730 °C [30], at which it passes from a gaseous to a liquid state and which is the second temperature barrier. Passing the boiling point, liquid nickel actively interacts with refractory grains. Under these conditions, titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N is formed [21] according to the theory of heterogeneous nucleation by B. Chalmers [31], some provisions of which are given in [8] by the reaction equation

| TiNy (s) + Ni (l) + N2↑ → Ti0.7Ni0.3N. | (1) |

It should be noted that the complex nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N and its analogue Ti0.7Co0.3N were earlier detected by X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy and described in [21; 32–34].

Reaction (1) occurs in the temperature range from 1600 °C [18] to 1455 °C, which corresponds to the crystallization temperature of metallic nickel and constitutes the third temperature barrier in the presented model. As nickel crystallizes, no chemical interactions occur in the formed core–shell structures, and all the resulting compositions can only cool down at this stage. Next, the mixture of processed fractions is transported to classifiers 1 and 2 for separation.

Conclusion

As a result of plasma-chemical synthesis in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma, we obtained ultrafine and nanocrystalline fractions of particles with a core–shell structure from a mechanical mixture of titanium carbide TiC and titanium nickelide TiNi in the ratio of 1:1.

All the resulting powder compositions were studied by X-ray diffraction and helium pycnometry. The specific surface area was determined using the BET method. The nanocrystalline fraction was thoroughly investigated using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy.

Based on the research findings, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1. The ultra- and nanodispersed compositions formed during plasma-chemical synthesis have a core–shell structure. According to X-ray phase analysis confirmed by the results of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, the refractory core is the TiC/TiCxNy /TiCxOz compound coated with a metallic Ni shell; the complex titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N acts as an interphase layer.

2. Based on X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy data, taking into account the physicochemical features of the detected phase components, we formulated the chemical mechanism for the formation of ultradisperse and nanocrystalline particles with a core–shell structure under crystallization conditions at a rate of 105 °C/s in a tangential nitrogen flow in a quenching chamber of the plasmatron.

3. The chemical mechanism of the formation of nanocrystalline particles is the overcoming of temperature barriers by the plasma flow, with elements evaporated in it that are a part of the charge. The crystallization temperatures of phase components that are present, according to X-ray diffraction, in ultradisperse and nanocrystalline particles act as temperature barriers.

References

1. Song M., Yang Y., Xiang M., Zhu Q., Zhao H. Synthesis of nano-sized TiC powders by designing chemical vapor deposition system in a fluidized bed reactor. Powder Technology. 2021;380:256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2020.11.045

2. Dorosheva I.B., Vokhmintsev A.S., Weinstein I.A., Rempel A.A. Induced surface photovoltage in TiO2 sol-gel nanoparticles. Nanosystems: Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics. 2023;14(4):447–453. https://doi.org/10.17586/2220-8054-2023-14-4-447-453

3. Kozlova T.O., Popov A.L., Romanov M.V., Savintseva I.V., Vasilyeva D.N., Baranchikov A.E., Ivanov V.K. Ceric phosphates and nanocrystalline ceria: selective toxicity to melanoma cells. Nanosystems: Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics. 2023;14(2):223–230. https://doi.org/10.17586/2220-8054-2023-14-2-223-230

4. Balestrat M., Cheype M., Gervais C., Deschanels X., Bernard S. Advanced nanocomposite materials made of TiC nanocrystals in situ immobilized in SiC foams with boosted spectral selectivity. Materials Advances. 2023;(4): 1161–1170.https://doi.org/10.1039/D2MA00886F

5. Kapusta K., Drygas M., Janik J.F., Olejniczak Z. New synthesis route to kesterite Cu2ZnSnS4 semiconductor nanocrystalline powders utilizing copper alloys and a high energy ball milling-assisted process. Journal of Materials Research and Technology. 2020;9(6):13320–13331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.09.062

6. Storozhenko P.A., Guseinov Sh.L., Malashin S.I. Nanodispersed powders: Synthesis methods and practical applications. Nanotechnologies in Russia. 2009;4:262–274. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1995078009050024

7. Tsvetkov Yu.V. Plasma metallurgy: current state, problems and prospects. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 1999;71(10): 1853–1862. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199971101853

8. Zhukov M.F., Cherskiy I.N., Cherepanov A.N., Konovalov N.A., Saburov V.P., Pavlenko N.A., Galevskiy G.V., Andrianova O.A., Krushenko G.G. Hardening of metallic polymeric and elastomer materials by ultrafine powders of plasma-chemical synthesis. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1999. 307 p. (In Russ.).

9. Ermakov A.N., Luzhkova I.V., Avdeeva Yu.A., Dyakov A.A., Maurin N.I. Steel modification method: Patent 2781940 (RF). 2022. (In Russ.).

10. Ermakov A.N., Luzhkova I.V., Avdeeva Yu.A. Steel modification method: Patent 2781935 (RF). 2022. (In Russ.).

11. Pastor H. Titanium-carbonitride-based hard alloys for cutting tools. Materials Science and Engineering: A. 1988.105–106:401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5416(88)90724-0

12. Askarova L.Kh., Grigorov I.G., Zainulin Yu.G. Liquid-phase interaction in the TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Ti system. Metally. 1998;(2):20–24. (In Russ.).

13. Askarova L.Kh., Shchipachev E.V., Ermakov A.N., Grigorov I.G., Zainulin Yu.G. Influence of vanadium and niobium on the phase composition of cermets based on carbide-titanium nitride with a titanium-nickel bond. Neorganicheskie Materialy. 2001;37(2):207–210. (In Russ.).

14. Askarova L.Kh., Grigorov I.G., Fedorenko V.V., Zainulin Yu.G. Liquid-phase interaction in TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Ti–Zr and TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Ti–Zr alloys. Metally. 1998;(5): 16–19. (In Russ.).

15. Askarova L.Kh., Grigorov I.G., Zainulin Yu.G. Liquid-phase interaction in TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Mo and TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Ti–Mo alloys. Metally. 1998;(6):24–27. (In Russ.).

16. Askarova L.Kh., Grigorov I.G., Zainulin Yu.G. Features of phase and structure formation during liquid-phase sintering of TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Nb and TiC0.5N0.5–TiNi–Ti–Nb alloys. Metally. 2000;(1):130–133. (In Russ.).

17. Sadovnikov S.I., Gusev A.I. Effect of particle size and specific surface area on the determination of the density of nanocrystalline silver sulfide Ag2S powders. Physics of the Solid State. 2018;60:877–881. https://doi.org/10.1134/S106378341805027X

18. Bhaskar U.K., Pradhan S.K. Microstructural evolution of nanostructured Ti0.7Ni0.3N prepared by reactive ball-milling. Materials Research Bulletin. 2013;48:3129–3135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2013.04.061

19. Bunaciu A.A., Udriştioiu E.G., Aboul-Enein H.Y. X-ray diffraction: Instrumentation and applications. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry. 2015;45(4):289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2014.949616

20. Fultz B., Howe J.M. Transmission electron microscopy and diffractometry of materials, 3rd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2008. 758 р. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73886-2

21. Ermakov A.N., Luzhkova I.V., Avdeeva Yu.A., Murzakaev A.M., Zainulin Yu.G., Dobrinsky E.K. Formation of complex titanium-nickel nitride Ti0.7Ni0.3N in the “core-shell” structure of TiN–Ni. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2019.84:104996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2019.104996

22. Mhadhbi M., Driss M. Titanium carbide: Synthesis, properties and applications. Brilliant Engineering. 2021;2:1–11. https://doi.org/10.36937/ben.2021.002.001

23. Banaszek K., Klimek L. Wettability and surface free energy of Ti(C,N) coatings on nickel-based casting prosthetic alloys. Archives of Foundary Engienering. 2015;15:11–16. https://doi.org/10.1515/afe-2015-0050

24. Barin I. Thermochemical data of pure substances. 3rd ed. Weinheim, New York, Base1, Cambridge, Tokyo: VCH, 1995. 2003 с.

25. Gusev A.I., Rempel A.A. Nonstoichiometry, disorder and order in a solid. Ekaterinburg: NISO UrO RAN, 2001. 579 p. (In Russ.).

26. Samokhin A.V., Polyakov S., Astashov A.G., Tsvetkov Yu.V. Simulation of the process of synthesis of nanopowders in a plasma reactor jet type. I. Statement of the problem and model validation. Fizika i Khimiya Obrabotki Materialov. 2013;(6):40–46. (In Russ.).

27. Samokhin A.V., Polyakov S.N., Astashov A.G., Tsvetkov Yu.V. Simulation of the process of nanopowder synthesis in a jet-type plasma reactor. II. Nanoparticles formation. Inorganic Materials: Applied Research. 2014;5(3):224–229. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2075113314030149

28. Shiryaeva L.S. Gorbuzova A.K., Galevsky G.V. Production and application of titanium carbide (assessment, trends, forecasts). Nauchno-tekhnicheskie vedomosti Sankt-Peterburgskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. 2014;2(195):100–107. (In Russ.).

29. Binder S., Lengauer W., Ettmayer P., Bauer J., Debuigne J., Bohn M. Phase equilibria in the systems Ti–C–N, Zr–C–N and Hf–C–N. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 1995;217(1):128–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0925-8388(94)01314-8

30. Moghimi Z.A., Halali M., Nusheh M. An investigation on the temperature and stability behavior in the levitation melting of nickel. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B. 2006;37B:997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02735022

31. Filkov M., Kolesnikov A. Plasmachemical synthesis of nanopowders in the system Ti(O,C,N) for material structure modification. Journal of Nanoscience. 2016;2016: 1361436. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1361436

32. Avdeeva Yu.A., Luzhkova I.V., Ermakov A.N. Mechanism of formation of nanocrystalline particles with core-shell structure based on titanium oxynitrides with nickel in the process of plasma-chemical synthesis of TiNi in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma. Nanosystems: Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics. 2022;13(2):212–219. https://doi.org/10.17586/2220-8054-2022-13-2-212-219

33. Avdeeva Yu.A., Luzhkova I.V., Ermakov A.N. Formation of titanium-cobalt nitride Ti0.7Co0.3N under plasma-chemical synthesis conditions in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma. Nanosystems: Physics, Chemistry, Mathematics. 2021;12(5):641–649. https://doi.org/10.17586/2220-8054-2021-12-5-641-649

34. Avdeeva Yu.A., Luzhkova I.V., Ermakov A.N. Plasmachemical synthesis of TiC–Mo–Co nanoparticles with a core–shell structure in a low-temperature nitrogen plasma. Russian Metallurgy. 2022;(9):1019–1026. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0036029522090038

About the Authors

Yu. A. AvdeevaRussian Federation

Yuliya A. Avdeeva – Research Scientist

91 Pervomaiskaya Str., Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Region 620990, Russia

I. V. Luzhkova

Russian Federation

Irina V. Luzhkova – Research Scientist

91 Pervomaiskaya Str., Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Region 620990, Russia

A. M. Murzakaev

Russian Federation

Aidar M. Murzakaev – Cand. Sci. (Phys.-Math.), Senior Researcher

106 Amundsen Str., Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Region 620216, Russia

A. N. Ermakov

Russian Federation

Alexey N. Ermakov – Cand. Sci. (Chem.), Senior Researcher

91 Pervomaiskaya Str., Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Region 620990, Russia

Review

For citations:

Avdeeva Yu.A., Luzhkova I.V., Murzakaev A.M., Ermakov A.N. Plasma-chemical synthesis of highly dispersed core–shell structures from a mechanical mixture of titanium carbide and titanium nickelide. Powder Metallurgy аnd Functional Coatings (Izvestiya Vuzov. Poroshkovaya Metallurgiya i Funktsional'nye Pokrytiya). 2024;18(3):5-15. https://doi.org/10.17073/1997-308X-2024-3-5-15